Peace warriors

At his desk at North Lawndale College Prep High School, Gerald Smith keeps a small calendar that holds unimaginable grief.

In its pages, the dean and student advocate writes the name of each student who's lost a family member, many of them to gun violence. And then he deploys the Peace Warriors — students who have dedicated themselves to easing the violence that pervades their world.

The Warriors seek out their heartbroken classmates. They offer a hug, and a small bag of candy.

Since September, Smith has added more than 160 names to that little book, roughly half the student body at this campus on Chicago's West Side. And that doesn't even include those whose friends have been killed.

"We would run out of candy," says Smith, sadly.

It is hard and often anguishing work, keeping the peace. North Lawndale's Peace Warriors do it in small and large ways. When invited to Parkland, Florida, after 17 people died in a school shooting there in February, they answered the call — to mourn together and to unite in what's become a national youth movement aimed at stopping gun violence.

Weeks later, Alex King and D'Angelo McDade, seniors at North Lawndale, walked onto stage at the March for Our Lives in Washington, D.C. with fists raised. They marveled at the masses of young people who'd joined the fight. Said King: "We knew this was going to be in the history books. And for me, it was like, 'Wow! I'm actually being heard.'"

They continue to press their solution to urban violence: more jobs and investment in low-income communities like theirs. But that's the long game.

First, the Peace Warriors must survive — and help their peers do the same.

___

"Good morning, good morning, good morning!"

A small band of Peace Warriors greets students who make their way into the school's main foyer after going through a bag check and metal detector.

This is when the Warriors get a sense of how the day may go and where they may need to step in to maintain calm.

Most everyone is upbeat, though perhaps a little sleepy. A few dance to old-school soul over the sound system, until a young woman arrives, sobbing. Two Peace Warriors rush to embrace her and escort her to the school office, where she can collect herself.

When the group began in 2009, there were just 17 Peace Warriors on the school's two campuses. Back then, that small corps spent much of its time breaking up fights, "interrupting nonsense," as they call it. Since then, their ranks have grown to more than 120 — and fights have dropped markedly, Smith said.

Now, the Peace Warriors focus more on running "peace circles," mediating verbal altercations between students and tense exchanges on social media.

Alexis Willis is among the newest recruits. Like the others, she had to learn the "Six Principles of Nonviolence" of the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. before she could call herself a Peace Warrior.

The civil rights activist lived in the neighborhood in 1966 in an apartment that was just down the street. He chose that location to draw attention to segregation and extreme poverty — issues that persist there even today.

Willis, a freshman who trained in January, likes King's first principle best: "Nonviolence is a way of life for courageous people."

She admits that, as a child, she sometimes solved problems with her fists. But as the level of violence has escalated in her city, and she has matured, she has been drawn to "this life," as the Peace Warriors sometimes call their pacifist practice.

Willis says her resolve to help her classmates "do better" was only solidified when, in April, her beloved 16-year-old cousin, Jaheim Wilson, was shot and killed as he walked with a friend in an alley near his Chicago home.

"Nobody that's 16 should have to die," Willis says, quietly.

Less than two weeks after her cousin's death, she received her first Peace Warrior shirt with her name and an image of a large hand flashing a peace sign on the back.

"When you put on this shirt, you put on a target. People will test you," Smith tells his students when first handing them their shirts.

Indeed, being a Peace Warrior can be a challenge. Some students call them snitches or see them as meddling do-gooders. In recent years, Smith has had a harder time recruiting young men to join the group, unfortunate since they are most often the victims of violence.

Alex King confesses that he first simply joined the group because he wanted to wear the Peace Warrior shirt to school instead of the otherwise required collared white polo. But he soon came to see the group as family.

Speaking at the March for Our Lives, he shared the story of his nephew, Daishawn Moore, also 16, who was gunned down last May.

"Through my friends and colleagues, I found help to come up out of a dark place," King told the crowd. Full of rage and sorrow, he had planned to retaliate against his nephew's killer, until fellow Peace Warriors talked him out of it: "Everyone doesn't have the same resources or support system as I was lucky to have."

The alliance with Parkland unites the North Lawndale students with those from a very different world — wealthy and suburban, a place where shootings are far from the norm.

While students from Parkland and elsewhere are pushing lawmakers for stricter gun regulations, the Peace Warriors have made poverty their target. Among other things, the Peace Warriors want more funding for mental health clinics and schools in low-income neighborhoods. Both have seen cuts in recent years in Chicago.

At North Lawndale College Prep, a charter school that is privately funded, Smith says there once were four counselors, one for each grade. Now there are only two who serve grades nine through 12.

It means that Smith and other staff — and even the Peace Warriors — must pick up some of the slack.

