Arctic voyage finds global warming impact on ice, animals

The email arrived in mid-June, seeking to explode any notion that global warming might turn our Arctic expedition into a summer cruise.

“The most important piece of clothing to pack is good, sturdy and warm boots. There is going to be snow and ice on the deck of the icebreaker,” it read. “Quality boots are key.”

The Associated Press was joining international researchers on a month-long, 10,000 kilometer (6,200-mile) journey to document the impact of climate change on the forbidding ice and frigid waters of the Far North. But once the ship entered the fabled Northwest Passage between the Atlantic and the Pacific, there would be nowhere to stop for supplies, no port to shelter in and no help for hundreds of miles if things went wrong. A change in the weather might cause the mercury to drop suddenly or push the polar pack into the Canadian Archipelago, creating a sea of rock-hard ice.

So as we packed our bags, in went the heavy jackets, insulated trousers, hats, mittens, woolen sweaters and the heavy, fur-lined boots.

Global warming or not, it was best to come prepared.

If parts of the planet are becoming like a furnace because of global warming, then the Arctic is best described as the world’s air-conditioning unit. The frozen north plays a crucial role in cooling the rest of the planet while reflecting some of the sun’s heat back into space.

Yet for several decades, satellite pictures have shown a dramatic decline in Arctic sea ice that is already affecting the lives of humans and animals in the region, from Inuit communities to polar bears. Experts predict that the impact of melting sea ice will be felt across the northern hemisphere, altering ocean currents and causing freak weather as far south as Florida or France.

