50 years since Bobby Fischer won international chess crown

On Sept. 1, 1972, American Bobby Fischer won the international chess crown in Reykjavik, Iceland, as Boris Spassky of the Soviet Union resigned before the resumption of Game 21.

The 29-year-old chess genius from Brooklyn, N.Y. brought the U.S. its first world chess title in the competition that took place from July 11 - Sept. 1, 1972. The match had the first of several controversies before it began, when it was delayed by Fischer, who demanded more money and would not travel until the winning pot was increased, and then by Spassky, who would not begin play until Fischer apologized.

Game 21 began on Aug. 31, and after being adjourned overnight, ended with Fischer amassing 12 1/2 points to the 35-year-old Spassky’s 8 1/2 points.

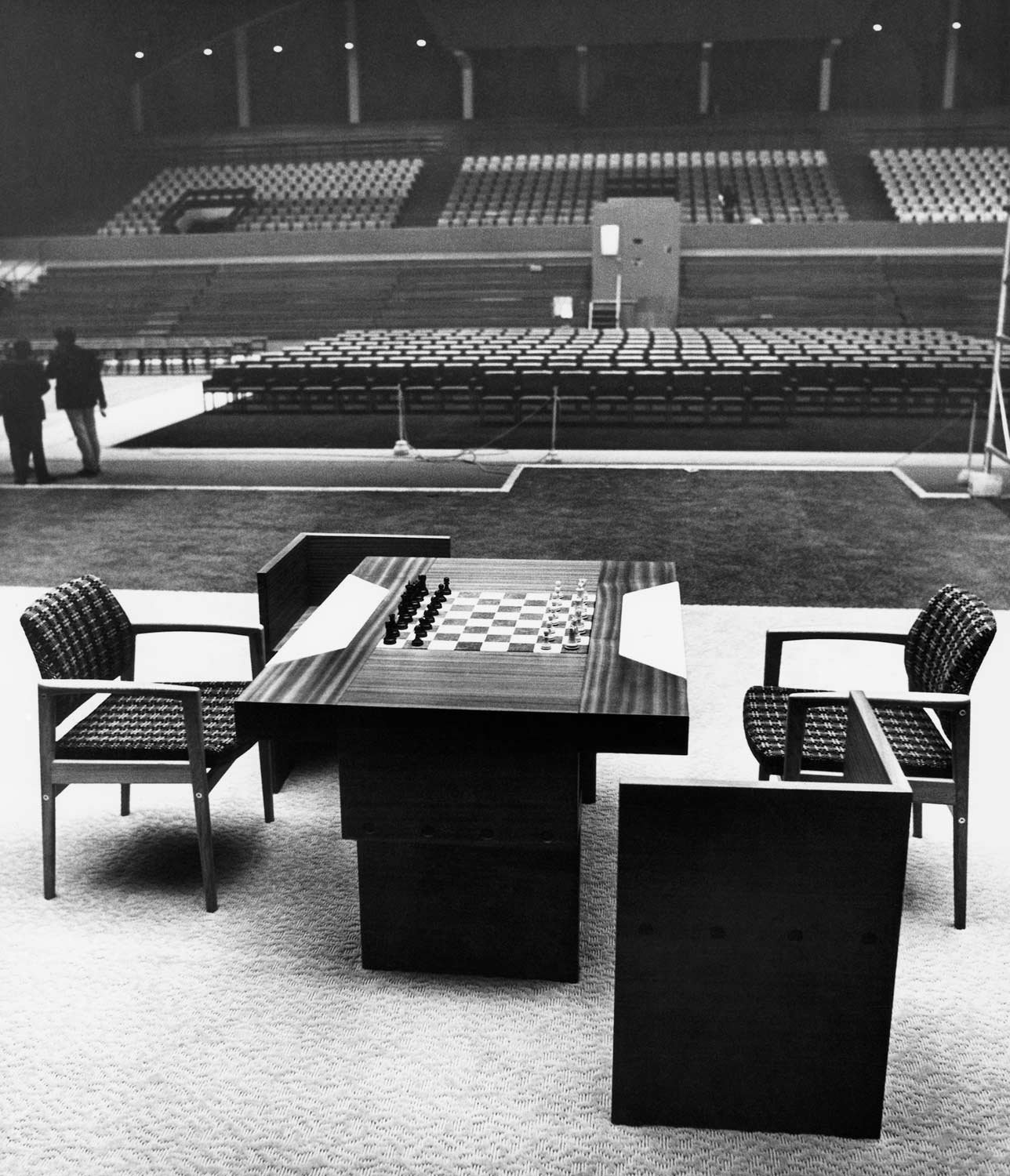

The chess table and chairs, which are to be used by Bobby Fischer and Boris Spassky for the international chess crown, sit empty in the vast Laugardalsholl Hall on Tuesday, July 4, 1972 in Reykjavik, Iceland. (AP Photo/Johann)

The following text is an excerpt from The Associated Press article, "Fischer—From Prodigy to Superstar," by Louise Cook, on Friday, Sept. 1, 1972.

When Bobby Fischer won his first U.S. chess championship at 14, the world called him a prodigy. Now that at 29 he has defeated Boris Spassky for the world title, people are calling him a superstar.

For Fischer, however, the victory over the Russian is simply what he felt he deserved. "I’m tired of being the unofficial champion," he said several months before the match in Iceland got under way.

"It’s nice to be modest, but it would be stupid if I did not tell the truth. I should have been world champion 10 years ago."

Ten years ago, Fischer finished a surprisingly poor fourth behind three Russians in the tournament playoffs. He promptly accused the Russians of cheating, insisting that they used the round-robin format to their advantage by playing easy matches to draws against each other and saving the tough stuff for him.

In 1965, the International Chess Federation scrapped the round-robin in favor of the player-to-player eliminations that led Fischer to the Reykjavik match.

The American challenger began with a victory at the internal finals in Palma de Mallorca and went on to amass an unprecedented 20 straight wins.

