A slow motion burial awaits in volcano no-go zone

A child’s swing. A fountain in a courtyard. A tray of glasses abandoned under the duress of escape. All will disappear as a blizzard of dark ash blows from a volcano on La Palma island and drifts to the ground inch by inch, foot by foot.

Inside the exclusion zone, there is destruction by lava as well as burial in a sepulcher of black snow. A living room furnished with a hammock sits empty in the final hours before an implacable tongue of molten rock crushes an entire house.

Whether the end comes from lava or from ash, homes and fields located below the Cumbre Vieja volcano face annihilation in slow motion.

Lava from a volcano advances next to a house as it continues to erupt on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Sunday, Oct. 31, 2021. The house was engulfed by lava from the volcano a few hours later this photo was taken. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Since the eruption started on Sept. 19, authorities have declared over 20,000 acres (8,200 hectares) between the Cumbre Vieja volcano and the Atlantic Ocean off-limits. Only police, soldiers, and scientists are allowed to move freely in the exclusion zone, which cuts La Palma’s western shore in two.

The lush land previously approximated an earthly paradise for both residents and visitors. Spaniards and other Europeans spent vacations or retired here to be near the sea, while locals harvested banana trees in the semi-tropical warmth of Spain’s Canary Islands.

Now, evacuated residents line up in cars and trucks on the zone's edge, awaiting permission to make escorted trips home to rescue their dearest possessions, or at least see their endangered properties.

Human time and geological time were brought into sync by the volcano. What once seemed a given - the land beneath people's feet - becomes as fluid and unpredictable as the lives the eruption threw into tumult. The creep of the lava, the build-up of ash, are matched by the growing anguish of the men and women whose way of life is being erased.

Silence would reign in the exclusion zone if it weren’t for what residents have named “the beast.” The volcano’s constant roar makes conversation almost impossible, nearly drowns out both the barking of abandoned dogs and the murmur of a flock of passenger pigeons circling the sky in search of a coop that no longer exists.

Another sound: families weeping as they are accompanied by police to witness their homes as they succumb. Lava flows have destroyed more than a thousand houses in their paths.

Scientists estimate the volcano also has ejected over 10,000 million cubic meters of ash. The ash is jettisoned thousands of meters into the sky, but the heaviest, thickest particles eventually give way to gravity. They accumulate into banks that slowly cover doors, pour into windows, make rooftops sag. Some particles are so big that when they pummel a car roof or the fronds of a banana tree, it sounds like hail.

Entire houses, right up the chimney, whole forests, right up to the canopy...the ash erases the distinguishing features of the landscape.

“I can’t even recognize my home,” Cristina Vera said while weeping. “I can’t recognize anything around it. I don’t recognize my neighbors’ homes, not even the mountain. It has all changed so much that I don’t know where I am.”

The quick relocation of over 7,000 people has prevented the loss of human life. At cemeteries, though, the occupants go through a second burial by ash, a burial that will wipe away the markers that note the place where they were put to rest.

