We're Taking Fire: A Reporter's View of the Vietnam War, Tet and the Fall of LBJ

On the 50th anniversary of the Tet Offensive comes “We’re Taking Fire: A Reporter’s View of the Vietnam War, Tet and the Fall of LBJ” by former AP war correspondent and Pulitzer Prize-winner Peter Arnett. This powerful account revisits Arnett’s coverage of the Vietnam War, examining what led to the surprise attack that began in the early hours of Jan. 31, 1968 and became a turning point of the war, and the turbulent aftermath.

An eyewitness to the battles, maneuvers and cultural challenges that prevented a definitive victory, Arnett explores the complexities that drove the decisions made by the Eisenhower, Kennedy, Johnson and Nixon administrations and how each was unable to achieve a winning strategy that would put an end to the unpopular war.

Arnett, who reported on the Vietnam War for AP from 1962 until its end in 1975, offers a unique perspective that only someone who was on the ground can share, as well as sharp analysis shaped by observing U.S.-Vietnam relations in the decades after the war.

The following is an edited excerpt.

TET ’68: THE FIRST 36 HOURS

The blast of strings of exploding firecrackers jerked me awake as Vietnamese neighbors continued their celebrations into the early hours of the morning. It was Saigon, January 31, 1968, the first day of the year of the traditional lunar calendar, Tet Nguyen Dan, and the most important Vietnamese festival. Amid the cacophony I noticed a loud, methodical rat-tat-tat that shook our apartment shutters as though someone was banging on them with a hammer. I’d heard that sound before in the battlefield, the roar of a heavy-caliber machine gun, and it seemed to be shooting up Pasteur Street just three room-lengths away. A weapon that lethal had not been discharged in Saigon since the overthrow of President Ngo Dinh Diem four years earlier.

I opened my bedroom window and watched as war came to Saigon from the jungles and paddy fields and peasant villages where it had lingered for years. Red tracer bullets zipped through the sky and firefights were erupting near the centers of power in South Vietnam’s capital, the presidential palace and the American embassy. As the sounds of exploding grenades and rockets vibrated through the darkness, I bundled my wife Nina and my young children, Elsa and Andrew, and our maid into the bathroom, which I hoped was safer than the rest of our small apartment, and I covered them with mattresses from the beds. I phoned the Associated Press office, and bureau chief Robert Tuckman answered, his voice high-pitched and excited: “They’re shelling the city, for God’s sake.” I told him I was on my way.

