Peru’s shoestring circuses struggle to survive

Inside a yellow and blue tent overlooking the desert hills of Peru’s capital city, the Tony Perejil circus comes to life.

A set of brown goats hobble up a narrow plank. A woman balances a newspaper rolled into an inverted cone on her nose. Another performer does acrobatics on horseback before half-empty rows of spectators.

The mom-and-pop style spectacle is one of about a hundred remaining circuses in Peru that manage to eke out a living despite waning public enthusiasm for clown and animal acts in an age of viral internet videos and cellphones.

Homes in the Puente Piedra shantytown light up the landscape surrounding the Tony Perejil circus on the outskirts of Lima, Peru. (AP Photo/Martin Mejia)

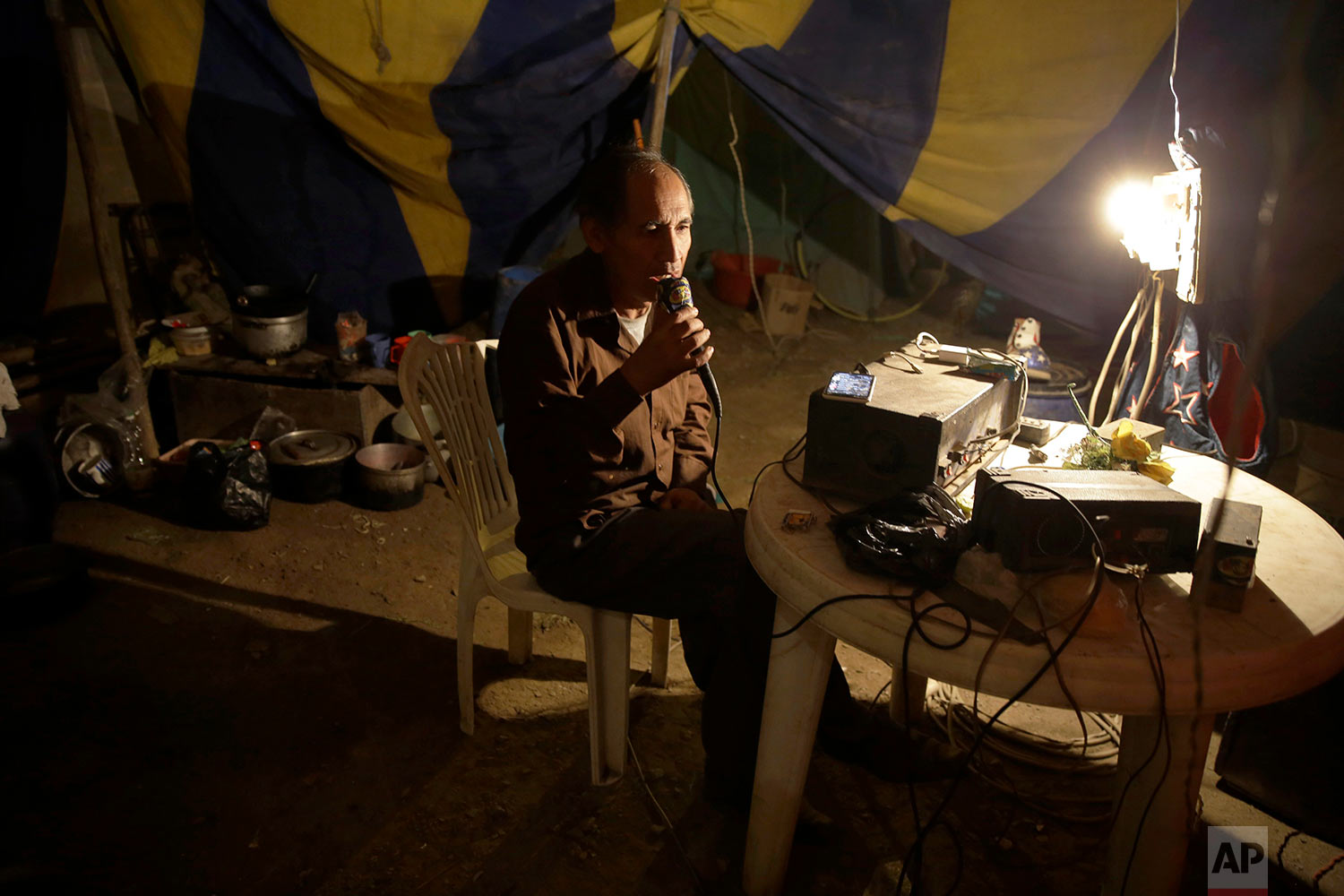

On a recent night, Jose Alvarez tallied the ticket sales for the circus named after his father and sighed when he realized they’d earned less than $40.

“Lima is lousy,” the 52-year-old businessman said, adding he’d move his circus north toward Peru’s border with Ecuador in search of a brighter future.

These days, Lima’s circus acts find themselves increasingly pinched for space and money.

Urban expansion in the city of 10 million inhabitants has made it tough to find enough space to set up a tent in a centrally located neighborhood. Gangs of delinquents charge up to $10 a day for circuses to set up shop in depressed barrios. And a 2011 law prohibits them from using wild animals in their shows.

“Any available space is sold to malls,” lamented Alvarez, who also performs as a clown. “No one thinks about the circus.”

Alvarez remembers happier times in the 1980s, when his father filled their circus tent with people even though Peru was in the midst of an economic crisis and a war raged between the state and Sendero Luminoso guerrillas.

“The circuses were never affected,” he said.

His family’s circus today still maintains much of the old-time traditions of the past: Clowns use makeup to inflate the appearance of their lips, make jokes and don goofy, oversized overalls. A woman in a pink leotard sways from a cord dangling from the ceiling as children watch, mouths agape. The tent has a traditional cone-shaped roof and a simple dirt stage.

Even the profession of clowning has hit hard times, Alvarez said, adding that while some 500 clowns across the country have their own labor association, they have been unable to improve meager wages and living conditions.

“The word ‘clown’ is used incorrectly in Peru,” he said. “It’s understood as a pejorative.”

Text from the AP news story, AP PHOTOS: Peru’s shoestring circuses struggle to survive, by Franklin Briceño.

Photos by Martin Mejia