Veterans are more likely than most to kill themselves with guns. Families want to keep them safe.

She leaned out of the tent at a small-town summer festival, hoping someone would stop to ask about her tattoos, her T-shirt, the framed pictures of her son on a table in the back of the booth.

Barbie Rohde has made herself a walking billboard for this cause. She feels called to say the words, as much as they sometimes rattle the people who stop at her booth: “veteran suicide.”

A man in an Army cap recoiled and walked away. His wife said she was sorry, he suffers from post-traumatic stress disorder and struggles to speak of it.

“I worry for him and for us every day,” she said.

Rohde reached underneath her display tables, grabbed a gun lock and wrapped it in a blue bandana, printed with the phone number for the Department of Veterans Affairs crisis line: call 988, press 1.

“Here’s some free goodies for you,” she said, and tucked it discreetly into the bag with two T-shirts the woman bought.

Rohde runs the most active chapter of a nonprofit called Mission 22, aimed at ending the scourge of military and veteran suicide, which kills thousands every year, at a rate far higher than the general population. Three-quarters of those who take their own lives use guns.

One of them was her 25-year-old son, Army Sgt. Cody Bowman.

For decades, discussions of suicide prevention skirted fraught questions about firearms, experts say, and the Army has not implemented measures that might be controversial. But a growing conviction has taken hold, among researchers, the VA, ordinary people like Rohde: If America wants to get serious about addressing an epidemic of suicide, it must find a way to honor veterans, respect their rights to own a gun, but keep it out of their hands on their darkest days.

