The 1932 Bonus Army and the Great Depression

The Wall Street stock market crash of October 1929 marked the start of the disastrous years of The Great Depression. By 1932, 25 percent of the country’s workforce was unemployed. Tens of thousands of World War I veterans were among those affected by the collapse of the economy. Many of them joined the “Bonus Army.”

Under the Adjusted Compensation Act of 1924, veterans of World War I were granted a monetary “bonus” for service in the United States armed forces. The vets received a “bonus certificate,” a piece of paper, that couldn’t be cashed until 1945. Payments would range from about $500 to $700.

In the spring of 1932, Rep. Wright Patman of Texas proposed a bill to make the payments available immediately. With the house set to vote on Patman’s bill in June of that year, impoverished and desperate veterans organized to support the bill by heading to Washington. The first major contingent of protesters, under the leadership of Walter W. Waters of Portland, Oregon, who became the commander in chief of the bonus marchers, arrived in Washington on Memorial Day, 1932. In the coming weeks, some 40,000 demonstrators, including 17,000 veterans of World War I, assembled in the capital to support immediate payment of the promised bonus. The protesters, dubbed the “Bonus Army” or the “Bonus Expeditionary Force,” set up encampments near the Capitol and along the banks of the Anacostia River.

Members of the Workers' Ex-Service Men's League, described as a radical element of organized veterans, march to City Hall in New York to demand the city lend them motor trucks to transport them to Washington to participate in the demonstration there, June 3, 1932. (AP Photo)

Three men stand in front of the dispensing kitchen of the Greater New York Philanthropic Society where penny meals, that are quite substantial, are served to the hungry, in New York, Aug. 3, 1932. The soup kitchen has been functioning since 1908 and is supported by private contributions. (AP Photo)