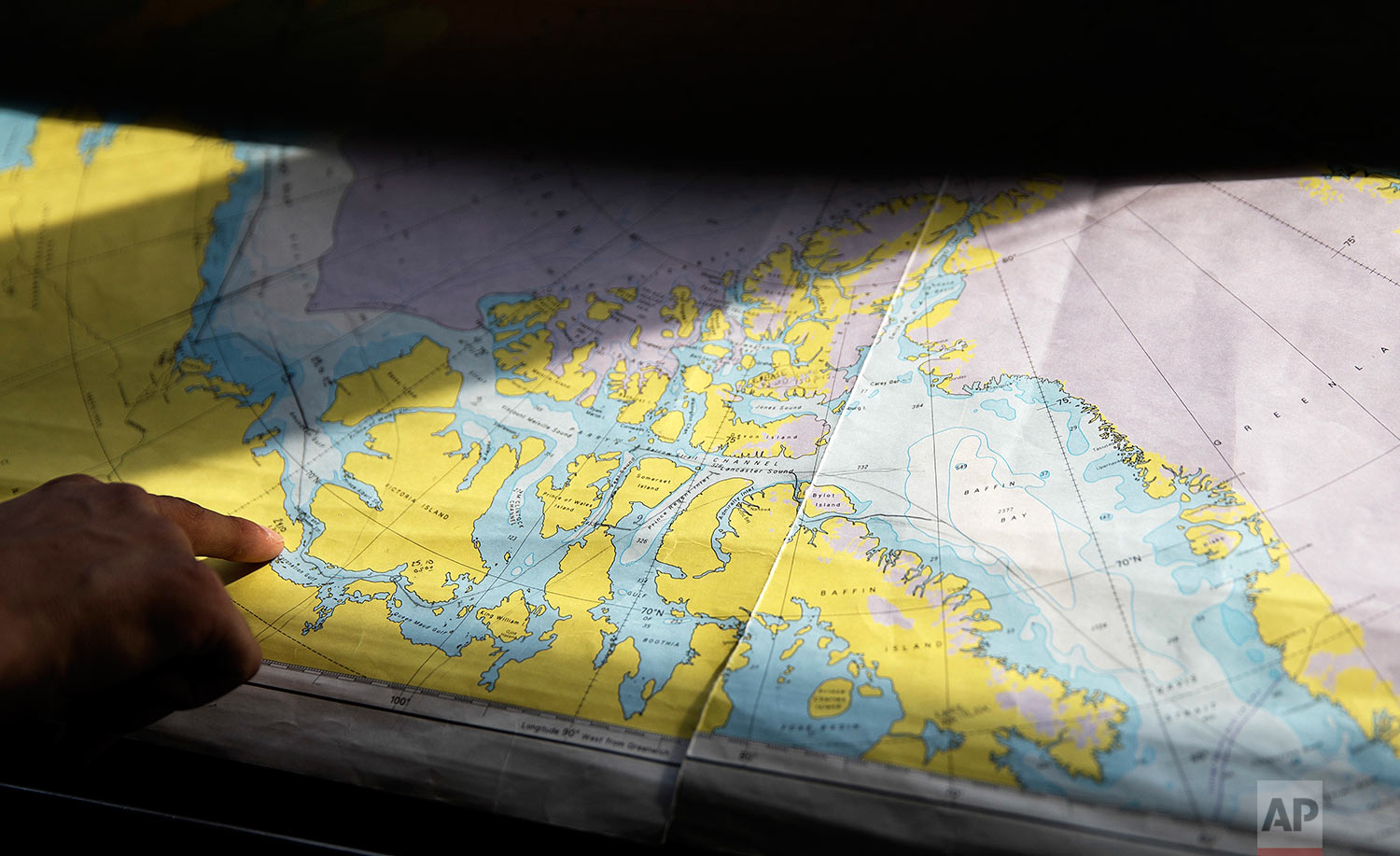

“Things are changing in the Arctic, and that is changing things everywhere else,” said David ‘Duke’ Snider, the seasoned mariner responsible for navigating the Finnish icebreaker MSV Nordica through the Northwest Passage last month.

Researchers on the trip sought a first-hand view of the effects of global warming already seen from space. Even the dates of the journey were a clue: The ship departed Vancouver in early July and arrived in Nuuk, Greenland on July 29th, the earliest transit ever of a region that isn’t usually navigable until later in the year.

As it made its way through the North Pacific — passing Chinese cargo ships, Alaskan fishing boats and the occasional far-off whale — members of the expedition soaked up the sun in anticipation of freezing weeks to come.

Twelve days after the ship had left Vancouver, the ice appeared out of nowhere.

At first, lone floes bobbed on the waves like mangled lumps of Styrofoam. By the time Nordica reached Point Barrow, on Alaska’s northernmost tip, the sea was swarming with ice.

Snider recalled that when he started guiding ships through Arctic waters more than 30 years ago, the ice pack in mid-July would have stretched 50 miles farther southwest. Back then, a ship also would have encountered much thicker, blueish ice that had survived several summer melts, becoming hard as concrete in the process, he said.

He likened this year’s ice to a sea of porridge with a few hard chunks — no match for the nimble 13,000-ton Nordica.

Since the first orbital images were taken in 1979, Arctic sea ice coverage during the summer has dropped by an average of about 34,000 square miles each year — almost the surface area of Maine or the country of Serbia. More recent data show that not only is its surface area shrinking, but the ice that’s left is getting thinner too. Snider said he has seen the ice cover reduced in both concentration and thickness.

The melting ice is one reason why modern ships have an easier time going through the Northwest Passage, 111 years after Norwegian adventurer Roald Amundsen achieved the first transit. Early explorers found themselves blinded by harsh sunlight reflecting off a desert of white, confused by mirages that give the illusion of giant ice cliffs all around, and thrown off course by the proximity of the North Pole distorting their compass readings.

Modern mariners can get daily satellite snapshots of the ice and precise GPS locations that help them dodge dangerous shallows. But technology can be fickle. After two weeks at sea the ship’s fragile Internet connection went down for six days: no emails, no Google, no new satellite pictures to preview the route ahead.

The outdoor thermometer indicated a temperature of 47 degrees Fahrenheit (8.3 Celsius), but in the never-setting sun of an Arctic summer it felt more like 60 F. Days blurred into nights. Distant smoke from Cape Bathurst signaled slow-burning shale fires, while giant white golf balls indicated the remains of Cold War radar stations.

At one point a row of shacks appeared on a hill. As the ship passed by Cambridge Bay — home to Canada’s High Arctic Research Station— a brief cellphone signal flickered to life, allowing one homesick sailor to make a tearful call to his family.

The Finnish crew, meanwhile, took solace in the creature comforts of home, such as the on-board sauna and reindeer roast on Saturdays.

Even in their bunks, those on board heard the constant churning of ice as the ship plowed through the debris rolling beneath the hull, thundering like hail on a tin roof.

___

As the icebreaker entered Victoria Strait, deep inside the Northwest Passage, we looked for a shadow moving in the distance or a flash of pale yellow in the expanse of white that would signal the presence of the world’s largest land predator.

At last, a cry went out: “Nanuq, nanuq!”

Maatiusi Manning, an Inuit sailor, had spotted what everyone on board was hoping to see — the first polar bear.

A polar bear walks away after feasting on the carcass of a seal on the ice in the Franklin Strait.

The 1,000-pound predators are at the top of a food chain that’s being pummeled by global warming because of the immediate impact vanishing sea ice has on a range of animals and plants that depend on it.