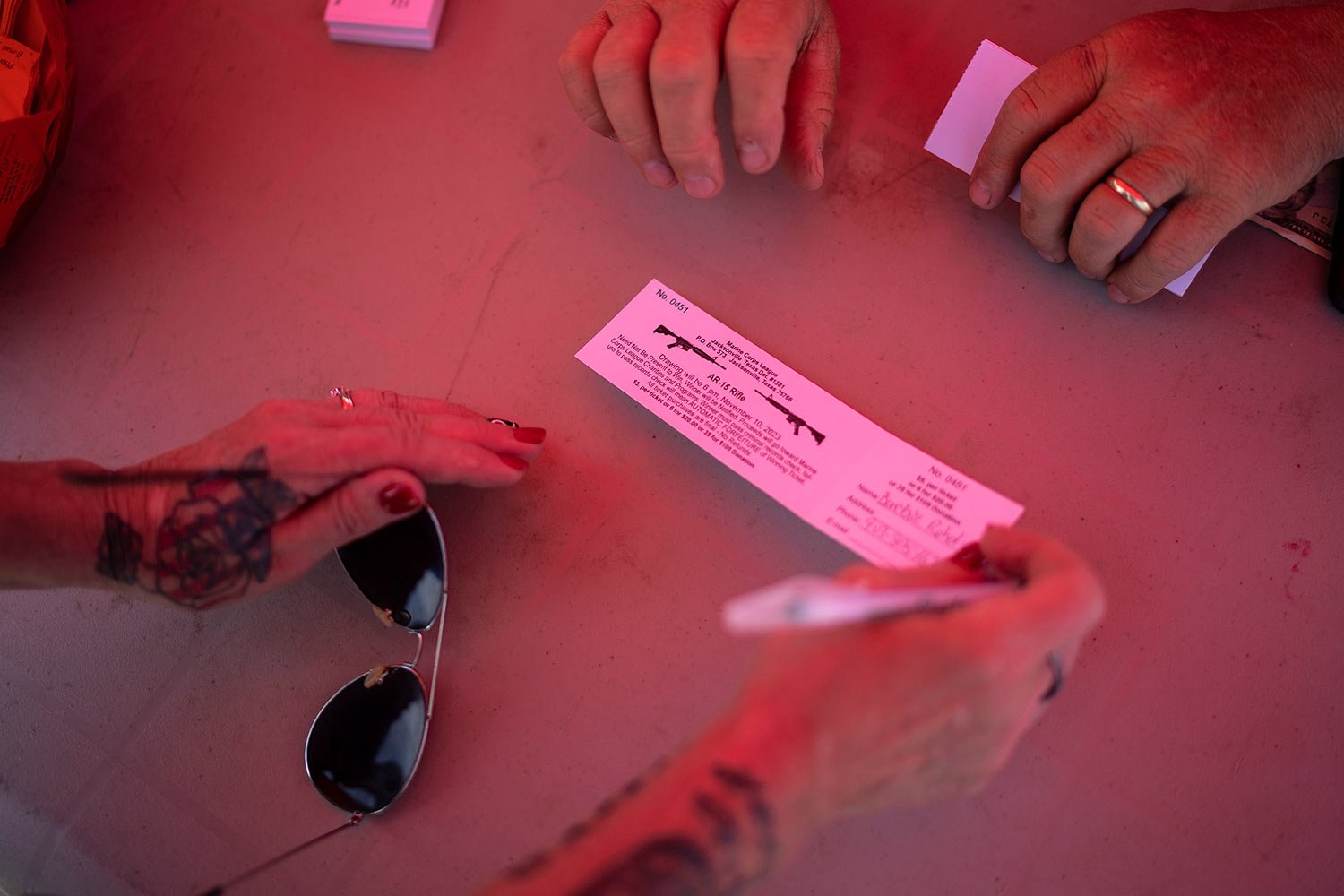

Barbie Rohde buys a raffle ticket to win an AR-15 rifle at a festival while volunteering for Mission 22, a nonprofit that is focused on ending military and veteran suicide, Saturday, June 10, 2023, in Jacksonville, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

A boy reaches up for a toy machine gun for sale at a festival Saturday, June 10, 2023, in Jacksonville, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Rohde travels to towns all over conservative, gun-loving east Texas. At this festival, the Marine Corps booth down the street was auctioning off an AR-15 to raise money for a children’s charity. She passed a toy booth, where a popular item was a plastic version of the rifle. She stopped to visit a friend who hands out free gun locks to anyone who buys his T-shirts, some supporting former President Donald Trump, others that declare: “God. Guns. Coffee.”

This is a place where people believe deeply in the Second Amendment, that guns are fundamental to the identity of the nation, that guns protect their families. And Rohde believes that, too — except, sometimes, the tool you thought would protect you might be what destroys you.

She tells her story to anyone who will listen: She had been worried about her son. Most of his left hand had been blown off in a training accident. He told his mom he didn’t know if he could continue his military career, and all he’d ever wanted to be was a soldier. He asked for his guns, which she had been holding. She’d hesitated. But they were his, and this is Texas.

Then one day, she got home from work waiting tables. She heard a car, looked out the window and saw men in military dress uniforms heading toward her house.

“Your son Sgt. Cody Bowman died of a self-inflicted gunshot wound,” they said. For the rest of the day, Rohde sat on the floor and screamed.

She didn’t eat for six days. She decided she wanted to be with her son.

She sat on her couch, crushed up sleeping pills, put them in a Blue Moon and drank it down. She guesses that subconsciously she didn’t want to die because she called a friend, who alerted her husband and she woke up in the hospital.

So when people say that if a person doesn’t have a gun, they’ll find some other way, she disagrees. She tried, and she lived.

Her son didn’t get that second chance.

Now her life is consumed with this volunteer work, so that when she visits her son’s grave, she can whisper all the things she’s done in his name, to spare another mother this agony, to make him proud of her.

“I’m glad I didn’t have a gun. Because if I would have had a gun, I believe I’d have finished the job. I need to be here, I still have a lot to do,” she said.

“And I wish Cody wouldn’t have had a gun.”

Barbie Rohde holds a photo of her son, Army Sgt. Cody Bowman, at her home Sunday, June 11, 2023, in Flint, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Barbie Rohde is a conservative, a devoted fan of Trump. She doesn’t like phrases like “gun control” and doesn’t believe in mandated gun restrictions. But something more needs to be done, she thinks.

“I truly believe that having such ready access to weapons is a big problem, the easy access for our military who are suffering,” she said. “That’s not a popular opinion for me to have. And I don’t care because that’s what I believe.”

Others believe this now, too.

The VA invited Joe Bartozzi, the president of the National Shooting Sports Foundation, to speak to health care providers at a conference on suicide in 2020. Bartozzi was nervous. He worried things might devolve into the heated debates he’s gotten used to: either guns are bad or guns are great, and there’s nothing in between.

But that didn’t happen. The doctors really wanted to know about firearms, how to talk to patients without it sounding like a gun grab — and what the industry could do to help.