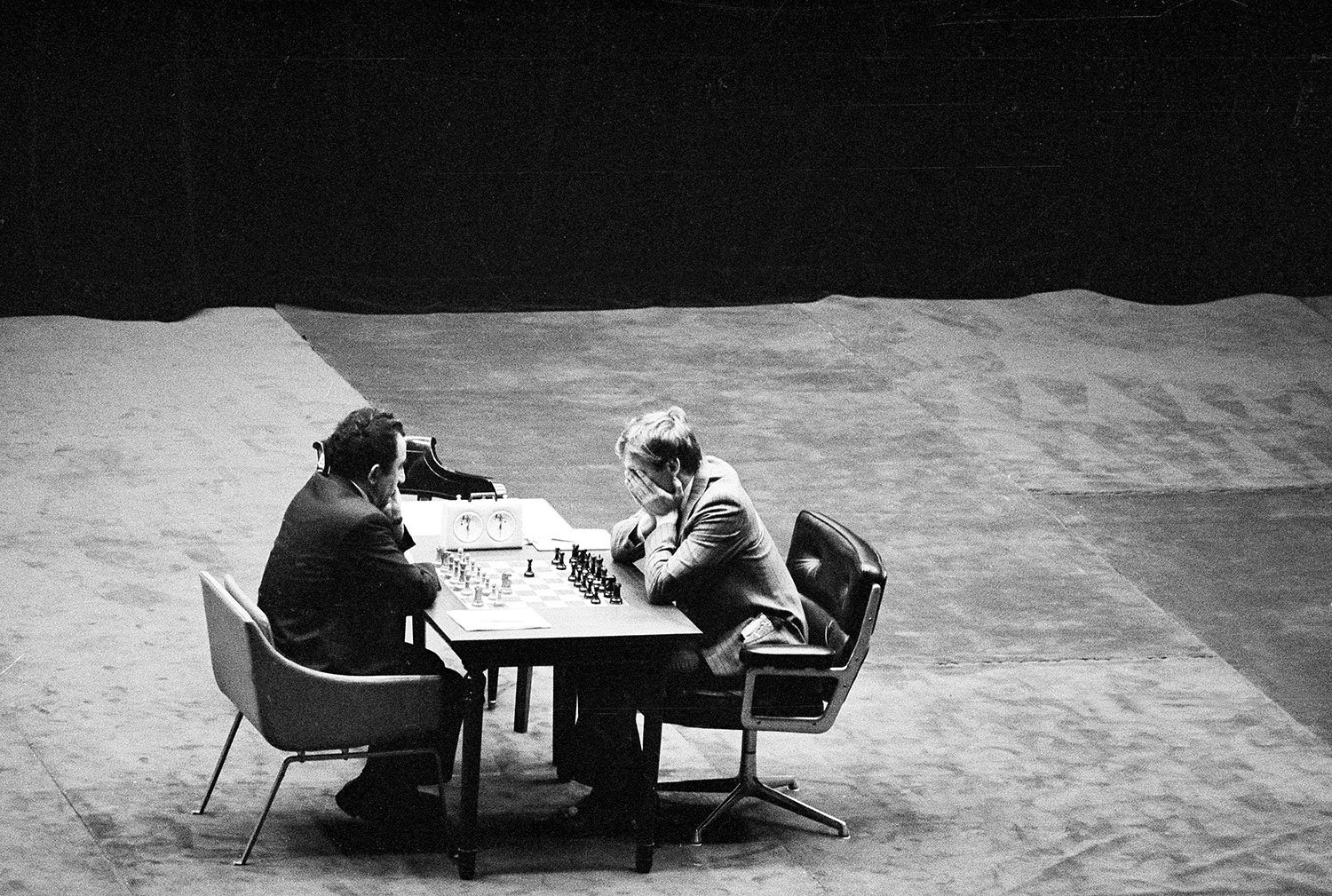

Bobby Fischer of the U.S., right, and Tigran Petrosian of the U.S.S.R., continue the sixth game of their semi-final series for the world chess title, Sunday, Oct. 17, 1971, in Buenos Aires. Fischer won that game. (AP Photo/Domingo Zenteno)

The Soviet Union’s Tigran Petrosian broke Fischer’s winning streak in the second game of their semifinal match in Argentina last November, but the U.S. player ultimately defeated the Russian 6 1/2 to 2 1/2 winning $7,500 in prize money and the right to meet Spassky.

