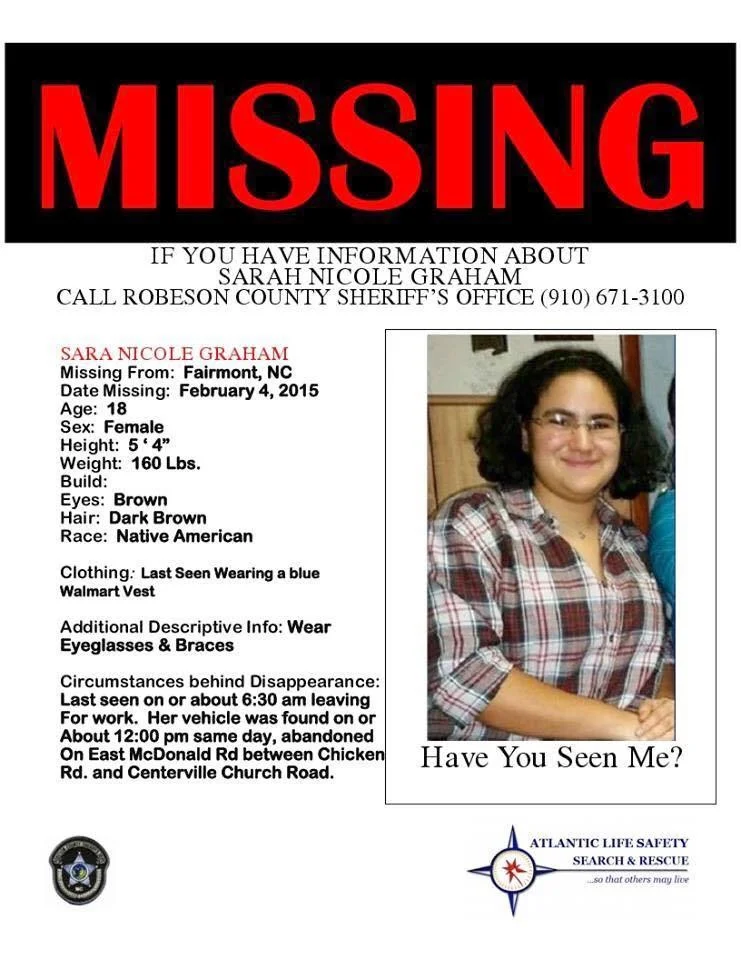

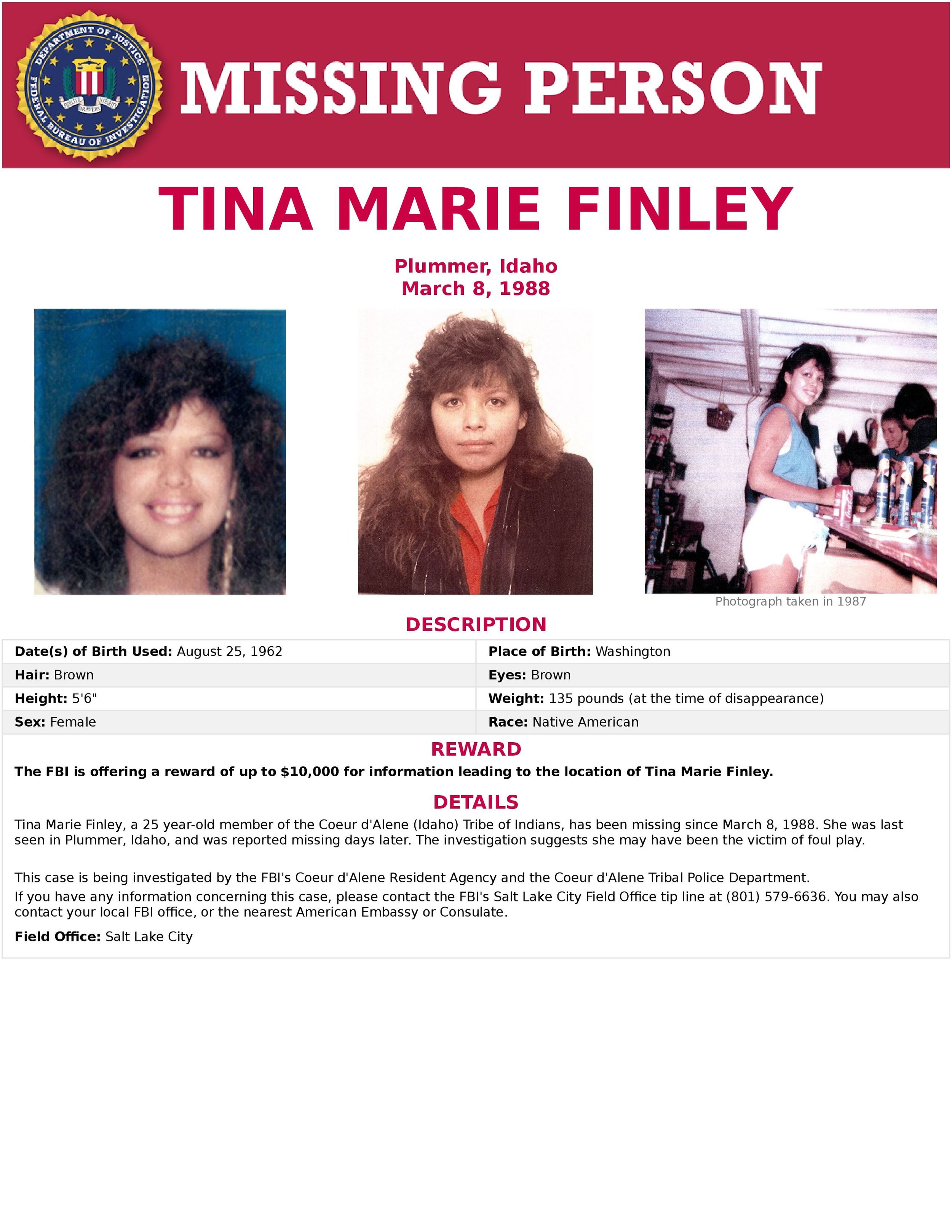

Haunting stories behind missing posters of Native women and girls

Their faces stare out from the posters, some happy, others inquisitive. Vital statistics and circumstances are summed up in a few sentences.

They are among an unknown number of missing and murdered Native American women and girls in the U.S.

Some have been gone just months; others vanished long ago. But each has loved ones waiting and wondering what happened to them, hopeful that raising awareness - and in some cases offering a reward - will solve the mystery and bring some kind of resolution, even if not the one they pray for.

Here are some of their stories:

Leona LeClair Kinsey, 45

Leona LeClair Kinsey was a fiercely independent woman who could go pheasant hunting, serve the bird for dinner, then take the leftover feathers and turn them into an artistic gift.

Her daughter, Carolyn DeFord, remembers how they'd also hunt deer, elk and antelope and pick mushrooms and huckleberries near their home in La Grande, Oregon, a rural community in the eastern corner of the state. "She was confident in her ability to not need people to do simple things for her," DeFord says, recalling how her mother would chop firewood and change her own tires.

Kinsey was 45 when she disappeared from La Grande in October 1999. DeFord believes her mother was likely a victim of foul play at the hands of a man she was supposed to meet who reportedly was a drug dealer. His whereabouts are unknown all these years later. Kinsey had struggled with alcohol and drugs.

A member of the Puyallup Tribe, Kinsey worked as a landscaper, a janitor and a motel housekeeper. She had a quirky sense of humor but also "a very dark and real concept of life," her daughter recalls. "She knew there were bad men," and when her mother was in her early 20s, she had a physically abusive relationship.