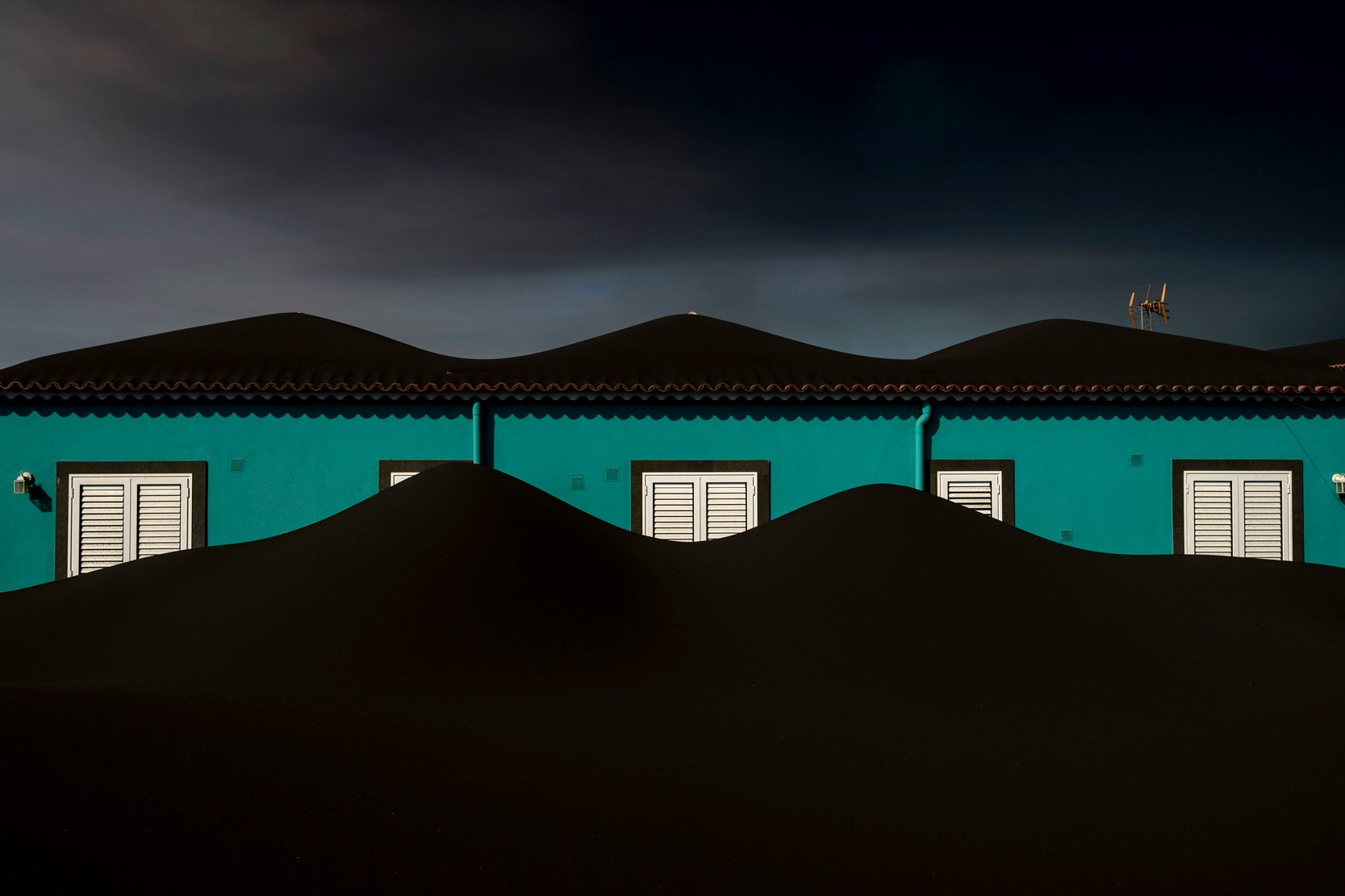

Yet amid the apocalypse, there are moments for the sublime to emerge. The colors that remain gain in their brilliance against the new ebony backdrop.

A scrub brush, shaken clean, becomes a luminous green globe, a sponge pulled from a coral reef, an orb from an alien world.

A hedge emerges from the ash spewed out by the volcano as it continues to erupt on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Monday, Nov. 1, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Ash from a volcano covers a crockery set let behind by resident who were evacuated from the village after the eruption of a volcano in La Bombilla on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Friday, Oct. 29, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Ash from a volcano covers the entrance of a house as it continues to erupt on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Thursday, Oct. 28, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

A fount is covered with ash spewed out by the volcano as it continues to erupt on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Monday, Nov. 1, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Jesus Perez holds a broom as he cleans the ash from a volcano at the roof of his house as it continues to erupt on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Thursday, Oct. 28, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Ash covers the ground near a volcano erupting on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Friday, Oct. 29, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

A cat sits next to boat covered with ash from a volcano in Puerto Nau on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Thursday, Oct. 28, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Ash from a volcano covers a sofa after the eruption of a volcano in La Bombilla on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Friday, Oct. 29, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Ash covers graves at the La Palma cemetery as volcano continues to erupt on this Canary island, Spain, Friday, Oct. 29, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Ash covers chairs at the terrace of a house as volcano continues to erupt on this Canary island, Spain, Saturday, Oct. 30, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Lava advances as volcano continues to erupt on this Canary island, Spain, Friday, Oct. 29, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

A swing is covered by volcano ash as it continues to erupt on this Canary island, Spain, Thursday, Oct. 28, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

A house is covered by ash from a volcano as it continues to erupt on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Saturday, Oct. 30, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Lava by the volcano advances destroying houses as it continues to erupt on the Canary island of La Palma, Spain, Monday, Nov. 1, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Ash cover the graves at the La Palma cemetery as volcano continues to erupt on this Canary island, Spain, Friday, Oct. 29, 2021. (AP Photo/Emilio Morenatti)

Text from AP News story, AP PHOTOS: A slow motion burial awaits in volcano no-go zone, by Emilio Morenatti and Joseph Wilson.

Photos by Emilio Morenatti

Visual artist and Journalist