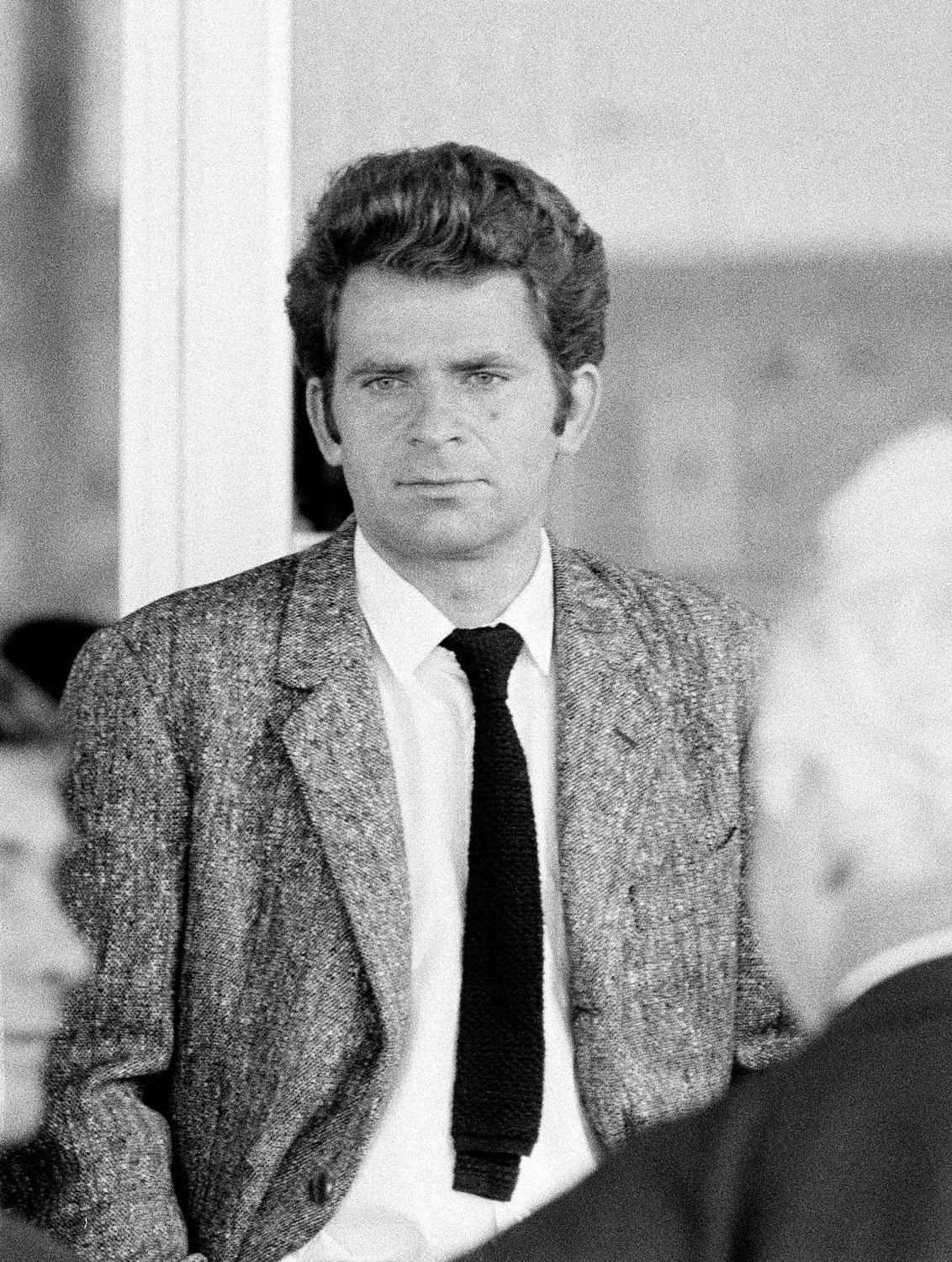

Chess player Boris Spassky talks to Soviet officials outside his hotel in Reykjavik, Iceland, Sunday, July 2, 1972. Spassky is in Iceland to compete against American Bobby Fischer in the world championship, but Fischer, claiming illness, did not appear for the match originally scheduled for Sunday. (AP Photo)

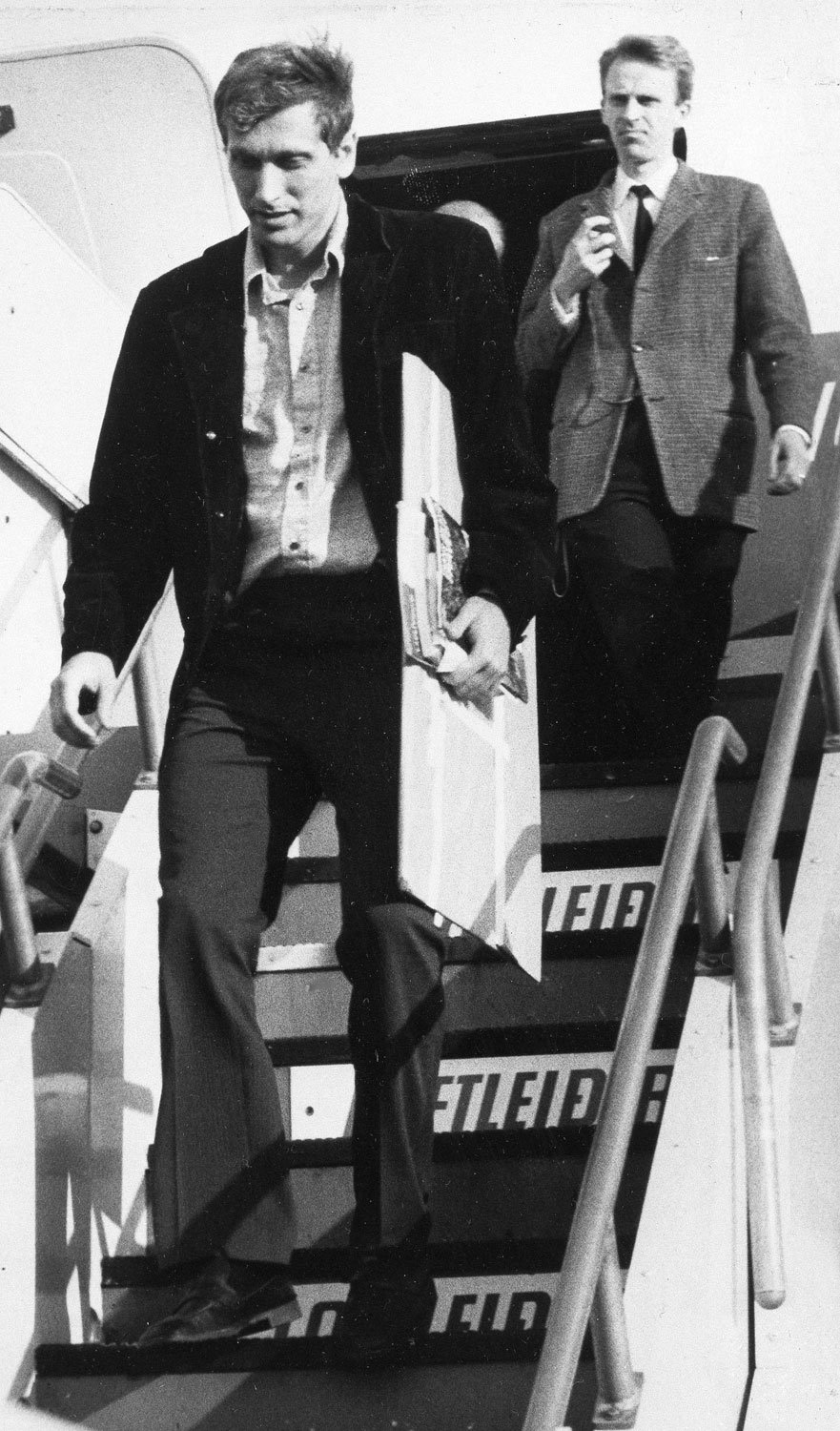

American grandmaster chess player Bobby Fischer steps off a plane in Reykjavik, Iceland, Tuesday, July 4, 1972, where he is to meet world champion Boris Spassky in the world championship series later in the day. Fridrik Olafsson, Icelandic chess grandmaster, stands behind Fischer on the right. (AP Photo)

