AP at 175, Part 7: Speed, 1976-2000

The Associated Press (AP) celebrates its 175th birthday in 2021. To mark this milestone, the AP Corporate Archives has assembled a concise visual history of the organization, offered here in an eight-part monthly blog, “AP at 175.” This is the seventh of eight installments.

Valerie S. Komor

Director, AP Corporate Archives

The AP began the last quarter of the 20th century with one foot firmly in the computer age. Under General Manager Keith Fuller, who served from 1975 to 1984, AP made the transition from leased wires to satellite transmission of news. By 1986, with DataStream on the horizon and the capacity to deliver 9,600 words of copy per minute, the last teletype was taken out of service at the West Plains (MO) Daily Quill.

In January 1985, Louis D. Boccardi, who had joined AP in 1967 as assistant to the general news editor, became the AP’s president and general manager. Renowned as an editor, Boccardi proved equally adept at steering the business side of AP operations in an extremely competitive environment. The only constant was the need for change. Innovation in news and photo delivery were part of AP’s playbook and AP met those challenges time and again, most notably with the introduction of Photostream and the electronic darkroom, the development of the NC2000 digital camera and the creation of AP’s digital photo archive. Under Boccardi, AP also expanded its reach in the media arena, entering the video market in 1994 with the launch of APTV in London. In 1998 AP purchased WTN (Worldwide Television News), which combined with APTV to create APTN, a global video news service. AP’s own internet service, The Wire, launched in 1996, providing text, photos, audio, and video news, updated with the latest reporting.

Boccardi never lost sight of AP’s mission, nor took for granted the sacrifices made by staff in the field. On March 16, 1985, Chief Middle East Correspondent Terry Anderson was kidnapped by Hezbollah militants near his apartment in Beirut. Working behind the scenes with a team led by AP’s Larry Heinzerling, Boccardi was relentless in his efforts to free Anderson, who was finally released on December 4th, 1991 after 6 ½ years in captivity.

Terry Anderson with Associated Press President and CEO Lou Boccardi in December 1991. (AP Photo)

“I just kept the shutter down.”

Ron Edmonds

AP photographer Ron Edmonds was a new hire assigned to the White House, reporting for his second day of work on March 30, 1981. As part of the traveling pool covering President Ronald Reagan, Edmonds was waiting outside as the President left the Washington Hilton Hotel after giving a speech. Almost immediately, John W. Hinckley Jr. fired six shots, wounding the President, White House Press Secretary James Brady, Secret Service agent Tim McCarthy, and police officer Thomas Delahanty.

Edmonds, using his motor-driven camera, recorded a perfectly focused series of photos of the events as they unfolded. His photos of the assassination attempt won the 1982 Pulitzer Prize for spot photography. On January 20, 1989 Edmonds snapped the first digital news picture at the inauguration of George H. W. Bush as president. Edmonds retired in 2009.

Edmonds described how he got the Reagan photos in the April 6, 1981 issue of The AP Log:

”I positioned myself on the driver’s side of the limousine to get some pictures across the top of his car as Reagan came out the door. As he approached the limousine waving first to his right and then to this left, I clicked my first frame. I heard a “pop” and saw him react. I kept the shutter down on my motorized camera and continued shooting frames as Secret Service agents pushed the president into the car. I thought someone had thrown a string of firecrackers.

As the limousine moved out, I swung to my right and started making pictures of the gunman being wrestled to the ground. It was then that I spotted the three wounded men on the ground. That’s when I first realized that what I had heard was gunfire. Everything happened so fast, I didn’t have time to think about anything except technical aspects of my camera. Ira Schwarz, another AP photographer who had been inside the Hilton, came out and I handed him my film. He jumped into a cab and raced the film to the bureau.

I continued making pictures as the three wounded men were placed in ambulances. The emotional impact finally struck me as I heard someone say press secretary James Brady, whom I had often had coffee with, was one of those wounded.”

