Victory: Commemorating the 75th Anniversary of the End of World War II

“’Victory’ is a primary source: realtime broadcasts, diaries, dispatches, and other firsthand accounts of the amazing events as they unfolded. As a primary source, the book has special meaning because of the significance of the stories that it tells: of history’s greatest and most destructive war; of the epic clash of right and wrong; of the transformation of America, which in the span of this book rose from eminence to preeminence.”

--David Eisenhower

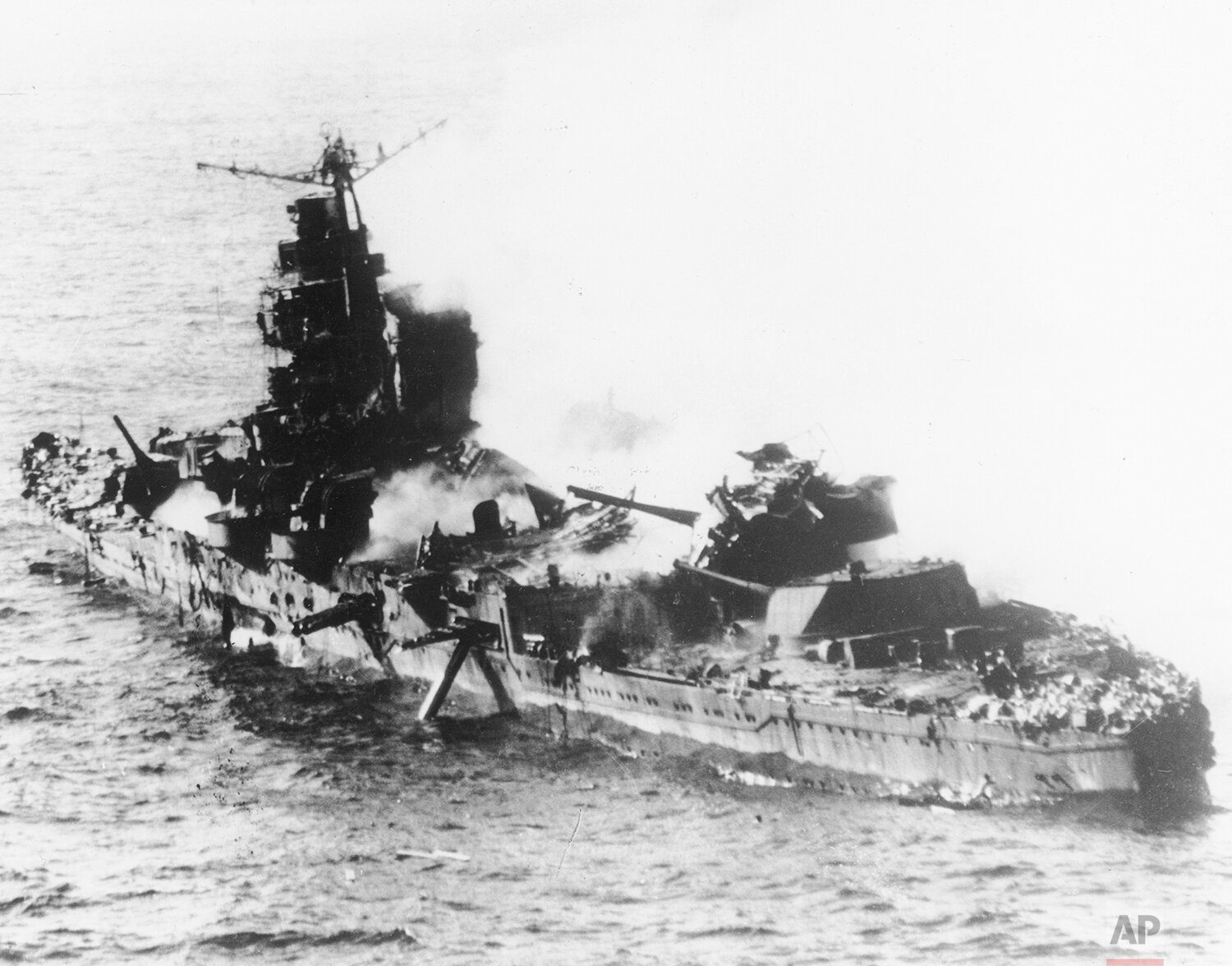

On this Veterans Day, The Associated Press is pleased to feature a new book from Sterling Publishing called “Victory: World War II In Real Time,” which features original articles and photography by AP journalists as reported throughout to commemorate more than 60 key events of the war from 1939 to 1945.

The following is from the Preface:

U.S. Marines of the 28th Regiment, fifth division, cheer and hold up their rifles after raising the American flag atop Mount Suribachi on Iwo Jima, a volcanic Japanese island, on Feb. 23, 1945 during World War II. (AP Photo/Joe Rosenthal)