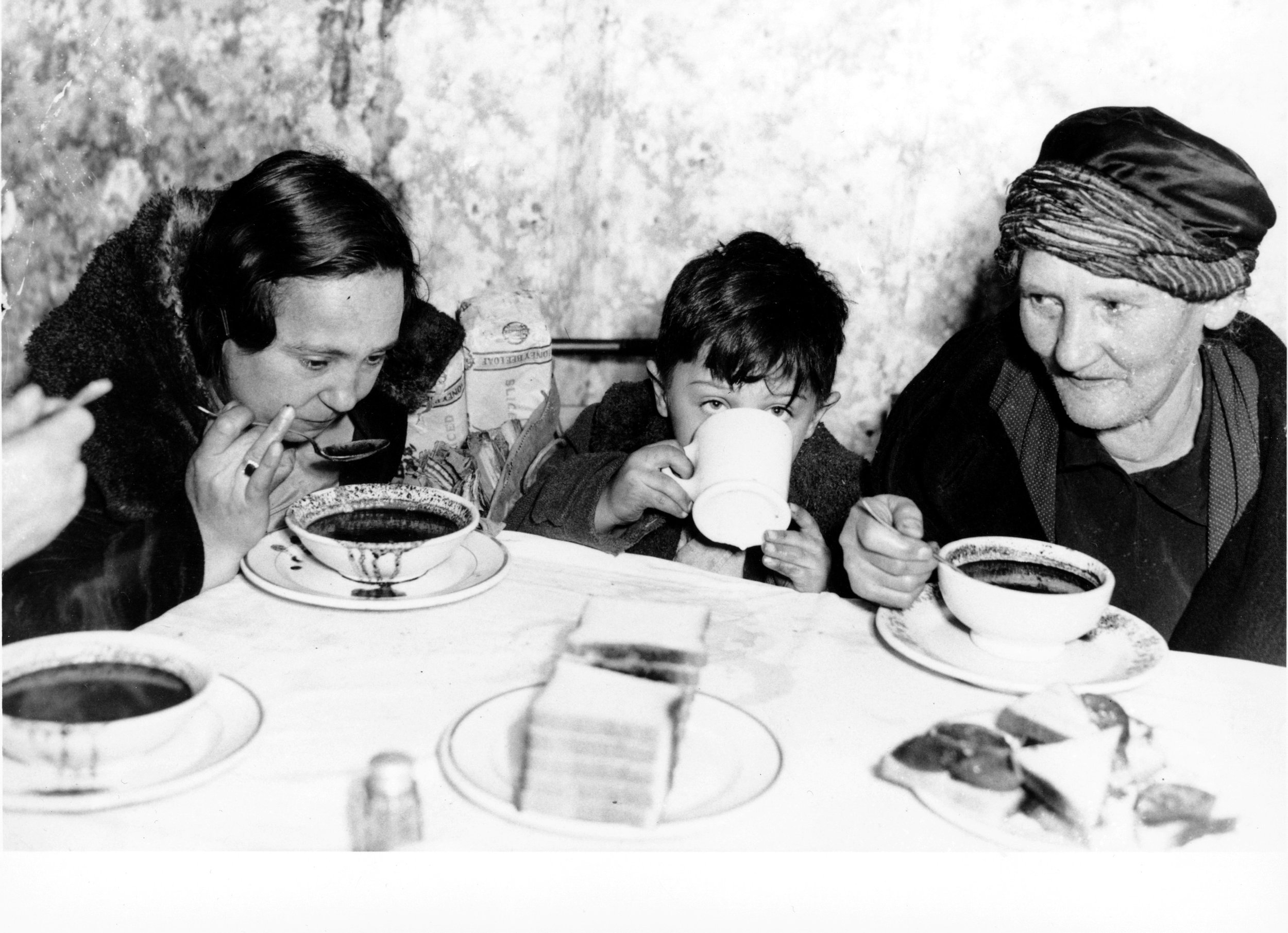

Hundreds of hungry men standing shivering as they wait for their turn for a sandwich and a cup of coffee, in the Times Square district of New York City, 1932. The sight is in stark contrast to the dazzling bright lights of Broadway. (AP Photo)

Eleanor Roosevelt ladles soup into a bowl in the Grand Central Restaurant kitchen in New York City on Dec. 1, 1932 during the Great Depression. The U.S. president-elect's wife walked into the restaurant's kitchen to help feed unemployed women. (AP Photo)

This group of unemployed veterans of the World War left Columbus, Ga. and Girard, Ala. on a long trek to Washington to demand payment of the soldier's bonus, June 2, 1932, near Lawrenceville, Ga.. The men carried their own provisions and traveled in two trucks. (AP Photo)

Frank Tracy of Pittsburgh, Pa., and his six children are photographed in front of their tent shelter in one of the Bonus Expeditionary Force's encampments around Washington D.C., June 19, 1932. Left to right is Virginia, 12, Frank, 9, Margaret, 7, Ethel, 4 1/2. In Tracy's arms are Howard, 3, Ruth, 1. They are shown saluting their father as an observance of Father's Day. (AP Photo)

A group of former war veterans who remain firm in their demands for the payment of the bonus, shown as they arrived at the capitol in WASHINGTON, on July 5, 1932. They heard their speakers demand again relief for the former soldiers , and then quietly dispersed. (AP Photo)

Major General Smedley Butler addresses nearly 16,000 veteran bonus marchers camped in Washington, D.C., July 20, 1932. Smedley urged them to stay until the bonus has been paid. (AP Photo)

For more than two months in the summer of 1932, World War I veterans from all over the country converged on Washington, D.C., to demand passage of a bill which would provide early payment of bonuses. Here, vets standing in silence as body of one of their champions, Rep. Edward Eslick of Tennessee, is borne past. Eslick died of a heart attack on June 14, 1932 while delivering a speech in favor of the bill in the House of Representatives. (AP Photo)

Denizens of the Destitute Artists' Camp prepare food at their encampment during the Bonus Army march in Washington, D.C., 1932. (AP Photo)

Crowded into 5 trucks and 12 automobiles, about 125 hunger marchers and 25 Bonus Army Veterans prepare to leave St. Louis for Washington, D.C., Nov. 29, 1932, to demonstrate for unemployment relief and prompt payment of the bonus. Here is a group of the marchers before the start. (AP Photo)

Veterans of Bonus March gather around a piano to sing at their encampment in Washington, D.C., in June 1932. (AP Photo)

Veterans of the Bonus March line up at the ticket office at Union Station in Washington, D.C., to take advantage of the $100,000 appropriation made by Congress to provide rail transportation back to their homes, July 11, 1932. They came with the Bonus Army Expeditionary Force to the nation's capital to seek bonuses for their services in World War I. (AP Photo)

Patman’s bill passed the House, but on June 17, 1932, it was soundly defeated in the Senate by a vote of 62 to 18. Although Waters vowed to continue the fight, many veterans and their supporters began to trickle out of the city. Some chose to stay and continue the protest. On July 28th, the police attempted to evict about 50 marchers who were camped along Pennsylvania Avenue; they shot and killed two of the protesters. President Hoover ordered the Army to continue the evictions. With bayonets, tear gas and tanks, the Army under the command of Douglas MacArthur, with his aide Major Dwight D. Eisenhower and tank commander, Major George S. Patton drove the remaining protesters from the Capitol area, and continued across the river to rout the 10,000 protesters who were still encamped on the Anacostia Flats.