DeFord was 25 when her mother disappeared, and for nearly a decade, whenever she met someone new, she'd bring her mom up within minutes. "It was like I wore a nametag, 'Hi, my name is Carolyn. My mom is missing.'"

About 10 years ago, DeFord held a memorial for her mother, telling other mourners that "not a day goes by that I don't miss her." In recent years, she has become an activist in the missing and murdered Native American women movement, establishing a Facebook page featuring dozens of cases and reaching out to families to say: "'I'm so sorry that you're on this journey. ... I know the chaos that you're in right now. If there's anything I can do to help, let me know.'"

She is still healing herself, but sharing her mother's story, DeFord says, has given her purpose and a chance to raise awareness.

"It's a way to be a voice for women who haven't found theirs yet."

Click to enlarge

Lakota Rae Renville, 22

Lakota Rae Renville was so shy as a teen that when she graduated high school she was reluctant to walk across the stage.

She was a straight-laced girl who didn't smoke cigarettes, drink or take drugs, says her sister, Waynette. But her life took a dramatic turn after she met a man online in 2003 and moved from South Dakota to the Kansas City area.

Lakota, a member of the Sisseton Wahpeton Oyate Tribe, told her sister that she had a boyfriend who had two jobs, so she didn't need to work. She kept secret most everything else about her life.

Two years later, just 22 years old, Lakota was murdered. Her badly bruised, naked body was wrapped in a carpet pad, rolled in a blanket and dumped in a gravel lot in Independence, Missouri. No one has been arrested.

