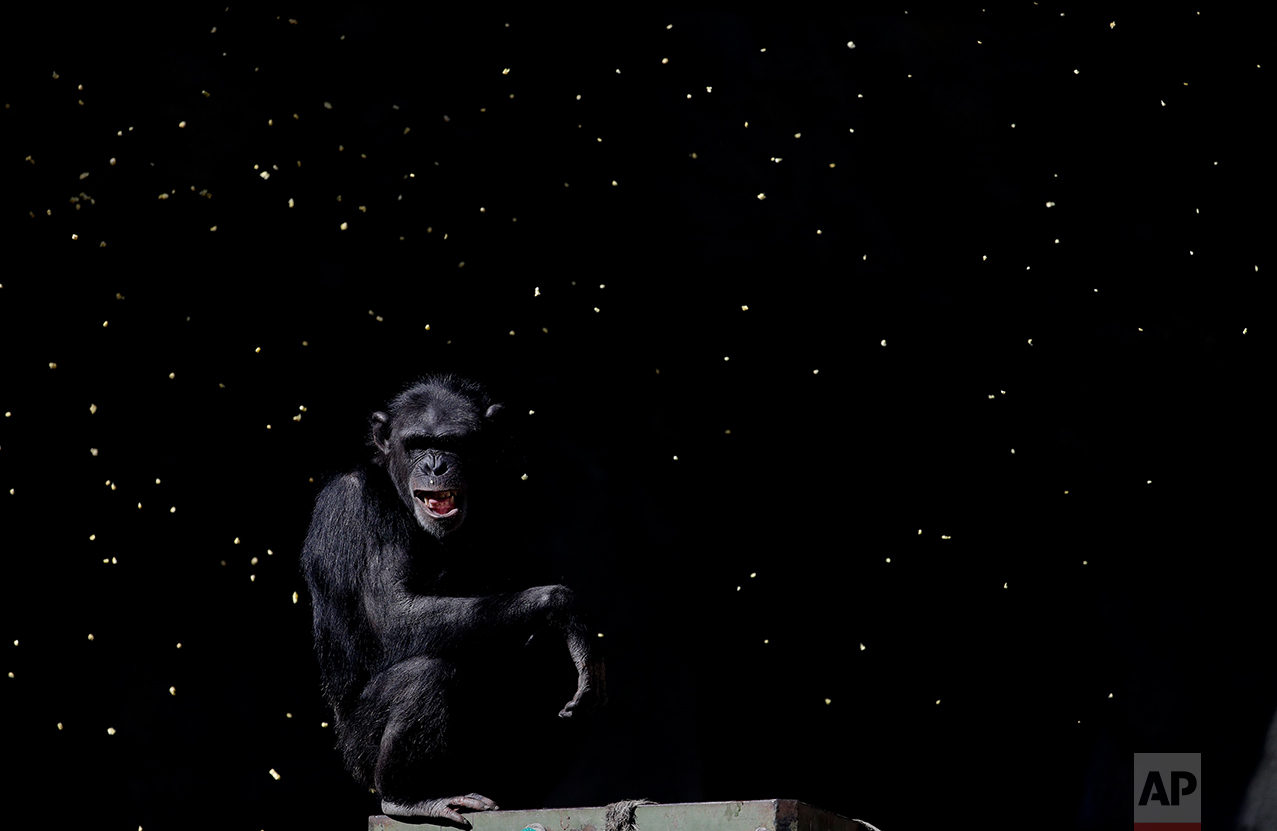

Animals still in cages a year after Buenos Aires zoo closure

The roar of lions, snorts of rhinos and trumpets of elephants still blend with the cacophony of honking buses and screeching cars passing nearby in one of the most heavily congested areas of Argentina’s capital.

A year after the 140-year-old Buenos Aires zoo closed its doors and was transformed into a park, hundreds of animals remain behind bars and in a noisy limbo.

Developers last July promised to relocate most of the zoo’s 1,500 animals to sanctuaries in Argentina and abroad, but they had made no firm arrangements to do so. And a new master plan announced Tuesday still doesn’t specify how they will accomplish it. Many of the animals are so zoo-trained that experts fear they would die if moved, even to wild animal preserves.

Conservationists also complain that the remaining animals still live in antiquated enclosures widely considered inhumane by modern standards — and say the city government’s new plan gives few specifics of how improvements will be made.

“It’s gone from bad to worse,” said Claudio Bertonatti, a former Buenos Aires zoo director and consultant for the Fundacion Azara non-governmental organization. “Everything is set for Noah’s Arc to be shipwrecked.”

The zoo was inaugurated in 1875 on what was then a quiet patch on the outskirts of Buenos Aires but is now an urban zone of busy avenues with bleating buses near the animal cages.

The first director decided that the animals should be housed in buildings that reflected their countries of origin. A replica of a Hindu temple was built for the Asian elephants. Giraffes were housed in an Islamic-inspired structure, the red panda in a Chinese pagoda. Many of those buildings remain on the 45-acre (18-hectare) site, but are in need of repair.

When Mayor Horacio Rodriguez Larreta announced its closure last year, he said the animals were a “treasure” that couldn’t remain in captivity near the noise and pollution.

Since then, some condors have been freed and about 360 other animals rescued from trafficking have been sent to other institutions. But not a single animal owned by the city has been transferred.

City officials say the process has proved more difficult than they thought at first. They found they had closed the zoo before enacting legislation needed to authorize many of the transfers. They only recently hired an official to study which animals can be moved and arrange it. It’s not yet clear how many can stand a move, or who might take them.

The plan being unveiled Tuesday shows a revamped layout and expansion for the park, but critics complain it doesn’t detail plans for the existing animals.

A coalition of a dozen conservationist and veterinarian groups issued an April 28 letter calling on officials to specify which animals will be permanently housed at the park, and in what conditions.

It said the only changes that the master plan makes to the old zoo “are the changing of the name, a rise in the cost of the tickets and the closing of some areas and more staff, without this improving the conditions of the animals.”

Even so, some of the stress for animals has been reduced by a cutback in allowed visitors, who in the past could number 10,000 a day. Only about 2,000 a day are now permitted and some animal habitats are now off-limited.

AP photographer Natacha Pisarenko speaks about her experience on assignment at the Buenos Aires zoo. Video by Paul Byrne | Edited by Dario Lopez-Mills

On a recent morning, Garoto and Porota, a couple of grey hippos swam to edge of their pond and opened their mouths wide showing their caramel teeth while Guille, their baby hippo lurked the dark water.

In a nearby enclosure, the giraffes Shaki, Buddy and their calf, Ciro, stuck out their long tongues to drink water from yellow plastic containers tethered to a roof.

Sandra, the orangutan, was enthralled by some patches of grass that had been recently installed in her enclosure. She became known worldwide when an Argentine court issued a landmark ruling in 2014 that she was entitled to some of the legal rights enjoyed by humans. She’s no longer on display for curious visitors.

“The (city government) hasn’t made the enclosures bigger. There are minor infrastructural changes but there is a total deterioration,” said Juan Carlos Sassaroli, a veterinarian who formerly worked at the zoo.

“The enclosures haven’t been modified, and obviously, the animals suffer,” he said. “We want the zoo to be a conservation tool, not a park for walking dogs, because we have that already.”

Text from the AP news story, Animals still in cages a year after Buenos Aires zoo closure, by Luis Andres Henao.

Photos by Natacha Pisarenko

Natacha Pisarenko on Instagram

Follow AP photographers on Twitter

Written content on this site is not created by the editorial department of AP, unless otherwise noted.

Visual artist and Journalist