In this Monday, March 30, 1981 combination file photos, President Reagan waves, then looks up before being shoved into Presidential limousine by Secret Service agents after being shot outside a Washington hotel. (AP Photo/Ron Edmonds)

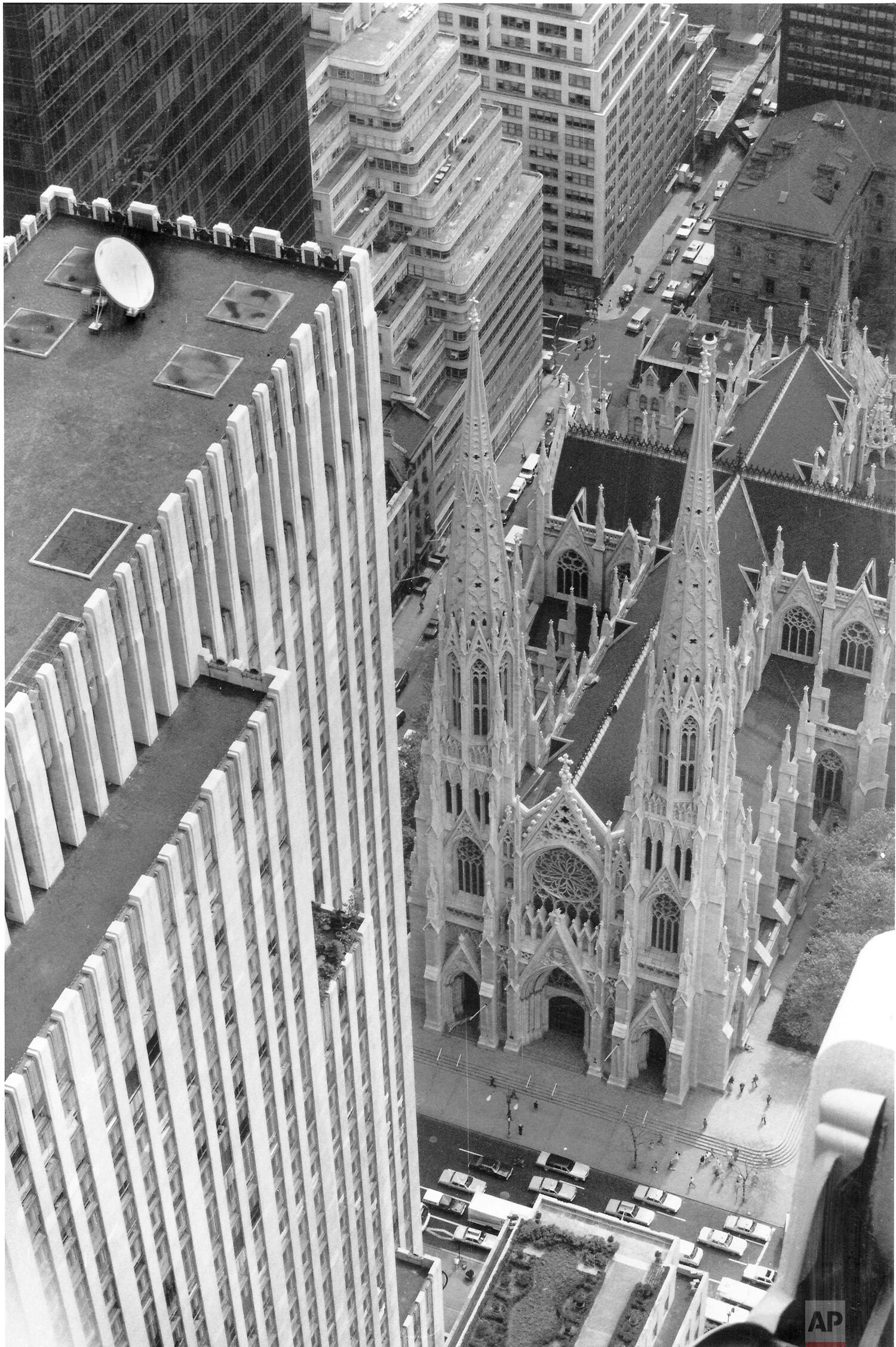

View of an AP satellite antenna on top of the International Building on New York's Fifth Avenue in 1985. (AP Photo/Corporate Archives)

Cover of an AP SATNET brochure, 1990s. (AP Photo/Corporate Archives )

“In photography, everything has changed. What has not changed is the need for really fine photography, story telling pictures.”

Hal Buell

Hal Buell started his AP career in 1954 as a part-time staffer in the Tokyo bureau while serving with the Army on the Pacific Stars and Stripes, a newspaper of the American armed forces. After completing his military service, Buell joined the AP in Chicago, working as a radio writer before moving to the New York picture desk in 1957. In 40 years with the AP, 23 of those as head of AP’s picture operations, Buell saw ways in which technology could be used to serve AP’s needs for faster and better photo delivery systems. He envisioned and implemented the transition from Wirephoto, developed in 1935, to digital transmission, the end of the chemical darkroom, development of the first digital news camera in 1994, and creation of AP’s digital photo archive in 1997.