Reporting the War

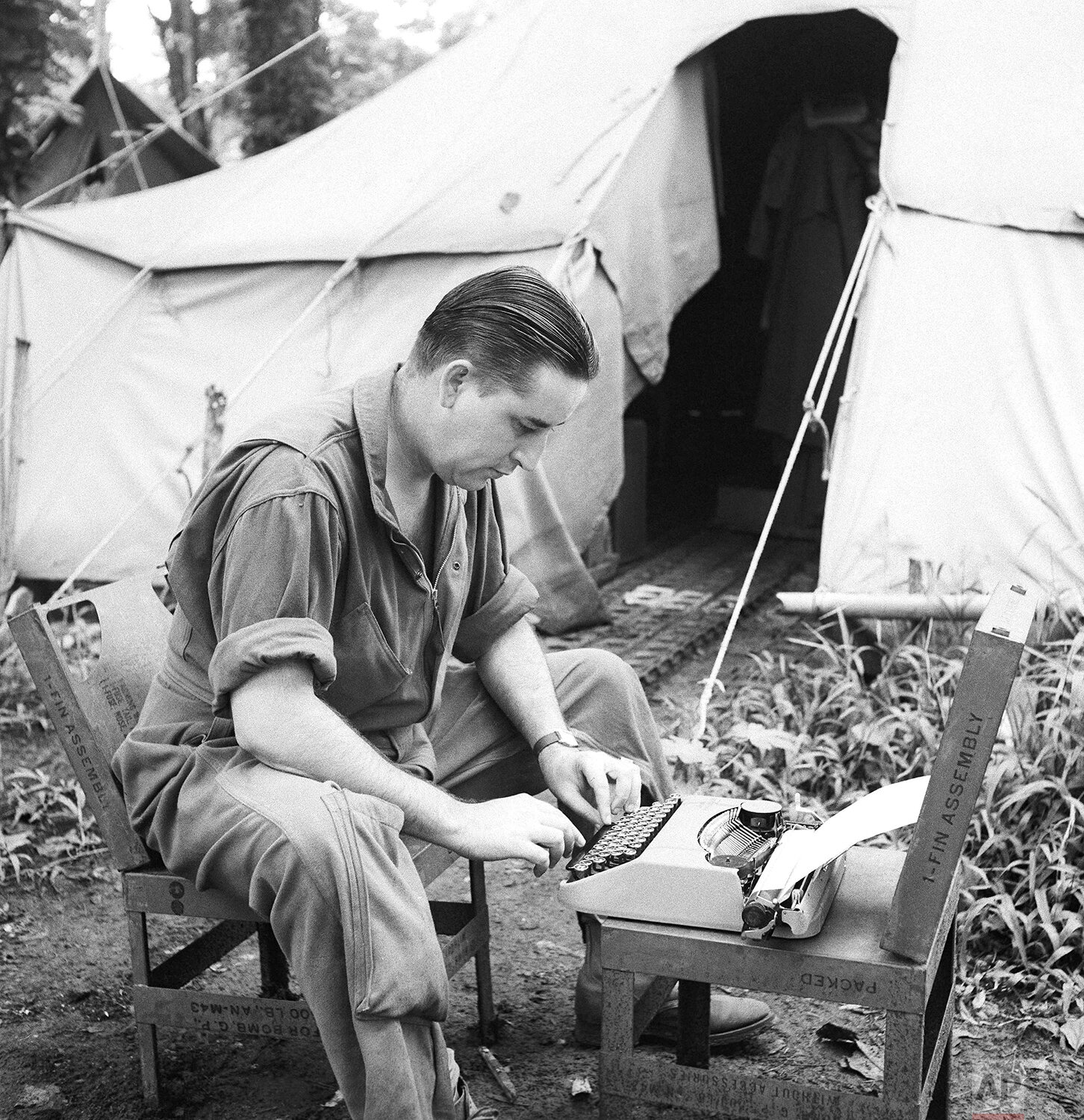

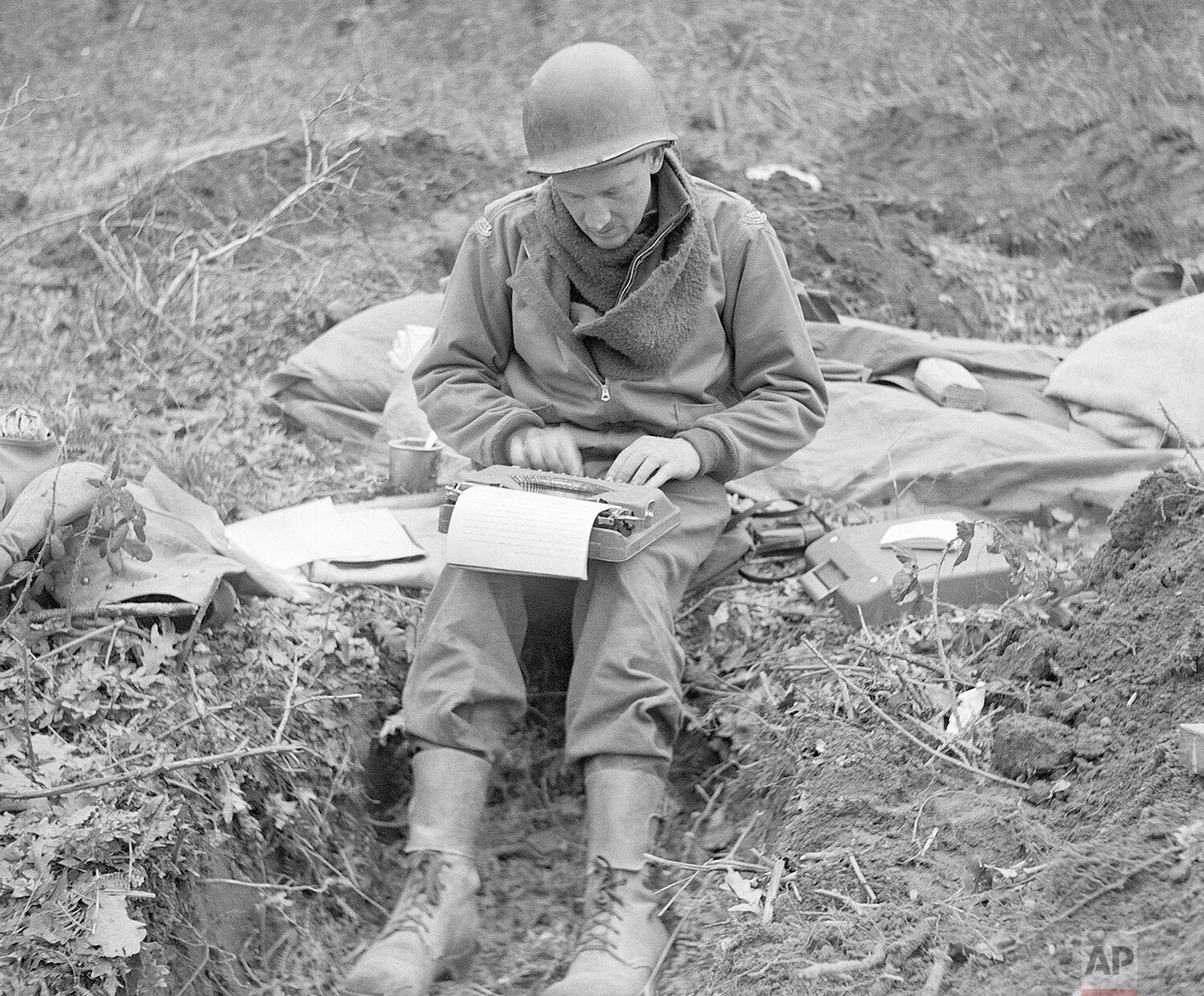

Herewith is the epic story of World War II: the story that civilians on the home front read day by day in their newspapers as reported by war correspondents and photographers of The Associated Press.