“It’s a big change for us to be talking so directly about firearms,” said Matt Miller, who runs the VA’s suicide prevention efforts. The data had become too obvious to ignore any longer: the vast majority of people who attempt suicide do not die. A tiny fraction, only about 5% of people attempting suicide, use a gun. But guns are deadly almost every time, and so end up accounting for over half of suicide deaths. For veterans, that jumps to 75%.

Experts say that traumatic experiences at war play a role in veterans having a suicide rate 1.5 times higher than others. Yet even those with no combat history die by suicide at a much higher rate. What they have in common, researchers say, is demographics that are especially vulnerable to suicide: predominately white men with access to and a familiarity with firearms.

The military tasked a panel of researchers with recommending solutions. In February, that committee issued a 115-page report, including gun-safety measures like waiting periods on military property and raising the minimum age for servicemembers to buy guns to 25.

“We’re not trying to take people’s guns, we’re trying to prevent people from killing themselves,” said Dr. Craig Bryan, a veteran and Ohio State University psychologist who was on the panel. “I say it’s possible to value Second Amendment rights and also be willing to prevent suicide. Those two things can coexist.”

But the Defense Department punted on endorsing the gun restrictions, creating another panel to study them instead.

Gun suicides in the United States reached an all-time high last year, Johns Hopkins University found. The debate about guns usually centers on homicides and mass shootings, but suicides account for more than half of American gun deaths. Policy changes — like requiring permits, waiting periods, red flag laws — actually do more to prevent suicide than homicides, researchers say.

Robert Rohde mows the lawn past a fence adorned with pro-America signs at his home in Flint, Texas, Friday, June 9, 2023. This is a place where people believe deeply in the Second Amendment, that guns are fundamental to the identity of the nation, that guns protect their families. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

The biggest misconception, Bryan said, is that guns aren’t the problem. If someone doesn’t have a gun, people assume, they will find another way to end their life.

Suicide is an impulsive act. Research has shown that three-quarters of people move from thought to action within an hour. For 24%, it’s less than five minutes.

“And what they reach for is the greatest predictor of whether they will live or die,” Bryan said. Intentional overdoses, for example, end in death in 2% of attempts — it is slow, there is time to get help. Suicidal people, given a chance to change their mind, usually do, Bryan said.

When the District of Columbia put barriers on a bridge many jumped from, some scoffed: there was another bridge in eyesight, people would just jump there instead. But they didn’t. Bridge suicides dropped to almost nothing. In the United Kingdom, a particular drug became a common way people killed themselves. Lawmakers mandated a change in the packaging, making it more time-consuming to open. Suicides plummeted.

Bryan calls it “strategic inconvenience.”

The VA is now working with Bartozzi’s gun lobby; they set up suicide prevention booths at gun shows, encourage gun shops and ranges to offer to store firearms in a time of crisis, encourage responsible storage at home — anything Bartozzi said, to “put distance between the thought and the trigger.”

That’s why Barbie Rohde sneaks gun locks into her customers’ bags. A representative from the VA told her that they met a soldier who had decided to end her life and went for her gun. But it was locked. By the time she found the key, the impulse passed. She decided to stay alive, and the military officers did not have to knock on her parents’ door to repeat the horrible script Rohde endured.

But in Kingsport, Tennessee, the Fox family heard the car pull into the driveway.

Pictures of Army Sgt. Cody Bowman, bottom left, decorate the walls of Barbie Rohde's home in Flint, Texas, as she stands in her bedroom Friday, June 9, 2023. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

“Your son, Parker Gordon Fox, was found dead at his home this morning from an apparent self-inflicted gunshot wound,” they said.

His mother screamed.

“Not my child! Not my boy! Not my baby!”

When he was a kid, he pretended to be a superhero. He’d tie a blanket around his neck as a cape. He was 4 when his little brother was born, and he greeted them at the car, holding out another cape to put on the baby.