As technology changed, Buell continued to champion the central role of photography in reporting the news. He was AP’s second executive photo editor, succeeding Al Resch, who had held the post from 1938 to 1968. Interviewed at the time of his retirement in 1997, Buell reflected that the proudest moments of his AP career were not the technological innovations, but the 12 Pulitzers won by AP photographers while he was photo editor.

Hal Buell (center) AP's assistant general manager for news photos and Dave Herbert (seated), the consultant who wrote the electronic darkroom software, explain PhotoStream at the American Newspaper Publishers Association (ANPA) technical convention in Las Vegas, June, 1987. (AP Photo/Coporate Archives)

During ceremonies marking the 40th anniversary of East Germany, Soviet Premier Mikhail Gorbachev, left, kisses East German leader Erich Honecker at Schoenfeld Airport in East Berlin, East Germany on Oct. 6, 1989, shortly before Henecker was forced out of power, and a month before the fall of the Berlin Wall. (AP Photo/Boris Yurchenko)

A man sits atop the wall near the Brandenburger Tor (Brandenburg Gate), Nov. 10, 1989 in Germany as he chisels a piece of the wall that divided East and West Berlin. Thousands of East Berlin citizens came into the western part after the border opened, unifying East and West Germany. (AP Photo/Jockel Finck)

AP Flash reporting that the dismantling of the Berlin Wal had begun. (AP Photo/Corporate Archives)

“Look around you! History is changing everything.”

Alison Smale

The fall of the Berlin Wall on Nov. 9, 1989, is a story that began months earlier, in May of that year, when Hungary began taking down its border with Austria. AP staffers covered the story from Hungary, Austria, Czechoslovakia, Poland and Germany, filing copy and photos documenting the last days of the Iron Curtain.

Alison Smale, who was AP’s Vienna bureau chief and chief Eastern European correspondent in 1989, had been covering Soviet and European affairs for the AP since 1982. When the East German Communist Politburo resigned en masse on November 8, 1989, Smale boarded a plane for Berlin, knowing that the end of a divided Germany was imminent. Smale crossed into East Berlin and was watching the news from the press building in East Berlin, where AP had its offices, when an East German press officer made a premature announcement that East Germans would be allowed to travel freely to the west “ab jetzt”— from now on.

In a 2010 oral history interview for the Corporate Archives, Smale described how the story unfolded.

“…we’re watching on television and it’s really very boring and, and then all of a sudden right at the end he says his famous sentence…, which we now know was a mistake, I mean, it was a complete misunderstanding, that he should never have read it out at that time and he should never have said it took effect immediately—and it was just stunning…. and that’s how the Berlin Wall fell.

“…there was a wonderful Austrian guy who worked for the AP German services based in East Berlin. He said, “Come on, I mean, we’ve got to get out on the streets, man, and we’ve got to tell people,” and we—I said, “We’d better take the official agency report with us, because people won’t believe us …

Then West German television said, “Yeah, and we hear that—[wir hören das ist auch schon am] Checkpoint Charlie [geht]”—“We hear it’s all, already possible at Checkpoint Charlie.” I said, “Checkpoint Charlie? Jesus!” I mean, you know, that’s the symbol. So we raced there in a car, and we got there just as the first East Berliners were arriving as well….…And it was very clear that the border guards had absolutely no orders. They didn’t know what to do. …they sort of shoved me into this narrow little corridor and somehow this East German woman squeezed in with me and I remember she went “[Ja!]” like this and we went to the pimply youth at the end of the, other end of the corridor who was checking passports, and he looked at my passport and then he looked at her papers, and she somehow had permission to visit the West but not until the seventeenth of November, so this guy says, “But you know, it’s only valid on the seventeenth of November,” and I said, “[Schauen sie sicht auf um, man!]”—“Look around you!” History is changing everything. Who cares whether it’s the ninth of November {laughs} or the seventeenth of November, and he shrugged and pressed the button to open the door, and that’s how I think anyway I crossed Checkpoint Charlie with the first East German to cross that night.”