Bobby Fischer arrives at Keflavik Airport in Reykjavik, Iceland, to compete in the world chess championship, Tuesday, July 4, 1972. (AP Photo)

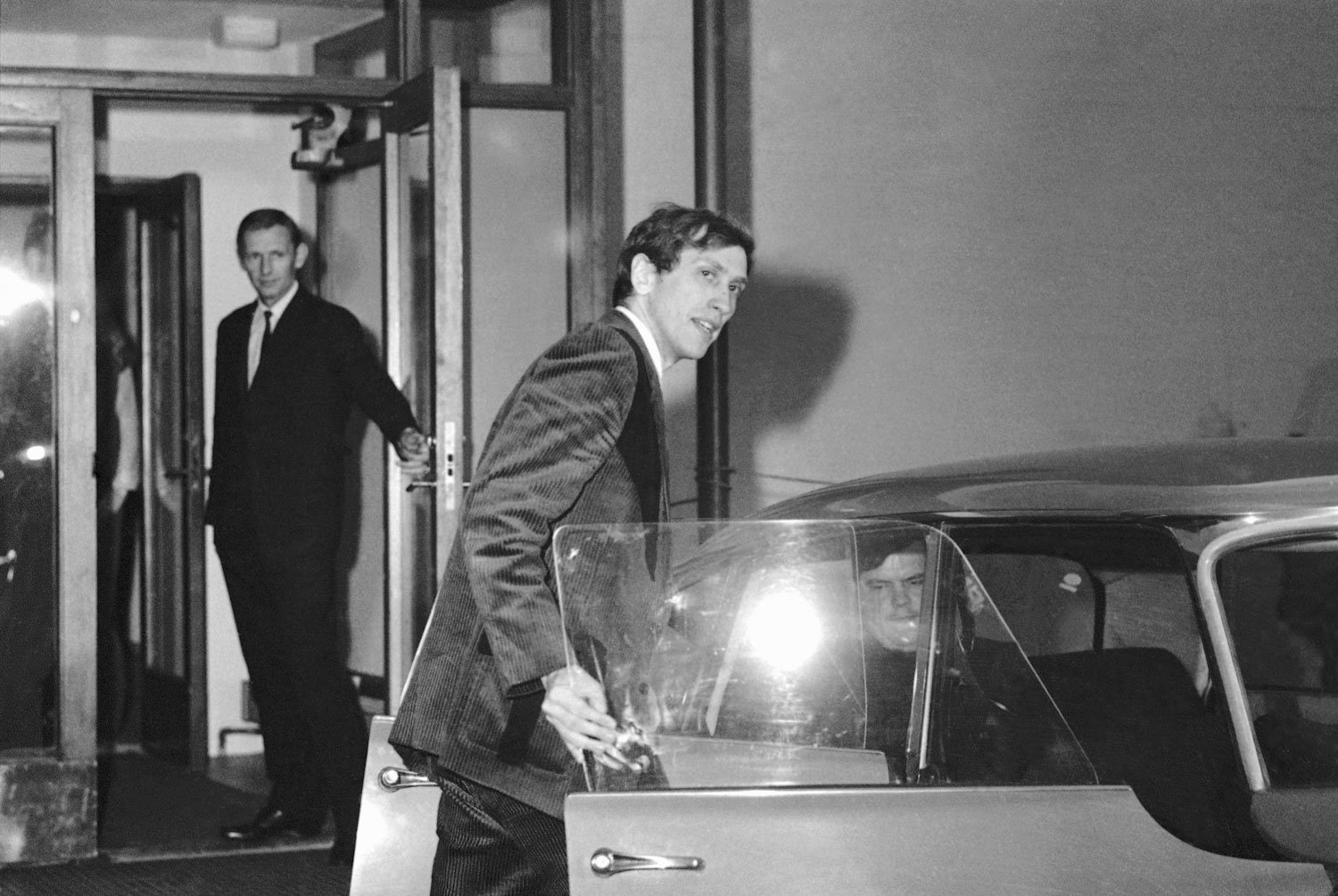

Icelandic police keep the crowds back to make way for Bobby Fischer's auto as he departs Keflavik Airport in Reykjavik, Iceland, Tuesday, July 4, 1972. Fischer arrived in Iceland to meet Soviet titleholder Boris Spassky in the world chess championship series slated to begin later in the day. (AP Photo)

World chess champion Boris Spassky, of the Soviet Union, signs autographs for children in Reykjavik, Iceland, Thursday, July 6, 1972 after a tennis match with his compatriot Jivo Nei. Spassky is scheduled to defend his title against American grandmaster Bobby Fischer. (AP Photo)