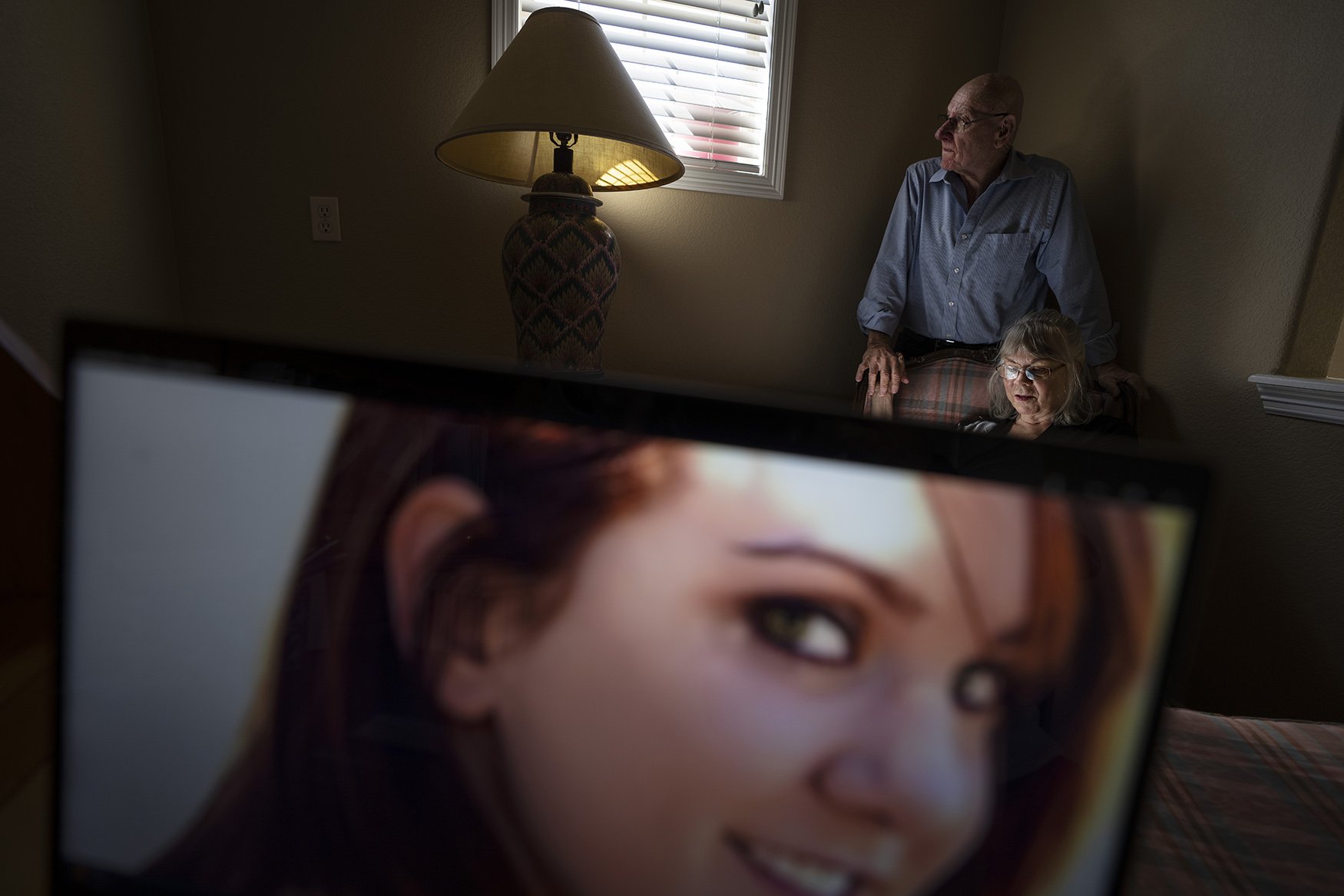

He was tiny for a long time. When he started high school, he wasn’t yet 5-feet tall and weighed less than 100 pounds. He was well-loved, and his friends defended him from bullies. His parents, Brenda and David Fox, wonder if that’s what drew him to the military: once he grew big and strong, he needed to defend others like he had been defended.

Parker was 19 when he told his parents he wanted to join the Army, in 2014, and his mother tried not to let him see her cry.

As the years went by, he told his parents about military colleagues taking their lives. They asked him if he was OK. And he’d say, “I have bad days, but everyone has bad days.” And that sounded like the answer they’d expect.

In 2020, they didn’t get to see him much because of COVID restrictions. He was a sniper trainer, based at Fort Moore, formerly Fort Benning, in Georgia, about six hours away.

He got leave in July 2020 and visited for a weekend. People have asked his parents if they now believe he came to say goodbye. But he was talking about his future, leaving the military, going back to college, buying a house. He left Sunday afternoon and his dad texted him a joke about the beer he’d left in the fridge: grapefruit flavored. I wish you would have left better beer behind, his dad said, and Parker responded with laughter.

He was already out drinking with friends, they’d later learn. That night he wrecked his car, with a friend in the passenger seat. No one was hurt, but he was drunk and felt ashamed. He told his friend, “I could have killed you.” He went home and kept drinking.