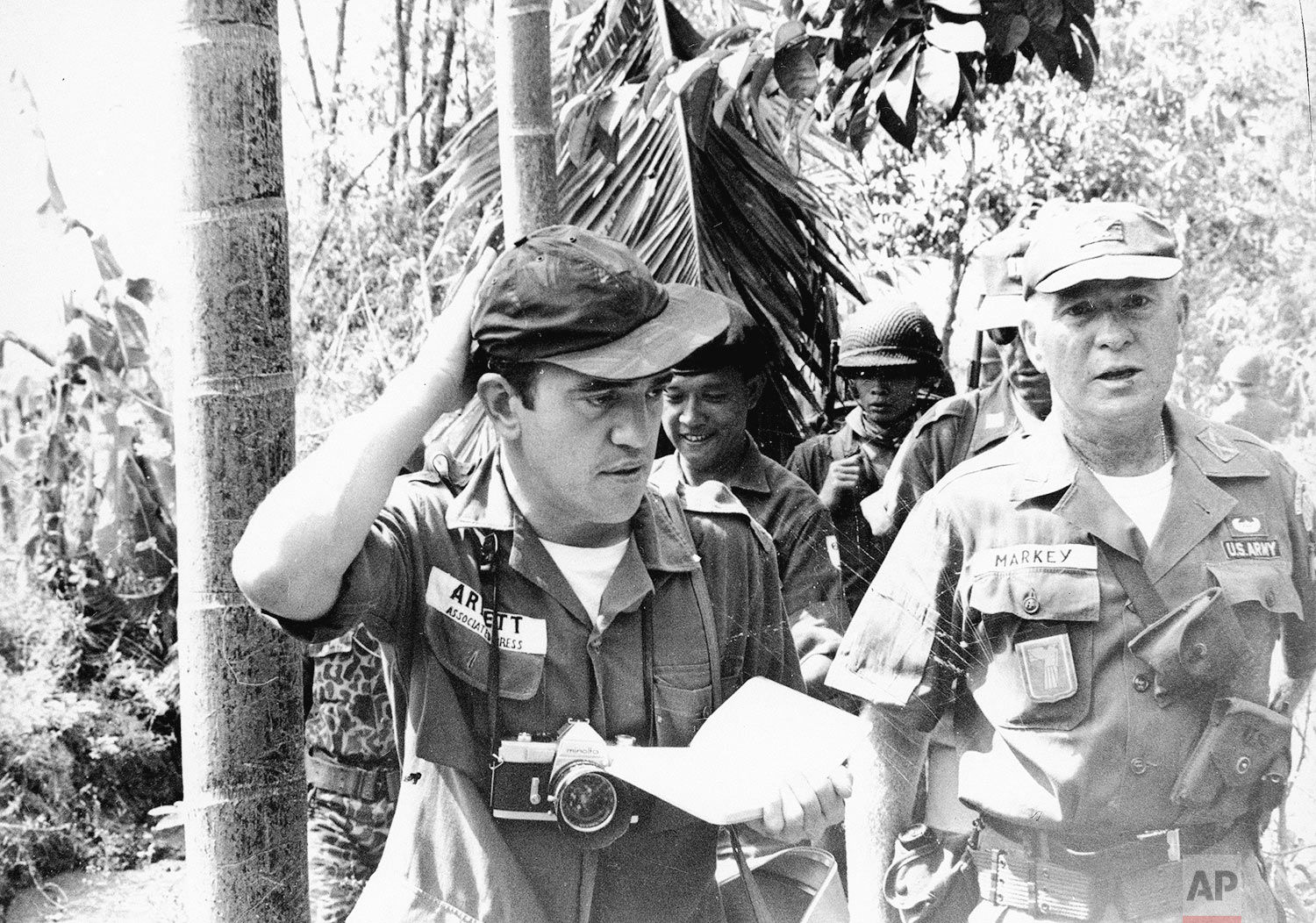

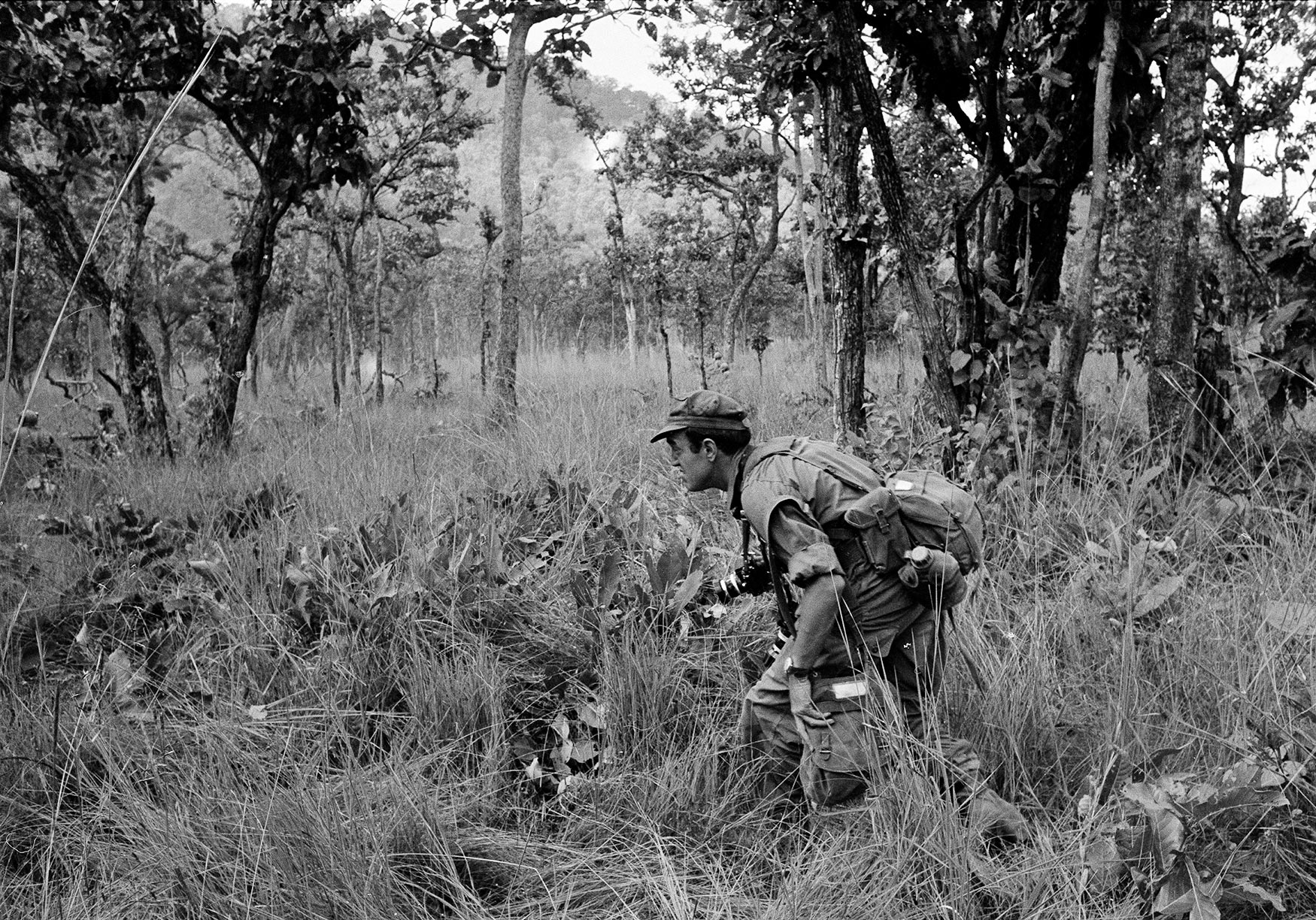

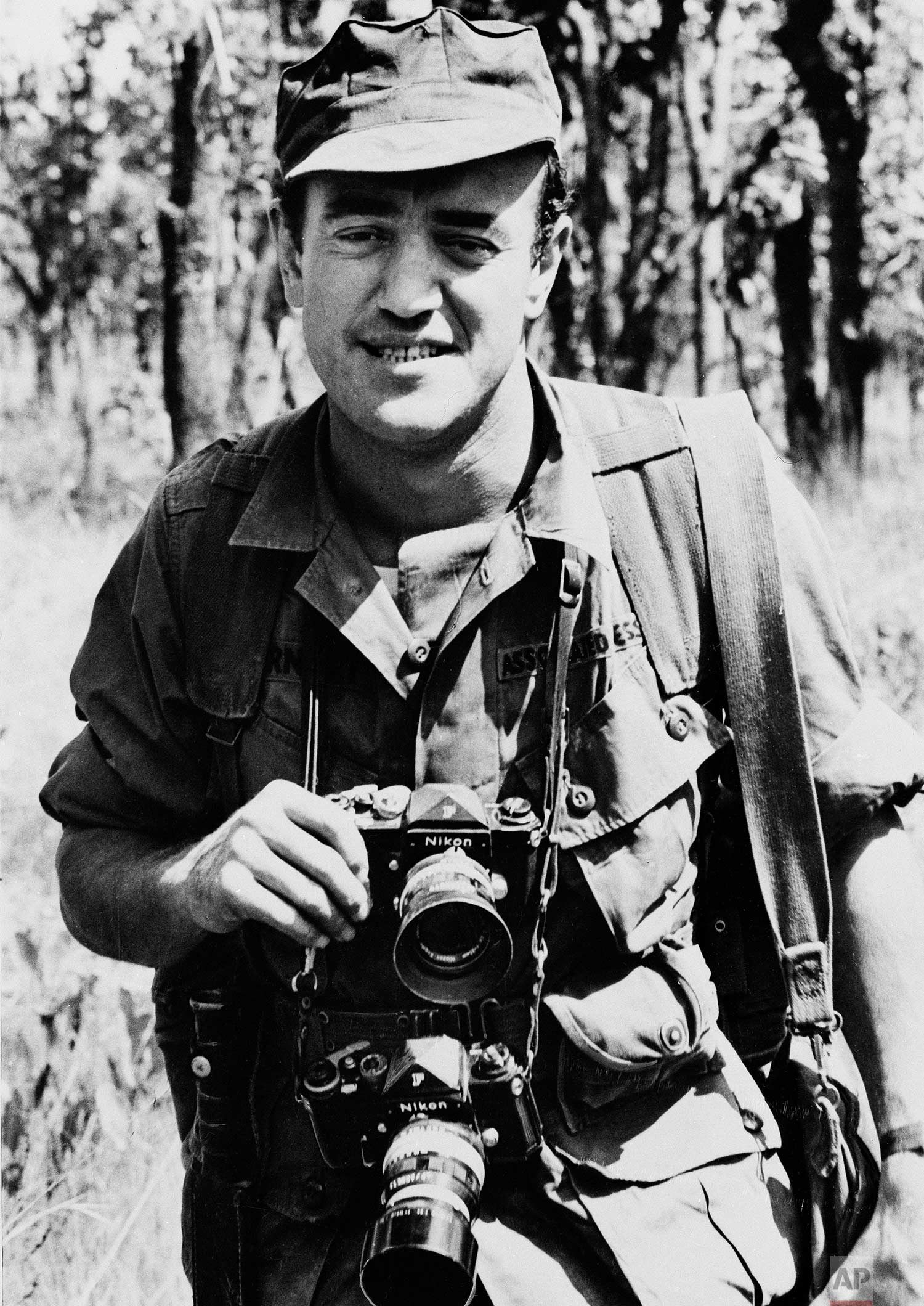

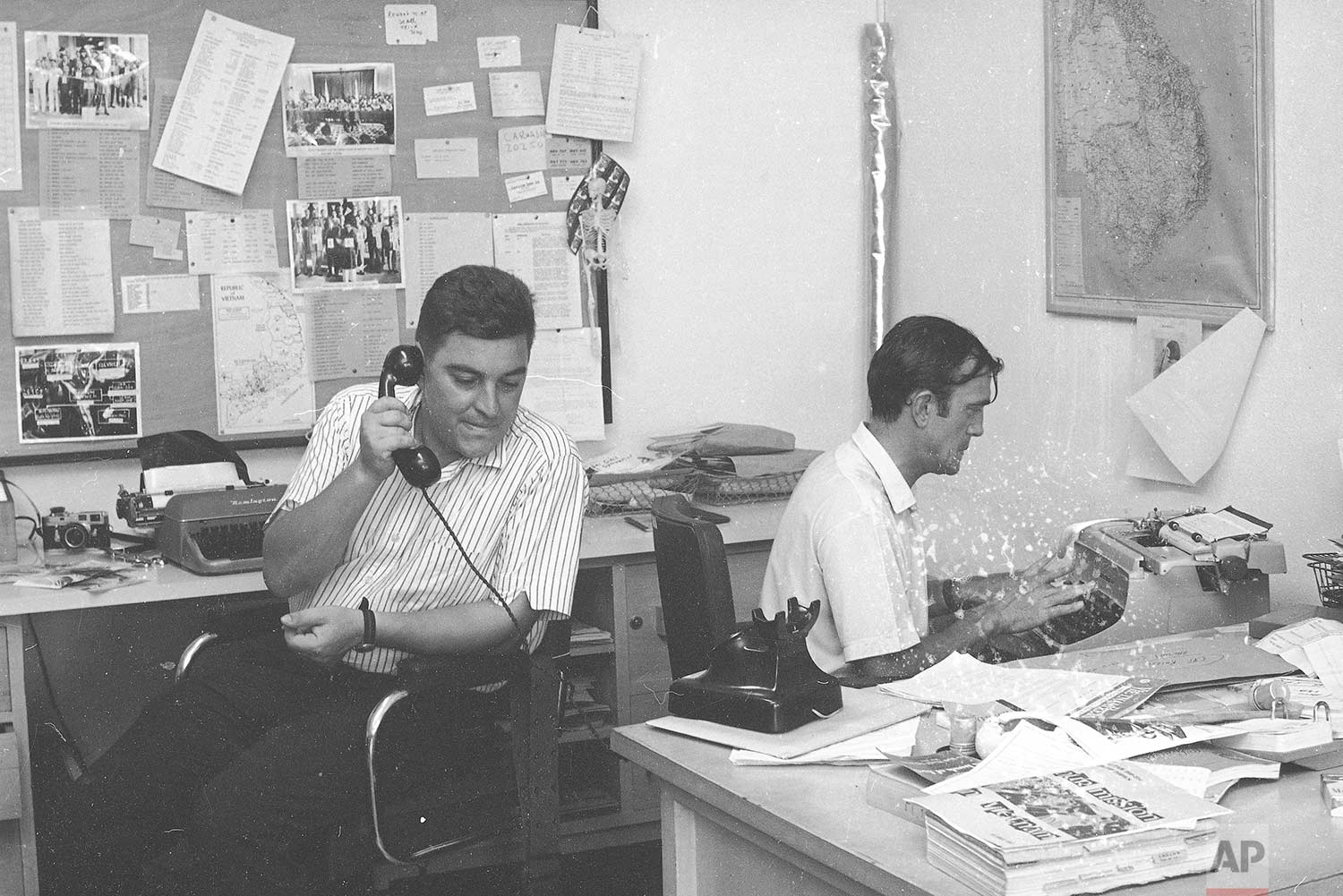