This Nov. 10, 1989 file photo shows Berliners singing and dancing on top of the Berlin wall to celebrate the opening of East-West German borders. Thousands of East German citizens moved into the West after East German authorities opened all border crossing points to the West. In the background is the Brandenburg Gate. (AP Photo/Thomas Kienzle)

A crowd estimated at 50,000 people brave a driving rain to gather in front of the Kremlin in Moscow on Sunday, July 16, 1990. After thousands of people staged their protest, President Mikhail Gorbachev announced his decision to open airwaves to groups other than the Communist Party. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko)

Russian President Boris Yeltsin dances at a rock concert after arriving in Rostov, Monday, June 10, 1996. A new poll gives President Yeltsin his biggest lead yet, over Communist challenger Gennnady Zyganov in the Russian presidential election. (AP Photo/Alexander Zemlianichenko)

A Chinese man stands alone to block a line of tanks heading east on Beijing's Cangan Blvd. in Tiananmen Square on June 5, 1989. The man, calling for an end to the recent violence and bloodshed against pro-democracy demonstrators, was pulled away by bystanders, and the tanks continued on their way. The Chinese government crushed a student-led demonstration for democratic reform and against government corruption, killing hundreds, or perhaps thousands of demonstrators in the strongest anti-government protest since the 1949 revolution. Ironically, the name Tiananmen means "Gate of Heavenly Peace". (AP Photo/Jeff Widener)

Nelson Mandela and wife Winnie, walking hand in hand, raise clenched fists upon his release from Victor Verster prison, Cape Town, Sunday, February 11, 1990. The African National Congress leader had served over 27 years in detention. (AP Photo)

“Wake up, Bob, the war’s begun!”

Edie Lederer

On January 15, 1991, correspondent Edie Lederer’s bulletin provided the first official word that the Gulf War had begun. Lederer, who was coordinating AP’s war coverage from Saudi Arabia, was in the military pool of reporters covering the airplanes that took off for Iraq and Kuwait. She was on the ground with David Evans of the Chicago Tribune when the first wave of Air Force fighter bombers took off.

Lederer told the story in the Spring, 1991 issue of AP World:

“David and I wanted to file immediately, but we had been told there were no commercial telephones at the base. We begged [Major Jerry] Brown to take us to the nearest town, about a 30-minute drive away. Otherwise, it would be hours, or even days, before our story got out.”

Overhearing the conversation was Col. Ray Davies, the base maintenance chief who Lederer had met during a previous visit. Davies came to the rescue, leading Lederer and Evans to a trailer on base, equipped with modular telephones.

“I picked up one, called the Dhahran International Hotel, where the AP had its headquarters, and asked for the office extension. When AP photo chief Bob Daugherty, who lived in the adjoining room, answered the phone sleepily, I realized David and I were about to scoop the world. 'Wake up, Bob, the war’s begun!’ I shouted.

By the time the war ended on February 26th, the AP had transmitted more than 4,000 stories and a steady stream of high-quality color pictures. Using new photo compression technology, pictures from the Gulf War were transmitted faster than in any previous conflict.

A Kuwaiti oilfield worker kneels for midday prayers near a burning oil field close to Kuwait City on Saturday, March 2, 1991.The fires, apparently set by retreating Iraqi soldiers, continue to burn out of control throughout Kuwait. (AP Photo/Michael Mipchitz)

Gov. Bill Clinton, sitting in with the band, turns out an impressive version of "Heartbreak Hotel," as Arsenio Hall gestures approvingly in the musical opening of "The Arsenio Hall Show" taping at Paramount Studios in Hollywood, June 3, 1992. (AP Photo/Reed Saxon)

The AP collaborated with Kodak in 1994 to develop the NC-2000, the first digital camera used by AP photographers. It cost $14,500 and boasted a removable storage drive that could hold 75 images.

According to the AP news release of Feb 8, 1994, the News Camera 2000 (NC2000) was "the first electronic camera designed specifically to meet the news photographer's need for speed, portability, and quality." This early digital camera was developed jointly by Kodak and the Associated Press. Based on a Nikon body, the NC2000 was the first digital camera to gain widespread acceptance as a primary camera among news photographers. (AP Photo)

Brochure announcing the launch of AP's video news business, APTV, in London, 1994. (AP Photo/Corporate Archives)

Front page of an advertising brochure for The Wire, the Associated Press news website, 1996. (AP Photo/Corporate Archives)

In this Nov. 24, 2000, file photo, Broward County, Fla., canvassing board member Judge Robert Rosenberg uses a magnifying glass to examine a disputed election ballot at the Broward County Courthouse in Fort Lauderdale, Fla. Two decades ago, Florida's hanging chads became an unlikely symbol of a disputed presidential election. This year, the issue could be poorly marked ovals or boxes. (AP Photo/Alan Diaz)

The 2000 presidential election is the only election since 1848 which the AP has not called. On Dec. 12, 2000, in the case of Bush v. Gore, the Supreme Court reversed a Florida Supreme Court’s order to recount the state’s ballots, forcing the recount to end. Lacking a final tally, there was no way for AP to determine a winner.

.

Text and photo editing by Francesca Pitaro, AP Corporate Archives.