“It’s not like a person like him is vulnerable all the time,” his dad said. “They’re vulnerable during those low, low, low moments.”

His roommate found him dead in his bathroom. He was 25.

He left a note.

It started out tidy, then the handwriting grew more frantic.

“I have to do this quick because I have a lot of friends who would stop me.”

That’s the part that gutted them the most: It had to be fast, or someone would have saved him.

“If he didn’t have that gun would he still be with us? Absolutely,” his mother said. “I believe that down in my soul. He would have gotten through until the morning and he would have said, ‘God, that was a bad night but I’m here today and let’s go.’”

A relative called to ask: “What are you telling people?” There was an implication: this was shameful, this should be hidden.

Tell people the truth, they said.

“There was never shame. I’m so proud of my son, of the boy and the man he was. I don’t have one ounce of shame in him. I have regret,” David Fox said.

Robert Rohde has a cup of coffee before heading to a festival at sunrise with his wife, Barbie, to volunteer for Mission 22, a nonprofit that is focused on ending military and veteran suicide, Saturday, June 10, 2023, at their home in Flint, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Barbie Rohde’s fingernail is decorated to represent Mission 22, the nonprofit she volunteers for that is focused on ending military and veteran suicide, on Friday, June 9, 2023, at her home in Flint, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

Their congressman heard, and called. He said he was sponsoring legislation to address veteran suicide — in community organizations outside of the VA — and asked if he could put their son’s name on it. Brenda Fox always loved hearing her son’s name. Then it was spoken on the floor of Congress. They’ve been contacted by organizations who received grant funding — from Alaska, Oklahoma, Wisconsin, Georgia.

The Foxes don’t consider themselves political people. But they call on the military and politicians to lead a cultural change in how the country talks about guns, consider reasonable restrictions, train soldiers how to get a gun away from a colleague in crisis.

“Everyone is always shouting: ‘You’re taking away my guns!’ Or, ‘We don’t need any guns!’” Brenda said. “There aren’t any easy solutions, and we know that. But thoughts and prayers aren’t cutting it.”

Earlier this month, the Army published its first major suicide prevention doctrine, after years of delays. It was criticized for including no clear guidance for how service members should act when someone in their ranks is suffering.

They are hard conversations to have.

Years ago, Jay Zimmerman, a peer specialist with the VA, talked with a struggling friend he’d served with. Zimmerman did the things the VA had trained him to; talk about mental health treatment, use sensitive language.

“But I never once thought to say, ‘Hey, what are you doing with your firearm? Where’s your pistol right now?’” he said. “And I got the call from his wife later that night that he had killed himself.”

He’s never not asked that question since then.

Zimmerman is from Appalachian Tennessee, not far from where Fox grew up. Guns are a part of life. Zimmerman used to sleep with two pistols under his pillow. He now encourages the veterans he’s counseling to calculate safety and risk in a different way: Sometimes, the immediate threat is an internal one, and having a gun in the bedside table doesn’t make you safer; it puts you in danger.

David Fox has spent weeks pining over this problem. He posted on Facebook: Please, if you ever have a suicidal thought, give your gun to a friend. You might think you’re OK right now, but that can turn in an instant, like a night of drinking, a car accident.

When he was going through his son’s possessions, it was the little things that hurt him the most: flashlights, weedeaters, evidence of building a life.

And there was the gun he’d used to end his. They hated this gun: they didn’t want to keep it, they also didn’t want it to circulate in the world.

David got a sledgehammer and took it out into the yard.

He smashed it into 20 pieces.

Barbie Rohde is reflected in a photo of her son, Army Sgt. Cody Bowman, at a festival while volunteering for Mission 22, a nonprofit that is focused on ending military and veteran suicide, Saturday, June 10, 2023, in Jacksonville, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

A young woman walked into Barbie Rohde’s booth, and said she felt she was running out of options.

“I’m scared every day, all the time,” she said.

The woman’s husband is a Marine who lost seven people when his battalion went to war. He doesn’t feel worthy of making it home.

He has dozens of guns, she said. Sometimes he sat on the tailgate of his truck, holding one and drinking. More than once, when he’d drink so much he passed out, she called his mom and said: “We have to get these guns out of the house.” They gathered them up and locked them in a trailer, and his mother took the key. He got mad at her the first couple times. But then he understood.