___

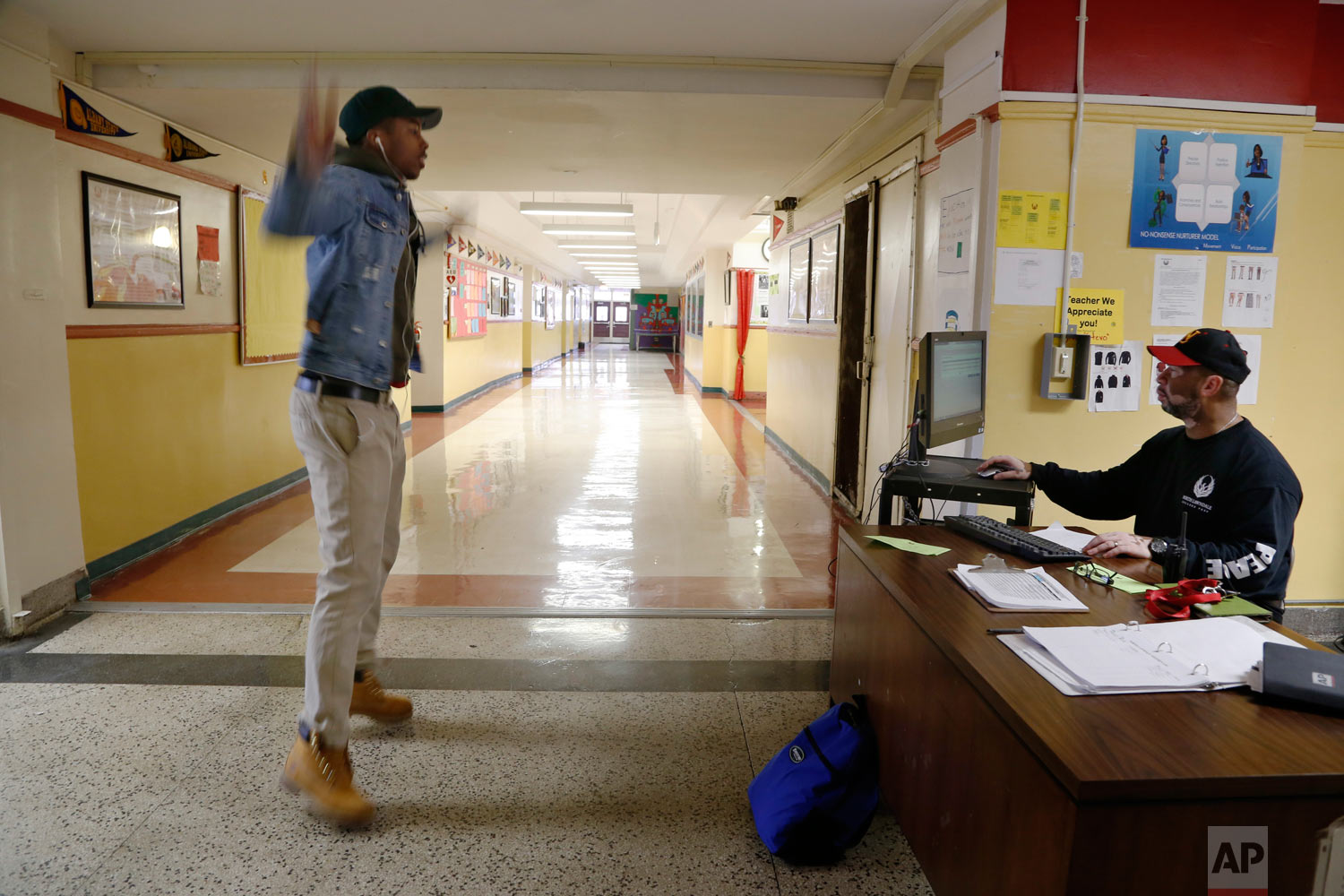

On that recent morning, the girl who'd arrived at school sobbing walks up to the school security desk, where Smith is tracking late arrivals.

He knows why she wasn't in class. Her boyfriend had just been shot and killed. But why, he asks, is she carrying a bundle of clothing?

"It's his clothes," she answers in a monotone before heading down the hallway in a daze.

Smith covers his eyes for a moment, then reveals cheeks wet with tears.

It doesn't matter how many times this happens. He'll never get used to it.

This wasn't work he'd planned to do. The "reluctant" fourth-generation pastor, now 47, ultimately answered the call to work with youth. Now he has a knack, he says, for spotting potential leaders, some of them also reluctant.

A few days later, freshman Robert Cooks sits in the deans' office, awaiting a detention slip.

Above Smith's desk in that office, red letters are stuck to the wall — a message where there used to be a clock. Smith never bothered to replace it after a distressed student knocked it down.

"This is KAIROS Time," the message reads, using a Greek word that refers to a decisive and opportune moment.

Smith sensed that kind of moment when he accompanied the Peace Warriors to Parkland and later to Washington for the march.

This summer — Chicago's worst time for violence — is another, as he and his students plan sessions to train more Peace Warriors in the neighborhood. Students across the country also plan voter registration drives with an eye on the midterm elections in November. But here, safety must come first.

"This summer is critical. Can't wait until next summer. Can't wait until November," Smith says.

As he works in his office, he stops and gazes at Cooks, the dejected freshman, as if he's seeing him with fresh eyes.

Has Cooks ever considered being a Peace Warrior? The teen says he gets in too much trouble.

"Peace Warriors aren't perfect," Smith tells him. "Don't count yourself out. We need some strong young men."

Maybe, just maybe, this is another "kairos." One of those critical moments.

Time will tell.

Martha Irvine is an AP national writer and visual journalist.