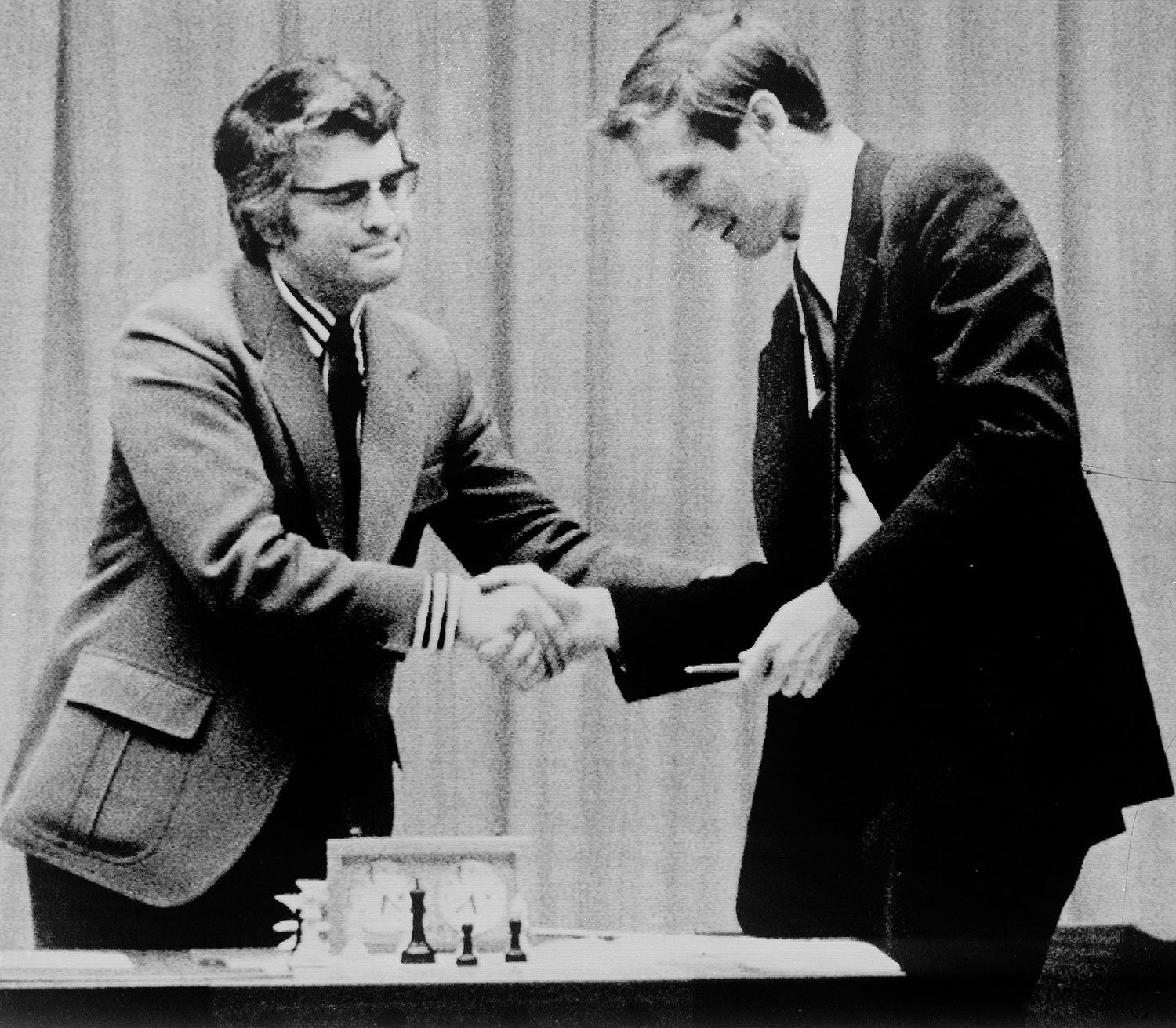

Boris Spassky shakes hands with Bobby Fischer after Spassky won the game at Laugardalsholl Hall in Reykjavik, Iceland, Wednesday, July 12, 1972. (AP Photo)

Boris Spassky, chess master of the U.S.S.R., leaves the Reykjavik Chess Hall after Bobby Fischer failed to appear for the second game of the world chess championship, Thursday, July 13, 1972. Fischer's absence from the game gave Spassky a 2-0 lead in the scheduled 24-game series. Fischer objected to film crews in the playing hall which he said he found distracting. (AP Photo)