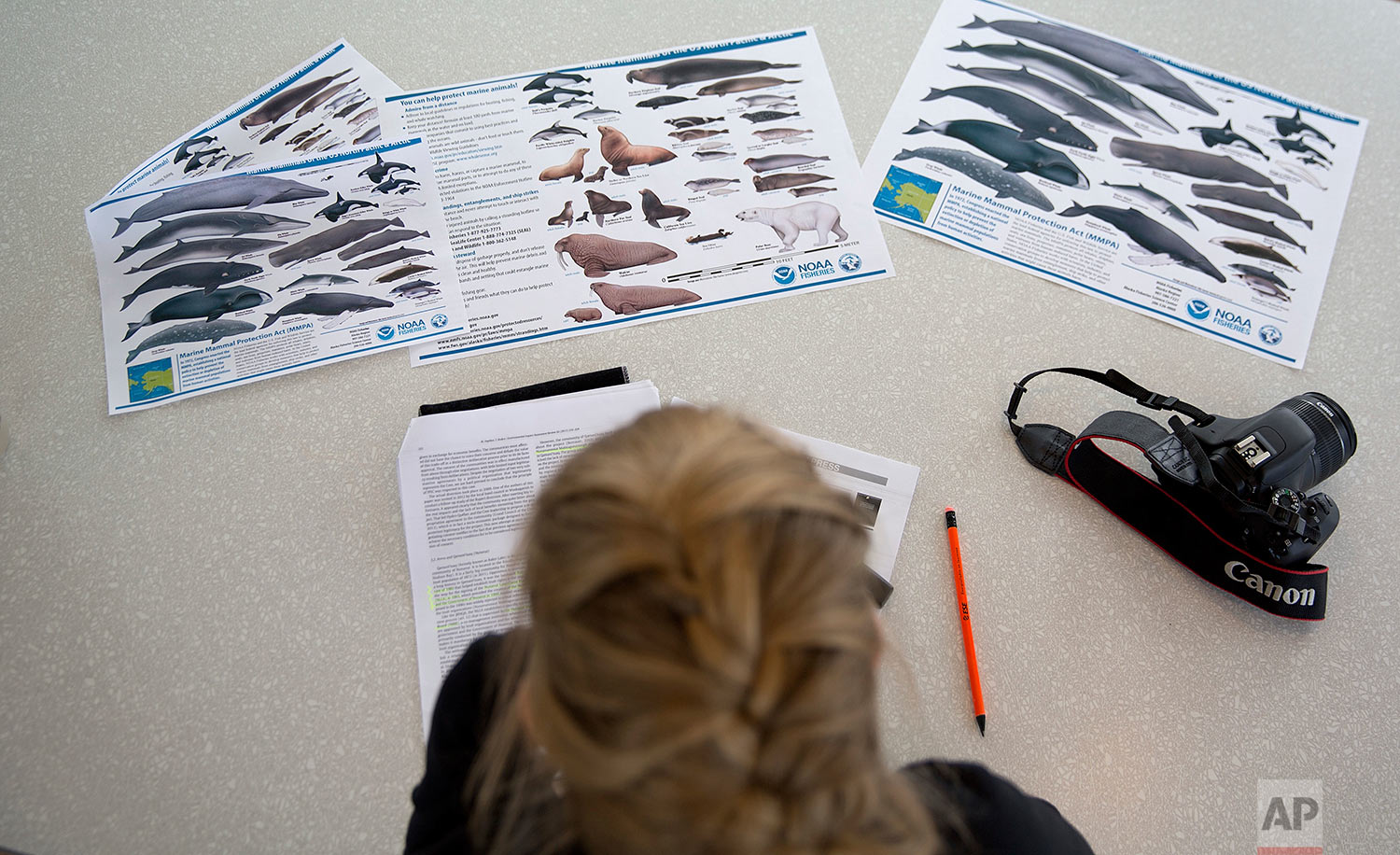

“If we continue losing ice, we’re going to lose species with it,” said Paula von Weller, a field biologist who was on the trip.

No Arctic creatures have become more associated with climate change than polar bears. The U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service estimated in January that about 26,000 specimens remain in the wild. Population counts of polar bears are notoriously difficult, and researchers are unsure how much their numbers have changed in recent years. But the Fish and Wildlife Service warned that melting sea ice is robbing the bear of its natural hunting ground for seals and other prey.

While some polar bears are expected to follow the retreating ice northward, others will head south, where they will come into greater contact with humans — encounters that are unlikely to end well for the bears.

Still, being the poster child of Arctic wildlife may help the polar bear. Sightings are a highlight for adventure tourists who are flocking to Arctic cruises in increasing numbers.