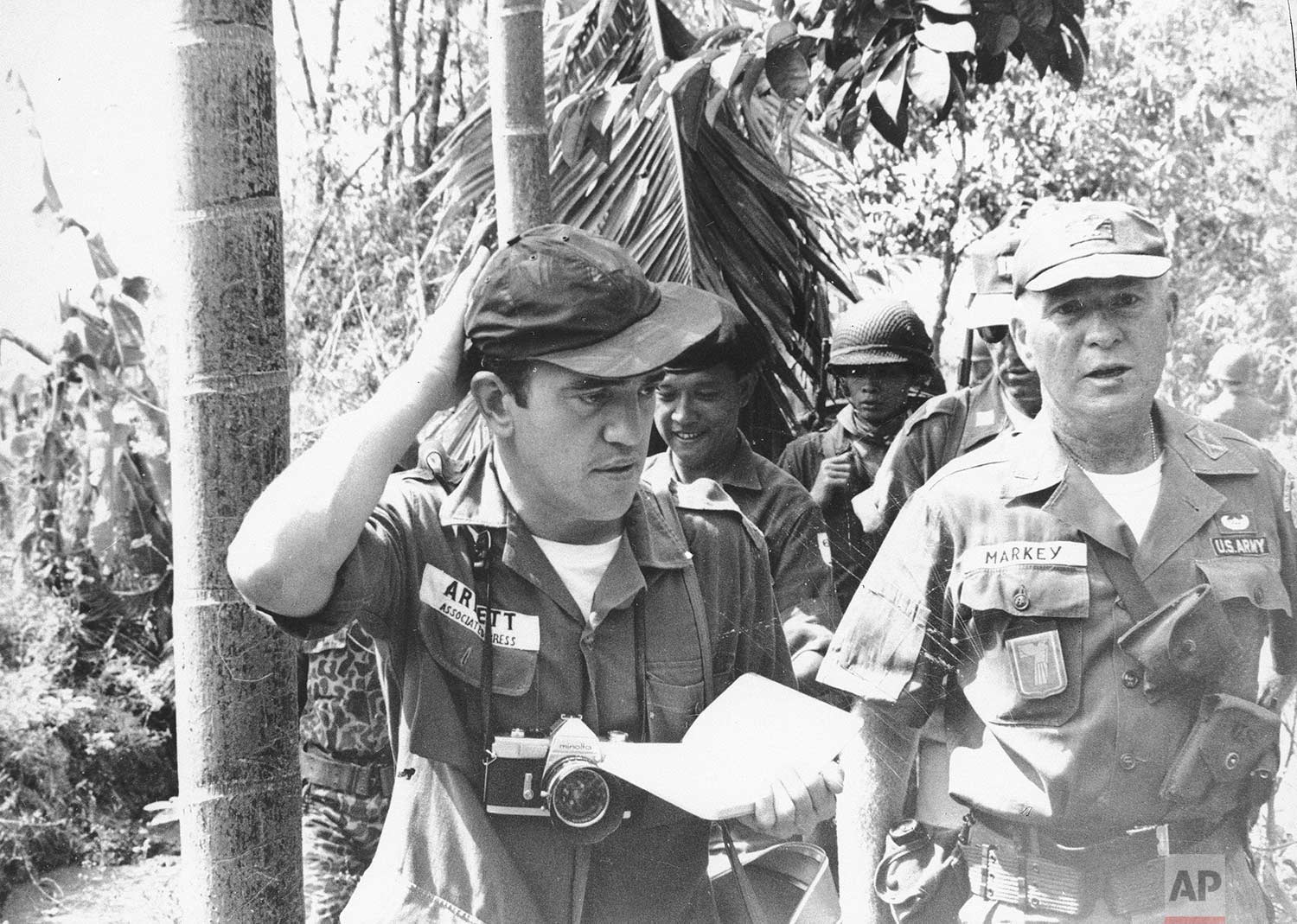

AP journalist Peter Arnett

I wasn’t the only one so rudely awakened in total surprise at around 2:30 that morning. Only those in the know -- the attacking Vietcong guerrillas and North Vietnamese military forces and their allied clandestine networks in the city -- had any idea of what was happening. By quietly moving combat troops through the supposedly secure countryside into the heart of Saigon, they were able to strike without warning. General William Westmoreland, the increasingly confident commander of all American combat forces fighting in Vietnam, was asleep in his comfortable villa at Tran Quy Cap street when attacks began all around his neighborhood.