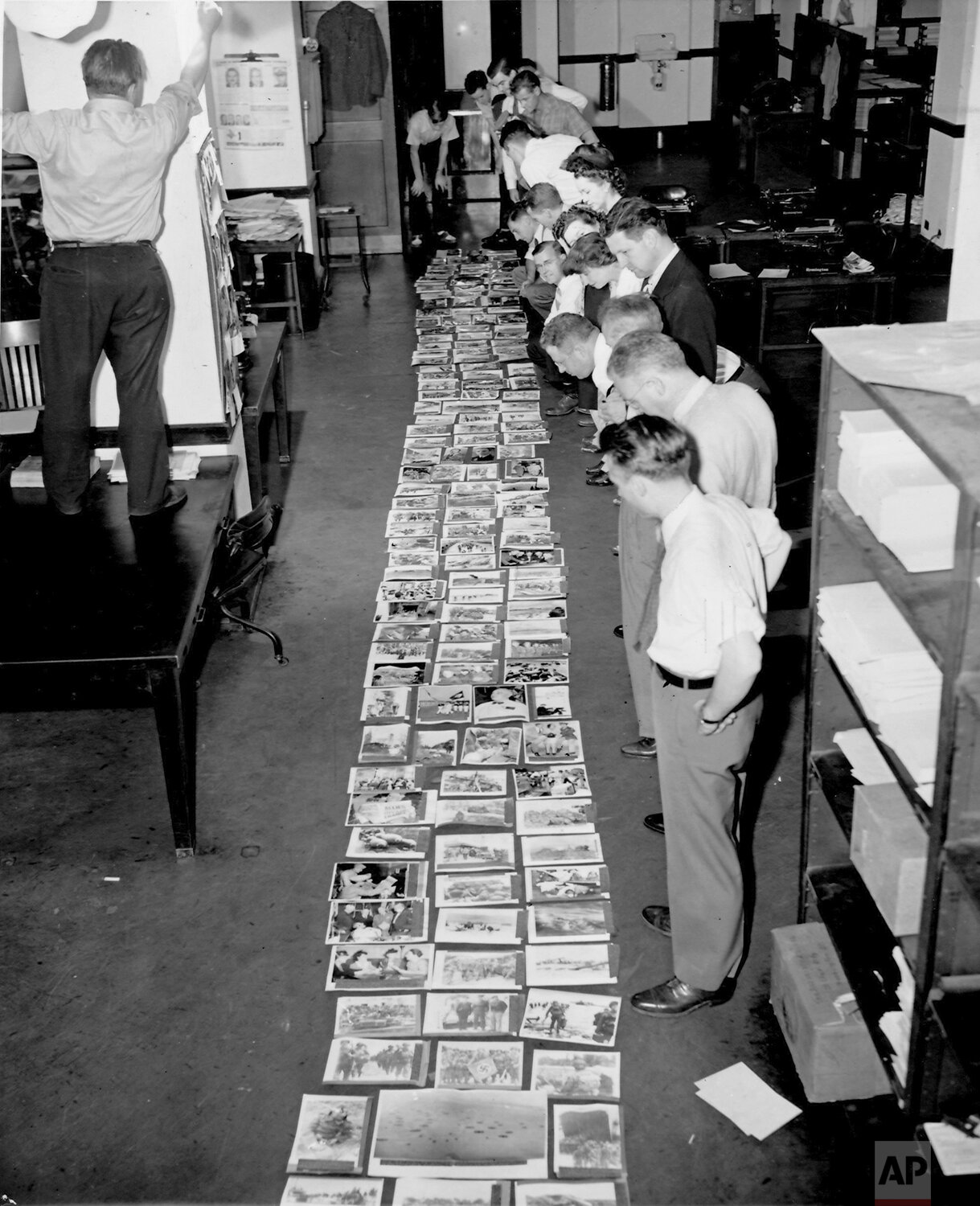

At the outset of this project, historian Alan Axelrod provided us with an out-line of important, pivotal events in the war, which I used to compile the articles from wartime newspapers that make up the bulk of this book. While pulling the articles, I was struck by the fact that the historical outline and the newspaper stories often differed (something I was aware of intellectually, but never realized to what degree until working on Victory); some of the stories hardly made the papers at the time of the events. This wasn’t poor journalism, it was wartime journalism, and it was done that way for a good reason—which is a story in itself:

On Jan. 15, 1942, a month after America’s entry into the war, a Code of Wartime Practices for the American Press was issued by the Office of Censorship, and in June of that year, the U.S. Office of War Information (OWI) was created. Together, these developments set forth guidelines for the content of the news that stated that no coverage of the war should benefit the enemy. The code noted that “the security of our armed forces and even of our homes and liberties will be weakened. . . by every disclosure of information”—be it related to the activities and identities of Allied troops or even weather reports that covered more than four adjoining states outside of a 150-mile radius—for fear that such disclosures might facilitate enemy military operations. In general, the news was supposed to accentuate the positive and minimize the negative both for the sake of GIs on the battlefront and for civilians on the home front consuming war news.