Praise for Hoover’s response was not universal. Many Americans were shocked and dismayed to see American troops turn their weapons on fellow citizens. The Washington Daily News editorialized: “If the Army must be called out to make war on unarmed citizens, this is no longer America."

Sporadic demonstrations by veterans and supporters continued in the coming years. It wasn’t until 1936 that Congress eventually released close to $2 billion dollars for veterans benefits.

Chief of Staff Douglas MacArthur, standing against bridge wall with a cup of coffee, rests with troops during a break in the Army's drive to evacuate war veterans camped out in Washington, D.C., in 1932. World War I veterans from across the country have gathered in Washington on a two-month long march on the Capitol demanding passage of a bill that would provide early payment on bonuses. MacArthur's troops eventually cleared the veterans and burned their shacks. (AP Photo)

Troops Rout The Veterans

Washington, July 29, 1932 (AP)

(Excerpt)

The four wretched encampments, which for two months past have housed the bonus army, lay burned to earth early this morning, and the veterans who have lived there sought haven in dark streets, on country roads and the path homeward.

One of their number had been shot dead by police. More than 50 veterans, policemen, soldiers and spectators were injured in the battles.

That affray near the Capitol in the afternoon, led to President’ Hoover’s calling upon federal troops to clear the camps, which they did with the use of tear gas.

In late afternoon and early evening, they successfully attacked the three shanty sites in the city proper, applying the torch once the veterans had fallen back.

Last night, it had been decided to hold off drastic actions in the main Anacostia camp until today at least. One after another, blaze broke out in huts where the veterans were, and that portion of the city was cast in a glare that could be seen by the president as he retired at the White House.

Finally it was determined to let the troops complete the destruction. They did, and set up a guard there such as was watching over the other three scenes of the attack.

In Washington, D.C., a cavalry led by Major George S. Patton routed an "army" of his fellow World War I veterans, their wives and children, who protested to beseech Congress for promised bonuses, 1932. (AP Photo)

U.S. veterans are shown during the Bonus March on Washington, July 28, 1932. (AP Photo)

Almost in the shadow of the towering Washington Monument, bonus veterans' camp is burned down in Washington, D.C., July 28, 1932, after the veterans has evacuated before the threats of government troops. Some of the men fired their own huts, although the troops set fire to many. (AP Photo)

A federal soldier passes by burning shacks that fleeing Bonus March veterans abandoned, at Camp Marks, on the Anacostia Flats in Washington, D.C., July 29, 1932. This was the fourth veterans' camp to be burned. (AP Photo)

A war veteran and his wife huddle in the street the morning after the eviction of bonus-demanding veterans and the burning of their camp by government troops in Washington, D.C., July 28, 1932. He is sleeping on the sidewalk while his wife sits by wrapped in the blankets that comprised their sole belongings. (AP Photo)

A committee of writers appears at the White House to protest against the use of U.S. military troops in the eviction of the Bonus Army Marchers from Washington, on August 10, 1932. The men are, from left: novelist Sherwood Anderson, Elliott E. Cohen, from Mobile, Ala., secretary of the National Committee for the Defense of Political Prisoners, Waldo Frank, New York novelist, William Jones, editor of the Baltimore Afro-American, and James Rorty, poet and critic, from Westport, Connecticut. (AP Photo)

With his name attached to homeless encampments (Hoovervilles), and his unwillingness to provide direct relief to the destitute, Hoover’s popularity was at a low ebb for the 1932 presidential election. In November 1932 he was defeated in a landslide by Democrat Franklin Delano Roosevelt. It was now up to Roosevelt to deliver on his promise of a “new deal for the American people.”

President Herbert Hoover and first lady Lou Henry Hoover stand on the rear platform of their special train as it leaves Washington, D.C., Oct. 3, 1932. President Hoover is en route to Des Moines, Iowa, where he'll deliver his first campaign address since accepting the Republican Party renomination. (AP Photo)

John Nance Garner, Democratic Vice-Presidential nominee, and New York Gov. Franklin D. Roosevelt, Democratic Presidential nominee, pose on the rear of Gov. Roosevelt's private train at Topeka, Kansas, where the governor made a campaign speech, Sept. 14, 1932. (AP Photo)

Text and photo editing by Francesca Pitaro.

AP news story July 29, 1932, excerpted from “20th Century America.”

See these photos on AP Images