Portrait of despair: Opioids land more women behind bars

This lone county jail in a remote corner of Appalachia offers an agonizing glimpse into how the tidal wave of opioids and methamphetamines has ravaged America. Here and in countless other places, addiction is driving skyrocketing rates of incarcerated women, tearing apart families while squeezing communities that lack money, treatment programs and permanent solutions to close the revolving door.

More than a decade ago, there were rarely more than 10 women in the Campbell County Jail in northeast Tennessee. Now the population is routinely around 60.

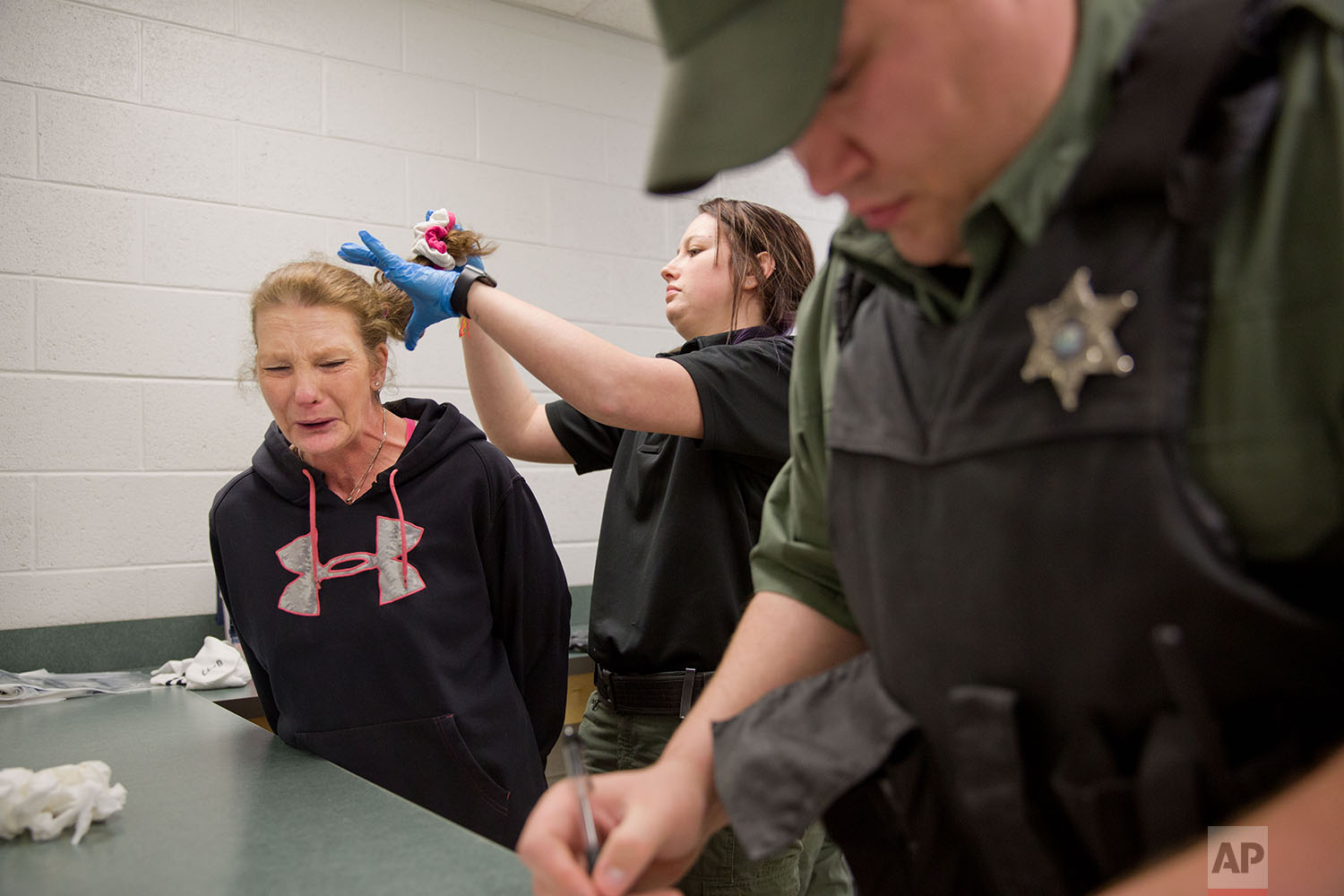

Most who end up here have followed a similar path: They’re arrested on a drug-related charge and confined to a cell 23 hours a day. Many of their bunkmates also are addicts. They receive no counseling. Then weeks, months or years later, they’re released into the same community where friends _ and in some cases, family _ are using drugs. Soon they are again, too.

And the cycle begins anew: Another arrest, another booking photo, another pink uniform and off to a cell to simmer in regret and despair.

Pills, though, aren’t the only problem. With 500 square miles of mountains, thick woods, winding back roads and deep hollows, this county on the Kentucky border has been a prime spot, too, for meth. While homegrown labs are on the wane, a powerful strain of the drug from Mexico has found its way here.

“Throw a rock, hit a house, and there’s drugs,” says Sarai Keelean, the 35-year-old inmate who says she didn’t have a major problem until she moved back about five years ago.

Krystle Sweat’s drug problems have consumed almost half her life.

Her parents still struggle to understand how the girl who sang in the church choir, played guitar and piano, and dabbled in gymnastics and cheerleading ended up this way. Her troubles began when she started hanging out with the wrong crowd and dropped out of high school.

The Sweats have raised Krystle’s son since he was about 3. Over the years, they’ve paid her rent, bought her cars, and invited her and her boyfriend to share their home. Sweat wound up stealing tools, a computer and camera _ anything she could pawn.

Blanche Ball, who has used, cooked or sold meth for 15 of her 30 years, has been in jail several times, mostly for short periods until now. She thinks about her four children constantly and recently dreamed her 3-year-old son was a doll broken into pieces.

“I know I could have done something more with my life,” she says, but: “Once you’re like this for so long, you don’t know another way to be.”

Text from the AP news story, Portrait of despair: Opioids land more women behind bars, by Sharon Cohen.

Photos by David Goldman