These news-reporting guidelines, for the large part, were voluntary, heavily relying on reporters’ and editors’ patriotism. Among the concessions were delaying battle reportage for 24 hours, eliminating casualty counts and banning photographs of Allied war dead, censoring troop movements, and maintaining confidentiality of the whereabouts of important Allied leaders, including Gen. Dwight D. Eisenhower, President Franklin D. Roosevelt, and Prime Minister Winston Churchill. Other provisions ranged from the very specific, such as not reporting factory out put, to the broadest, including handling the obvious—and not so obvious—enemy propaganda aimed at GIs and the folks at home.

While the accuracy of the news was a concern for all, it was fortunate that at its forefront was one of America’s top journalists, Byron Price, the executive news editor of The Associated Press and the pre-war head of its Washington news bureau. Twelve days after Pearl Harbor, Price was appointed by President Roosevelt’s administration as the U.S. Director of Censorship. He quickly established advisory panels in an effort to reasonably balance news reportage without misleading the public, including administering newspaper and radio codes of conduct.

In 1944, Price earned a special Pulitzer Prize for his diligence and was later presented the Medal for Merit by President Harry S. Truman in 1946 for his wartime efforts.

The day after the Japanese surrendered on Aug. 14, 1945, Price happily hung a sign in front of his censorship office that read: “Out of Business.”

—Les Krantz, Producer and Developer

In this May 7, 1945 photo, British civilians and Allied service men and women gather, as part of a huge crowd, outside Rainbow Corner, the American Red Cross club, near Piccadilly Circus, London to hear the final announcement of Germany's surrender in World War II. (AP Photo)

“Victory: World War II In Real Time” is available at Amazon and wherever books are sold.