Police say Lakota was a prostitute who worked in Kansas City, but Waynette believes her sister was a victim of sex trafficking — a growing concern among law enforcement and activists in Indian Country. "She had to be forced into that line of work," she says. "She would never, ever do that."

For five years, Waynette called the police every week, hoping a new tip or DNA would lead to Lakota's killer. She did not want her sister forgotten. "She was loved," Waynette says. "She had lots of friends and family."

In January 2017, she says, her sister's boyfriend contacted her and denied having anything to do with Lakota's death. Waynette has little hope now that the case will ever be solved.

Lakota was buried on the South Dakota reservation. Her headstone is engraved with an angel.

"We're just not the same anymore," Waynette says. "It's agonizing to not know who did that, why they did that."

At first, Waynette says she was angry with the world because of Lakota's murder. Now, she says, breaking into tears, she feels differently, believing that whoever killed her sister "will deal with this — either in this lifetime or the next."

Click to enlarge

Rita Papakee, 41

Rita Papakee told her mother she loved her, then turned and walked into an Iowa casino. That was in January 2015. She hasn't been seen since.

Iris Roberts says her daughter, then 41, struggled with a drinking problem but would always call her when she went off with friends. But after she dropped her daughter off at the Meskwaki Bingo Casino in Tama, Iowa, there was nothing. Searchers scoured a wooded area and nearby towns. A private investigator was hired by the family.

Last May 5, the National Day of Awareness for Missing and Murdered Native Women and Girls, the Meskwaki Tribe helped organize a "Bring Her Home" walk to raise money for a continued search.

"I think about her every day," her mother says. "I pray every night and I pray every morning that she's going to be found, wherever she's at. I know I have to take care of her kids. That's what keeps me going."

Papakee was a mother of four; her two sons and two daughters range from 11 to 25. She loved to bake — snickerdoodle cake was her specialty — and go all-out celebrating the holidays with her kids, searching for pumpkins at Halloween, planning New Year's parties for them. Since her disappearance, her oldest daughter has given birth to a son.

Roberts says her daughter had been in and out of treatment for her alcohol use and later got involved with a man who was using methamphetamines. She's heard all kinds of rumors, including the possibility she was a victim of sex trafficking. But she has no answers, despite a $25,000 reward for information.

"It's terrible," Roberts says, "trying to live each day going on, but not knowing where she is and what happened to her."

Click to enlarge

Tanya Begay, 36

The last time Tanya Begay spoke to her mother she had called early one morning in March 2017, saying she planned to travel from the tiny Arizona town of Leupp back to her family's home near Gallup, New Mexico — a drive that should've taken just a few hours, from one part of the vast Navajo Nation to another.

A day earlier, Begay had made a stop near Tohatchi, New Mexico, to visit a relative's home with her boyfriend, marking the last time any of her relatives had seen her, according to a police report. Her mother reported her disappearance to officers in at least three different towns, including Gallup, where Begay had an apartment.

"At first, we were just like, 'OK, well she probably just went to Phoenix or somewhere like that,'" says Eliza Toddy, a longtime friend of Begay's. "'She'll be back.'"

But a police report says Begay's mother believed she might be in danger.

The 37-year-old Navajo woman, whom Toddy described as "bubbly," has two children. She had been close to her parents, and liked to text or call family and friends frequently before she vanished, Toddy said.

Click to enlarge

Freda Knowshisgun, 34

Freda Knowshisgun's family on Montana's Crow Indian Reservation began to worry something truly terrible may have happened when an aunt passed away in the fall of 2016 and she didn't come home.

Knowshisgun, a mother of three, always had been known to be especially gifted and bright in her large, tightknit family, says her older sister, Frances. But for about a year before she vanished, she had started to come and go from her family's home, sometimes disappearing for days at a time, as she fell on tough times and hung around with "the wrong people," her sister says.

In November 2016, her mother reported her missing to police, but officers initially told the family there might be little they could do since Freda was an adult and there was no known crime, according to her sister.

"It seemed like they weren't helping at all because she jumped into the wrong crowd," Frances Knowshisgun says.

The FBI has since become involved in the search for Freda, but every day that she's gone, the anguish over where she might be and what may have happened to her weighs on her family.

"It sits on our chest and shoulders," her sister says.

Click to enlarge

No one knows precisely how many missing and murdered Native American women and girls there are in the U.S., partly because some cases go unreported and others haven’t been accurately documented.

These posters represent women whose disappearances were reported, but whose cases remain unsolved. Click on a poster to enlarge it.

Text from the AP news story, Haunting stories behind missing posters of Native women, by Sharon Cohen and Mary Hudetz.

Visual artist and Journalist