Last year, the hottest on record in the Arctic, the Crystal Serenity took 1,100 high-paying guests on a cruise of the Northwest Passage, prompting environmentalists to warn of an Arctic tourism rush that could disrupt wildlife habitat. Crystal Cruises says it works closely with local guides, marine biologists and conservationists to ensure wildlife isn’t harmed.

A path in the ice is left in the wake of the Finnish icebreaker MSV Nordica.

Von Weller said there are benefits to people seeing the region and its animals themselves.

“People are so far removed from the Arctic that they don’t understand it, they don’t know it and they don’t love it,” she said. “I think it’s important for people to see what’s here and to fall in love with it and have a bond and want to protect it.”

That love may need to extend further down the food chain if the fragile ecosystem in the Arctic continues to fall apart. Some of the animals highly associated with the ice are not going to be able to adapt in a reasonable amount of time to keep up with climate change, Weller said.

“The walrus, for example, may spend more time on the mainland. They’re very prone to disturbance so that’s not a good place for walrus to be,” said von Weller.

Research published four years ago rang alarms bells about the future of the red king crab — a big earner for Alaska’s fishing industry — because rising levels of carbon dioxide, a driver of global warming, are making oceans more acidic. Scientists found that juvenile crabs exposed to levels of acidification predicted for the future grew more slowly and were more likely to die.

Algae that cling to the underside of sea ice are also losing their habitat. If they vanish, the impact will be felt all the way up the food chain. Copepods, a type of zooplankton that eats algae, will lose their source of food. The tiny crustaceans in turn are prey for fish, whales and birds.

Meanwhile, new rivals from the south are already arriving in the Arctic as waters warm. Orca have been observed traveling further north in search of food in recent years, and some wildlife experts predict they will become the main seal predator in the coming decades, replacing polar bears.

Humans are also increasingly venturing into the Arctic in search of untapped deposits of minerals and fossil fuels — posing a threat to animals. The potential for oil spills from platforms and tankers operating in remote locations has been a major cause for concern among environmentalists since the 1989 Exxon Valdez disaster off Alaska killed a quarter of a million seabirds, as well as hundreds of seals and sea otters. Simply getting the necessary emergency response ships to an Arctic spill would be a challenge, while cleaning oil off sea ice would likely take months.

Last month, Canada’s supreme court ruled in favor of the Clyde River community of Baffin Island, which is fighting the proposed seismic blasts used by oil companies to map the sea floor. The Inuit fear that the loud underwater noise caused by the blasts could disorient marine mammals such as whales that depend on sound to communicate, and affect the reproductive cycles of fish and shrimp stocks.

The Inuit and other local peoples are already feeling the impact of global warming because they rely on frozen waterways to reach hunting grounds or relatives on other islands. But some say it will not be all bad: Cruise ships offer potential revenue to those Inuit communities willing to engage with tourists.

The absence of sea ice for longer periods each summer, meanwhile, will allow boats to supply villages and mines for longer periods of the year. Where it used to be a hard and fast rule that ships had to be out of the Northwest Passage by Sept. 28, the operating season now stretches beyond October.

Tiina Jaaskelainen, a researcher at the Hanken School of Economics in Finland who was on board the icebreaker, said responding to these changes will require a better understanding of the social impact rather than just the science of climate change.

“Inuit communities need to be involved in planning each use of the passage and the Arctic in general,” she said. “It’s important they can play an active role in the region’s economic development, while good governance may enable local communities to also maintain their traditions.”

___

Upon entering the Atlantic, the FM radios aboard Nordica began picking up local stations again, including one that played David Bowie’s ‘Ziggy Stardust.’ Nordica reached Nuuk, the capital of Greenland, after 24 days.

“The fact that we were able to plan and execute this transit so efficiently says something about the changes in the ice,” said Scott Joblin, an expert on maritime and polar law from Australian National University in Canberra who studies the legal implications of climate change in the Arctic.

Scientists believe there is no way to reverse the decline in Arctic sea ice in the foreseeable future. Even in the best-case scenario envisaged by the 2015 Paris climate accord, sea ice will largely vanish from the Arctic during the summer within the coming decades.

In the end, the route that foiled countless explorers claimed little more than a camera and a drone.

But we did get a taste of the warming Arctic: Those heavy fur-lined boots never got used.

Text from the AP news story, Arctic voyage finds global warming impact on ice, animals, by Frank Jordans.

Photos by David Goldman

Learn more about the Arctic and read dispatches sent by a team of AP journalists as they traveled through the region’s fabled Northwest Passage last month: https://www.apnews.com/tag/NewArctic

Visual artist and Journalist