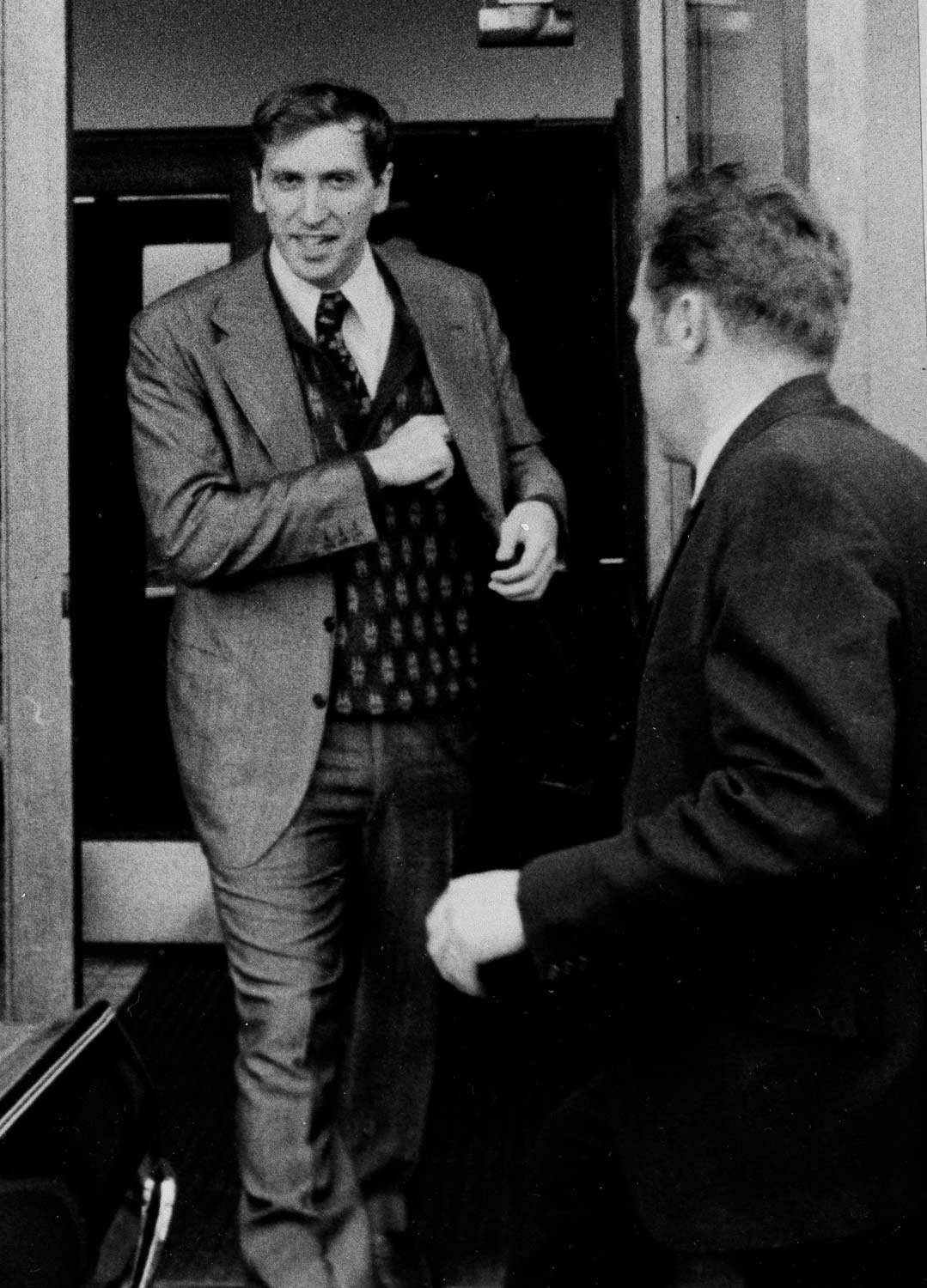

Bobby Fischer is seen leaving the Laugardalsholl Hall with a smile after winning the chess game against world champion Boris Spassky, Monday, July 17, 1972. (AP Photo)

Boris Spassky, carrying a bag with a thermos of hot coffee, enters Laugardal Stadium on Thursday, Aug. 24, 1972 in Reykjavik, Iceland, for his 18th game of world chess championships with Bobby Fischer. (AP Photo/J. Walter Green)

American chess grandmaster Bobby Fischer walks toward Laugardal Stadium in Reykjavik, Iceland, Wednesday, Aug. 23, 1972, for the 17th game in the World Chess Championships. (AP Photo/J. Walter Green)

American chess champion Bobby Fischer walks out of Laugardalsholl Hall in Reykjavik at night on Monday, Aug. 28, 1972, with a smile as he had another draw with Boris Spassky, of the USSR, in their world chess championship match. (AP Photo/J. Walter Green)

The following text is an excerpt from The Associated Press article, "Fischer Wins Chess title as Spassky Resigns 21st Game," by Julie Flint, on Saturday, Sept. 2, 1972.

Bobby Fischer won the world chess championship Friday without moving a pawn. He became America's first world titleholder when Boris Spassky resigned by telephone in the 21st game, his position analyzed as hopeless.

The 29-year-old chess wizard from Brooklyn stands to win $156,000 in prize money and can count on more thousands from book royalties, public appearances and the like.

Bobby Fischer, of the United States, right, and Boris Spassky, of the U.S.S.R., play their last game together in Reykjavik, Iceland, Thursday, Aug. 31, 1972. The game was adjourned overnight. (AP Photo/J. Walter Green)

Fisher’s victory in the 21st game, adjourned overnight, gave him 12 1/2 points to the Russians 8 1/2.

Spassky, 35, will receive about $100,000. He won only three games, one on a forfeit, and Fisher seven. They drew 1 time, each draw counting half a point.

When referee Lothar Schmid stepped forward on the stage and announced that Spassky had resigned, the spectators in the jammed hall cheered. Schmid shouted “Brave Bobby“ as Fischer smiled. Fisher then left quickly and fans mobbed his car outside the hall.

Col. E.B. Edmondson, head of the American Chess Federation (stated) the victory was “entirely what we expected” and “the score was exactly what I predicted months ago.”

Tass, the Soviet news agency, said Spassky's "decision was taken after an analysis showed that further white resistance was futile." Spassky has played the opening white pieces, ordinarily an advantage.

There was a last minute fuss when the championship changed hands. Schmid had received the telephone call from Spassky at 12:50 p.m. The resumed game was to have begun at 3:30 p.m.

Schmid said he had congratulated Spassky on his sportsmanship and asked him to go to the playing hall to inform Fischer officially. Spassky did not go and the Americans, told of the telephone call, refused to accept the resignation as official.

Max Euwe, president of the International Chess Federation, ruled that Fischer would have to show up on stage to be declared the champion. When Fischer arrived, he still was not sure Spassky had resigned.

Lothar Schmid of West Germany, left, chief referee of the World Chess Championship, shakes the hand of American chess star Bobby Fischer, telling him he is the winner of the match after Boris Spassky resigned by telephone, Friday, Sept. 1, 1972, in Reykjavik, Iceland. (AP Photo/J. Walter Green)

The referee said Fischer insisted on seeing if the Russian had signed his score sheet to make the resignation valid. Schmid had signed the score sheet and explained to Fischer that this was valid under federation rules.

Schmid then announced the Soviet champion’s resignation to the 2,500 Icelanders assembled in the hall.

Bobby Fischer of the U.S. leaves Laugardalsholl Hall in Reykjavik, Iceland, after winning the world chess championships against Boris Spassky of the U.S.S.R., Friday, Sept. 1, 1972. (AP Photo/J. Walter Green)

Thus the match that had excited the imagination of the world ended in anti-climax, instead of in the killing attack by Fischer that the fans had expected.

Russians had dominated the chess world for 35 years, and the dream of Fischer’s life had been to end the domination.

The match had been dominated by controversy, first over Fischer’s demands for more money and later by his complaints about plane conditions. So relations between the American and the Russian were strained.

Euwe said he wished Spassky had shown up to congratulate Fischer but noted that the Russian "was a little bitter."

New world chess champion Bobby Fischer, of the United States, is greeted by young chess fans in Reykjavik, Iceland as he returns to his hotel room after he won the championship following Boris Spassky's resignation in the 21st game, Friday, Sept. 1, 1972. (AP Photo)