He started going to 12-step recovery for alcohol, and they assigned him a sponsor, a person who’s experienced his struggle, available all hours of the day. Why, he asked his wife, doesn’t the military offer him this, too, since they know soldiers trust their battle buddies?

The stress has worn on her, his wife said. She spent a week in a mental health facility.

“It’s hell, it really is,” she said.

She took one of Rohde’s business card with her cell number listed on it, and she answers every call, any hour of the day.

Rohde discovered the nonprofit Mission 22 shortly after her son’s death and now she does almost nothing else. She and her husband, Robert, have put 200,000 miles on their car. They set up at festivals all over Texas to sell T-shirts and caps and keychains to raise money for the charity that offers programs for struggling veterans.

But really, Rohde feels like she’s there to be a safety net for anyone who wanders into her path. They’ve gone so far as to drive five hours to pick up a veteran and take him to rehab. They often hear from wives and mothers who feel helpless, just like Rohde did.

She had asked for help, calling the base where her son was stationed to tell his commanders she was worried he might harm himself, and that he had guns, she said. She didn’t think her son would turn over the guns if she asked, but he was a “soldier’s soldier,” and she believes he would have given them to a fellow officer.

Instead, they told him she’d called, and he was furious at her.

He shot himself in his truck on Fort Sam Houston Army base in San Antonio.

“I have a lot of regret, I have a lot of anger over that,” she said. “There needs to be a network, a support system, to say ‘you’re going through some stuff, let me hang on to your guns.’”

Robert and Barbie Rohde talk with a veteran at a festival while volunteering for Mission 22, a nonprofit that is focused on ending military and veteran suicide, Saturday, June 10, 2023, in Jacksonville, Texas. (AP Photo/David Goldman)

She watched people walk by her tent and never even glance over. Sometimes she wants to grab and shake them, demand that they be angry about this, to tell them that next, it might be their kid.

“Everyone thinks it couldn’t happen to them until it does. I was one of those people,” she said.

The nonprofit they volunteer for recently changed its logo. It used to say “United in the War Against Veteran Suicide.” Now it’s “Veterans Family Community.” Rohde hates it.

“They need to say the word: suicide,” she said. “That’s the hard truth that needs to be out there.”

She has tattoos of the nonprofit’s logo all over her body, and when people ask her about them, she doesn’t hesitate to tell them how her son died, and how he should not have.

She obsessively tracks how much money she raises for the cause. She was disappointed at this festival; they raised less than $1,000 and her goal was twice that. She slumped her shoulders as they packed the unsold T-shirts and hats into their SUV.

Her husband thinks that deep down, it’s not really about the money for her — that’s just the easiest way to track how much people care, so when she goes to visit Cody soon at the national cemetery, she can whisper to him that his death was not for nothing.

She raised him as a single mom, and married her husband when Cody was a teenager. It was a hard life, they didn’t have much money, and her son was always smart and strong, with a big smile. He was analytical, he liked to take things apart and figure out how to put them together again. He followed the rules: he refused to go to a concert once because he heard people would be smoking weed.

He’d declared at 4 years old he would be “an Army guy” and never changed his mind. People ask her now, if she could turn back time, would she try to stop him. She says no. It’s what he’d always wanted.

She keeps an unwashed shirt he wore in a plastic bag in her dresser drawer. She tries not to take it out too often because she doesn’t want it to lose the smell of him. But when she’s having an especially bad day, she’ll hold it.

Other than that, a plot at a national cemetery is what she has left.

Her husband drives her there, spends a moment with her, then leaves her alone for however long she needs. Sometimes she stays for hours, sometimes she can’t bear more than a few minutes.

The morning after the festival, she fell to her knees in front of his marker. It’s etched with a number, 96-314. It’s always been easy for her to remember numbers — she can recall her childhood address, friends’ phone numbers. But she cannot bring herself to memorize this one.

She pulled weeds around his grave. She told him about the work she’d done for him, that she’s proud of him.

“I hope you’re proud of me,” she said. “We’re working really hard to prevent anyone from going to heaven the way you did.”

She hugged his marker; she said she was sorry, and kissed the cold stone.

The Associated Press receives support from several private foundations to enhance its explanatory coverage of elections and democracy. See more about the AP’s democracy initiative here. The AP is responsible for all content.

Text from AP news story, Veterans are more likely than most to kill themselves with guns. Families want to keep them safe, by Claire Galofaro.