Virus Outbreak Peru: The Vulnerable

Pushing a shopping cart with two children, César Alegre emerges from the large, deteriorated house near Peru’s presidential palace that is shared by 45 families to search for food. Sometimes he begs in markets. Sometimes he sells candies.

It is a task that was hard at the best of times, but with a month-long quarantine that has forced 32 million Peruvians to stay home and closed restaurants and food kitchens, it has become much harder.

In this March 29, 2020 photo, 72-year-old Maria Isabel Aguinaga, wearing a protective face mask, descends the stairs of her crumbling residential building nicknamed “Luriganchito” after the country’s most populous prison, in Lima, Peru. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

In this April 5, 2020 photo, Grace Lopez and Iunzu Asca do their homework sitting on a stoop inside the deteriorating building where they live, nicknamed “Luriganchito” after the country’s most populous prison, in Lima, Peru. (AP Photo/Rodrigo Abd)

The government has steadily tightened bans and lock-downs to slow the spread of the virus. This past week it ordered that only men can leave the house on Mondays, Wednesdays and Fridays, while only women can go out on Tuesdays, Thursdays and Saturdays. The trips can only be to the market, pharmacy or bank.

To try to address the humanitarian disaster, Peru has begun distributing about $400 million to feed 12 million poor people for one month.

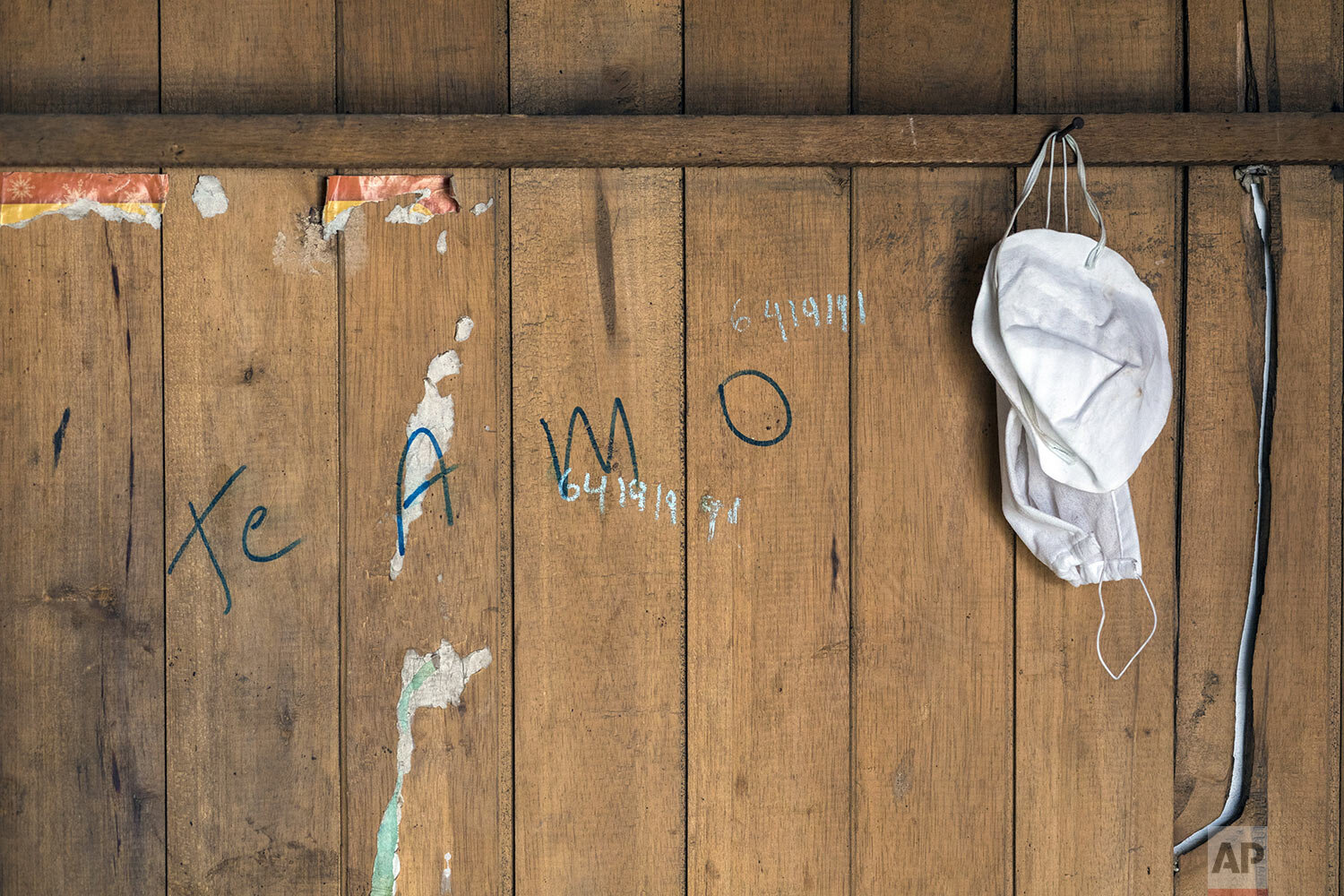

But the money doesn’t seem to be reaching most of the families in Alegre’s sprawling shared house. The building in Lima’s Rimac district is a relic from the area’s historic era and still has balconies from its better days. But inside its now-cracked walls is a warren of narrow, dark passageways that smell of damp clothing and marijuana.

Its residents have stories of hard luck and tough living.

Santos Escobar, a 68-year-old former mug seller, ended up living in “Luriganchito” after his house burned down twice. In the first fire, two of his six daughters died. In the second, both his legs were burned.

Nélida Rojas, 59, had a stroke two years ago that partially paralyzed her. She now uses crutches and begs for alms.

Nilú Asca is a 24-year-old single mother with two daughters. The youngest is 2 and has some type of hip dislocation or problem that forces her to wear a plaster cast.

Eating with his children in their small room, Alegre watches the news on an old television set. He believes what is preventing looting is the deployment of 140,000 uniformed officers to guard food markets and banks.

But his long-term outlook is not optimistic.

“The virus has highlighted the selfishness that man carries inside,” said Alegre.

Text from AP news story, Desperate hunt for food by Peru’s poor amid virus quarantine, by Franklin Briceno.

Photos by Rodrigo Abd