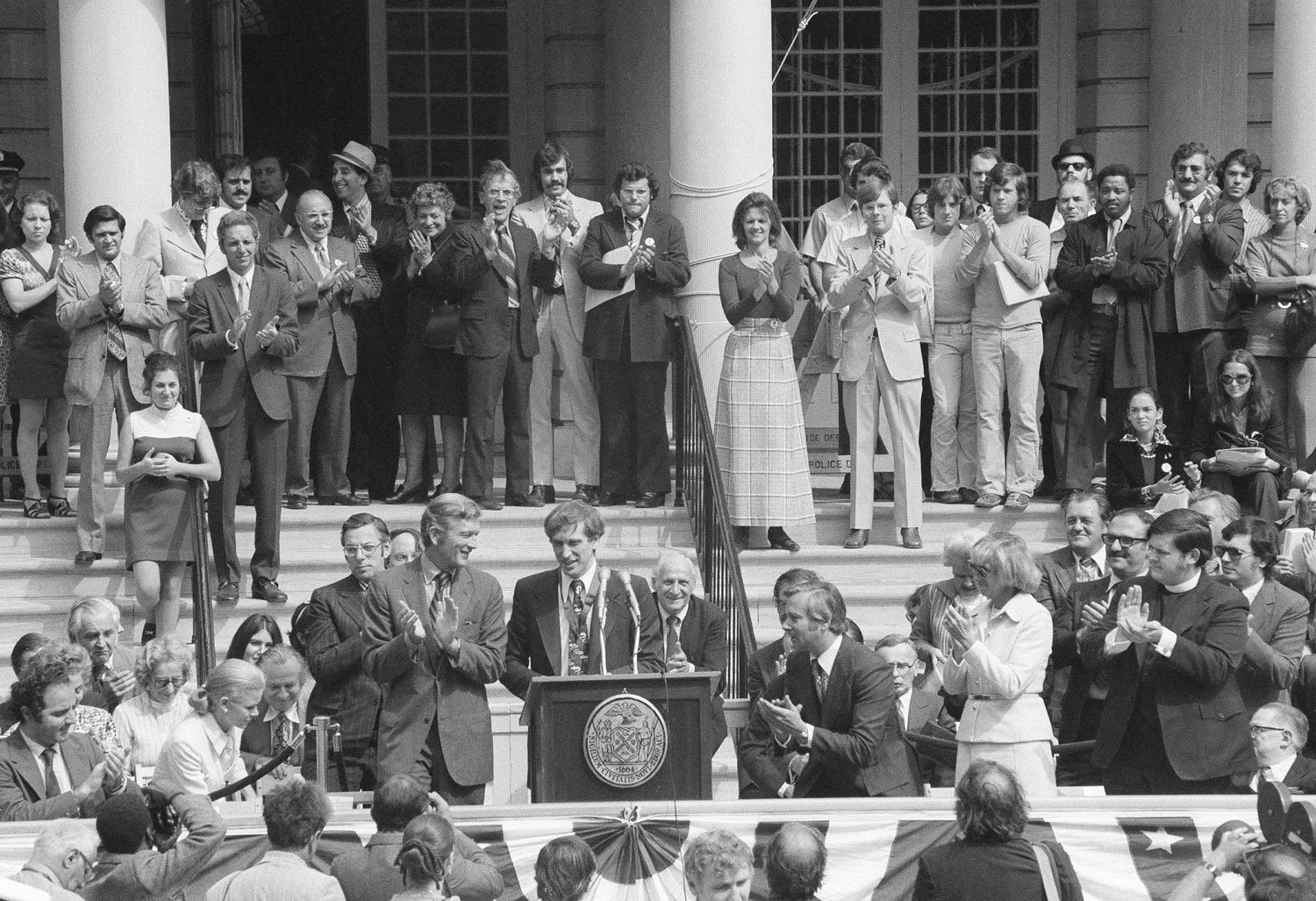

World chess champion Bobby Fischer speaks at the podium during the proclamation of "Bobby Fischer Day" by New York Mayor John V. Lindsay, left of Fischer, at New York's City Hall, Friday, Sept. 22, 1972. (AP Photo)