AP journalist Peter Arnett

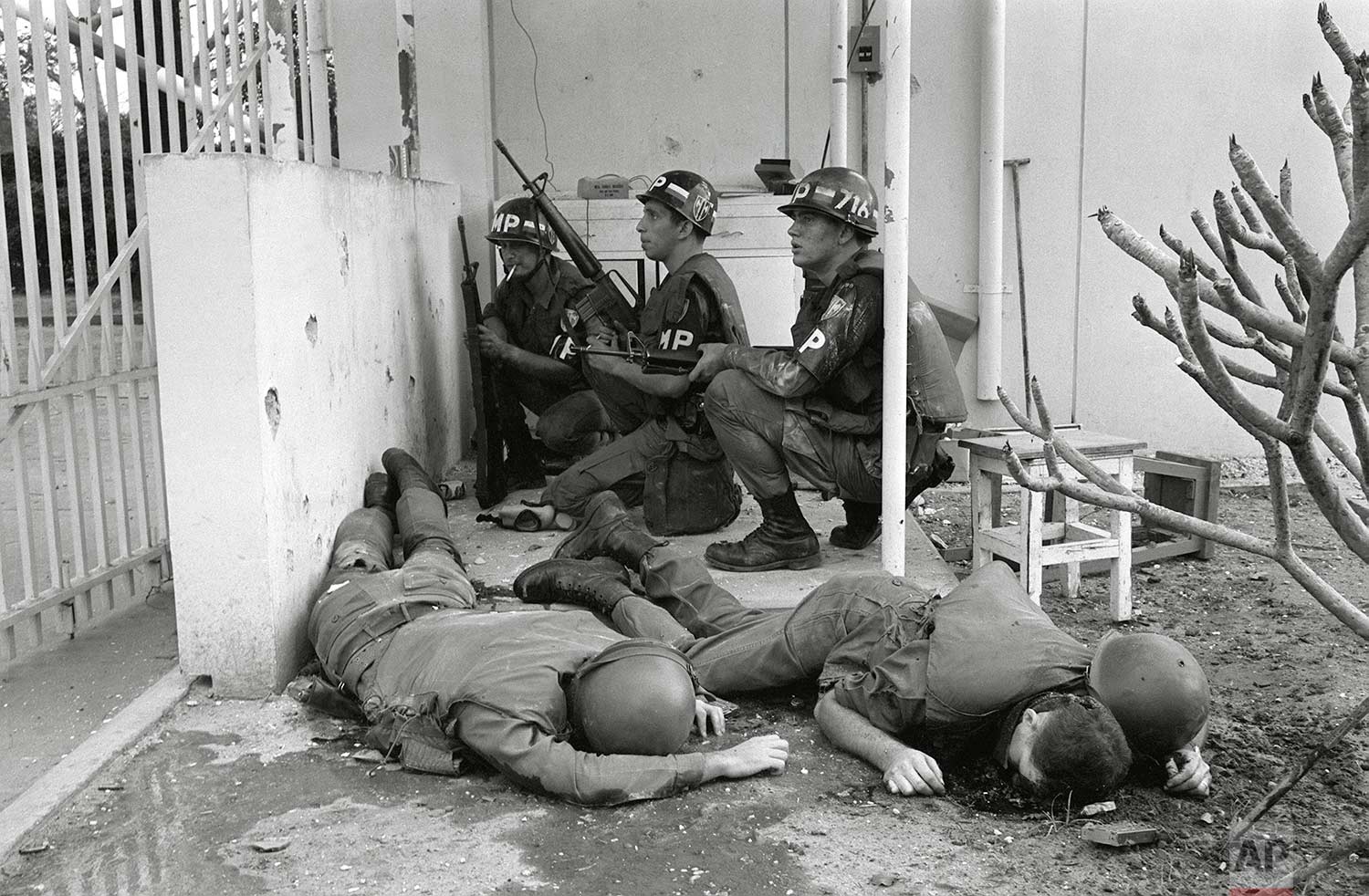

Just nine weeks earlier, the general visited the United States on the orders of President Lyndon Johnson to participate in a “success offensive,” a concerted effort to bolster public support for the war. In an address at the National Press Club, he asserted that the Vietcong were “unable to mount a major offensive” and that the point was reached “when the end begins to come into view.” But on this early morning, Westmoreland was stuck, unable to reach his Saigon headquarters as gunfire roared in the street outside. By telephone, he learned of the spiraling crisis, particularly a fierce attack on the six-story American embassy at Thong Nhut street several blocks away. He later said, “My Marine aide was talking to the Marine guard inside the embassy, and by my numerous telephone conversations with U.S. Army MP command I was able to follow the course of the battle and direct action.”

Ambassador Ellsworth Bunker was similarly blindsided by the ferocity of the enemy attacks, particularly the assault on his embassy. He was asleep in his villa four blocks away when his security team rushed into his bedroom and ushered him down to the basement in his pajamas. Wearing his bathrobe, he was soon loaded into an armored car and driven to a safe house. Bunker had been in South Vietnam less than a year, and in that time, he had worked closely with Westmoreland and endorsed his views.

AP journalist Peter Arnett