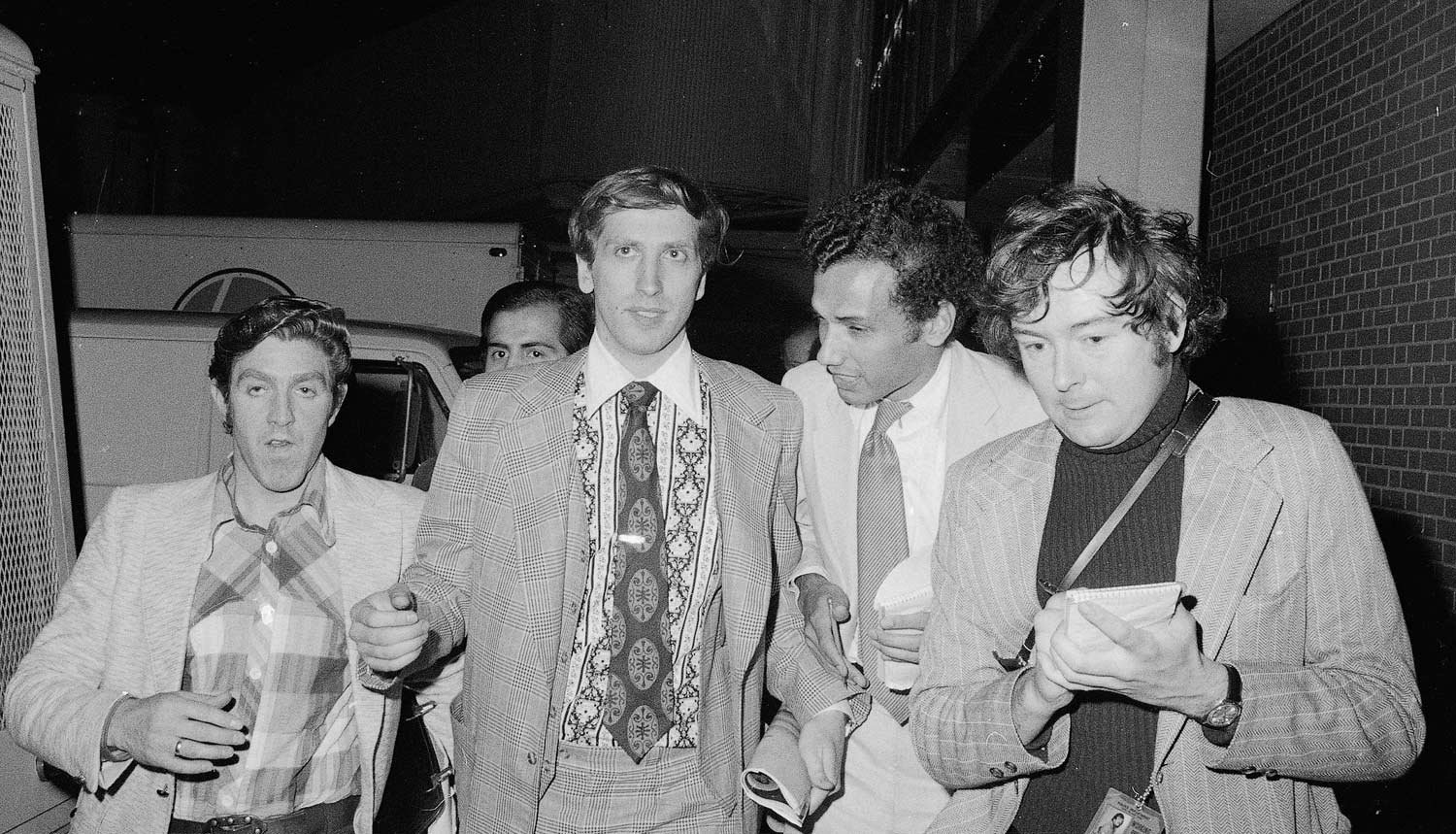

World chess champion Bobby Fischer, center, is flanked by reporters on his arrival at New York's Kennedy Airport, Sunday, Sept. 17, 1972. Fischer took the world title away from Boris Spassky, of the U.S.S.R., in a tournament in Reykjavik, Iceland earlier this month. (AP Photo)

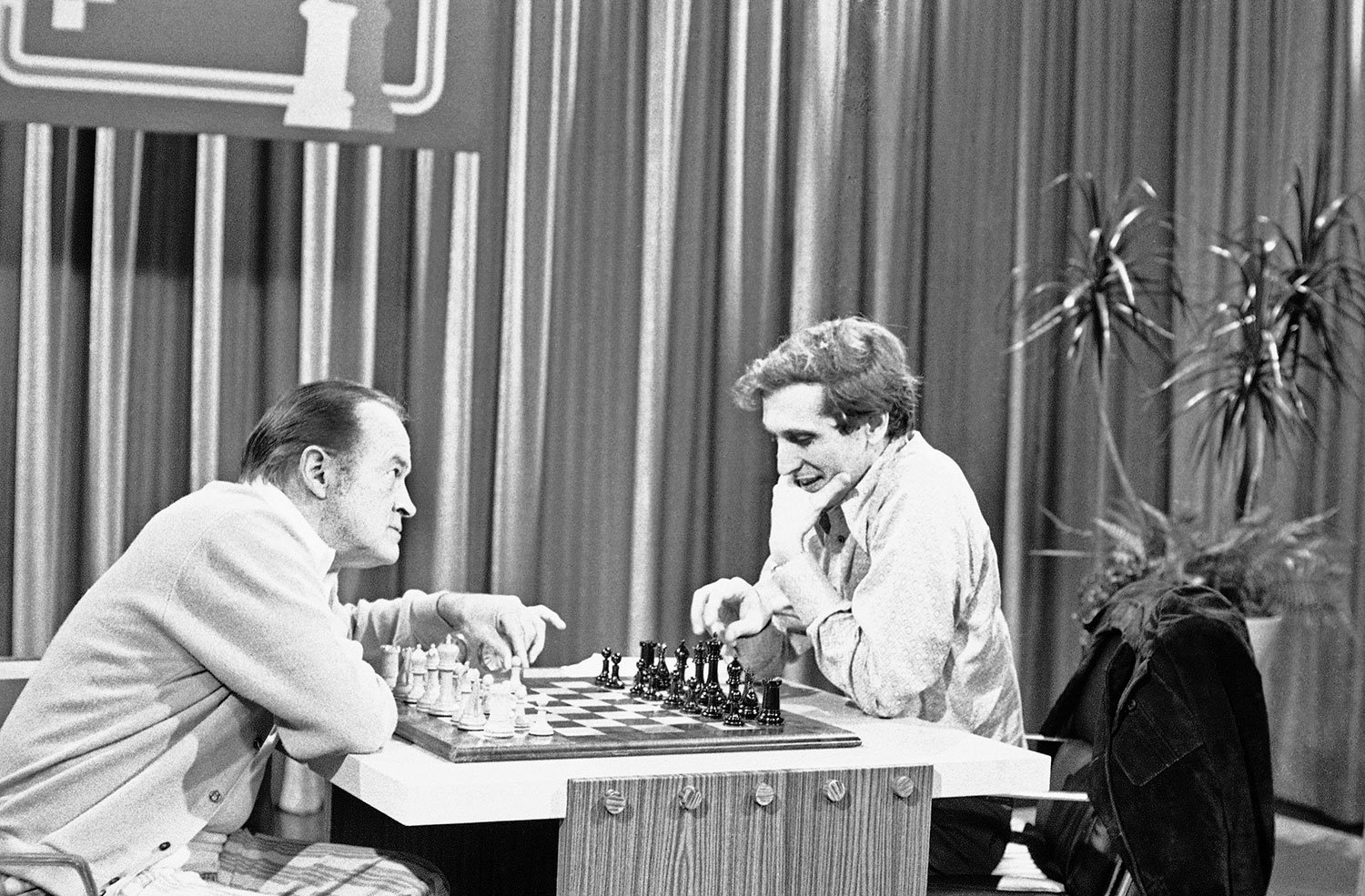

Bob Hope holds on to his chess piece as he watches to see what Bobby Fischer, the world champion chess player, will do as they rehearse on Oct. 1, 1972 in Burbank, Calif., for Fischer's guest appearance on the Bob Hope TV special on October 5. Fischer recently beat Boris Spassky, the Russian champion, for the world title in Iceland. (AP Photo/DFS)

Text Excerpts

From "Fischer—From Prodigy to Superstar," by Louise Cook, published in the Oakland Tribune on Friday, Sept. 1, 1972.

From "Fischer Wins Chess Title as Spassky Resigns 21st Game," by Julie Flint, published in The Times, Saturday, Sept. 2, 1972.

Text and photo editing by Kathleen Elliott

AP Photo archive on Instagram

See these photos on AP Images