Slovak hospitals hold new Roma mothers against their will

Monika Krcova did not want to follow the official guidelines and remain in the hospital in Slovakia for four days after her third baby’s birth. And so she escaped.

Like many other Roma, she tells horror stories about giving birth in the hospital: How doctors at the Kezmarok hospital in eastern Slovakia slapped her face and legs repeatedly during the delivery of her first two children, screaming that she didn’t know how to push properly. How in the following days, she was subjected to racist taunts, and her postpartum pain was not treated.

Krcova knew that hospital staffers would stop her and her baby if she tried to leave after two days. So she waited until visiting hours, when the doors of the maternity ward were unlocked, and slipped away, alone.

Monika Krcova, center left, sits with her daughter Ivana and her grandchildren in their house on Nov. 14, 2018, in Podhorany village, near Kezmarok, Slovakia. Krcova is no longer afraid of her local hospital since she isn’t planning to have more children, but worries about her daughter Ivana, who says she also was slapped by nurses when she previously gave birth and is now pregnant. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

Slovakia’s Ministry of Health strongly recommends four-day stays for mothers and babies, regardless of their health. But many hospitals — seeking insurance reimbursements — have turned that guidance into a mandate.

An investigation by The Associated Press has found that women and their newborns in Slovakia are routinely, unjustifiably and illegally detained in hospitals across the European Union country. Women from the country’s Roma minority, vulnerable to racist abuse and physical violence, suffer particularly. They’re also often poor, and mothers who leave hospitals before doctors grant permission forfeit their right to a significant government childbirth allowance of several hundred euros.

When Krcova returned to pick up her infant a couple of days after she left, the hospital charged her 20 euros ($23) — an illegal fine.

“It felt like punishment,” she said. “If you and your baby are healthy and you have to stay there, it’s like prison.”

Homes are reflected off the window of Monika Krcova's house as her grandchildren play inside at the Podhorany village on Nov. 14, 2018, near Kezmarok, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

In October, the AP reported that hospitals in more than 30 countries illegally hold patients when they cannot pay their bills, including in Kenya, Congo, India, the Philippines and Bolivia. While there are some differences, some experts say the situation in Slovakia — which also is seen to some extent in other eastern European countries like Bulgaria and the Czech Republic — amounts to hospital imprisonment.

“Detention in African hospitals is about money, but in Slovakia, it’s about power,” said Zuzana Kriskova, a maternal rights activist. “Women are having their fundamental human rights violated when they have no freedom of movement and cannot decide how their child is to be treated.”

Dark clouds hover over Podhorany village after a storm on Nov. 14, 2018, near Kezmarok, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

People run during a dog fight in a village on Nov. 12, 2018, near Kezmarok, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

A Roma girl carries a bucket on Nov. 16, 2018, in a village near Kezmarok, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

In the U.S., the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists says women with no delivery problems can be discharged with their babies after one to two days. Britain recommends women and their infants stay for at least six hours after an uncomplicated birth, but they are free to leave at any time. International human rights law prohibits the forced detention of a woman or her baby after she has given birth, as long as there is no imminent danger to anyone.

Slovak doctors, however, say babies must be kept in the hospital because numerous screening tests are needed. The Ministry of Health said they are currently considering shortening the required period of post-birth hospitalization to three days, but that new mothers “should follow the instructions of the attending physician” on issues including when they and their newborns are allowed to go home.

An empty delivery room is pictured on Nov. 15, 2018, in the Trebisov hospital in Trebisov, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

A nurse walks past a room as Paulina Balazova swaddles her newborn baby at a hospital on Nov. 15, 2018, in Trebisov, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

“I know of no medical evidence to justify what’s being done to women and their newborns in Slovakia,” said Mindy Roseman, a global health and human rights expert at Yale Law School. “They’re basically being kidnapped and unlawfully detained.”

Hospitals and insurance play a central role. Several hospital staffers said institutions often only get reimbursed if mothers and babies stay for at least four days after delivery.

Dovera, Slovakia’s biggest private health insurance provider, said it reimburses hospitals separately for mothers and newborns and that the minimum length of stay after childbirth for both is four days. It said mothers can leave earlier if they have a signed application approved by the hospital.

The situation weighs most heavily on Roma (also known, pejoratively, as Gypsies). Having suffered from discrimination across Europe for generations, they say they are treated abysmally by hospitals.

Numerous Roma women who fled hospitals told the AP they were tied up and beaten, shouted at, or ignored when they needed medical attention, including during birth. Some said there were often two women and babies squeezed into a single bed; others said the health care staff laughed at them, saying they were dirty and had too many children. Many women declined to give their names, fearing retribution from local authorities.

“For Roma, they treat us worse than dogs,” said Krcova, who was only allowed to see her newborn babies two days after they were born. She is no longer afraid of her local hospital since she isn’t planning to have more children, but worries about her daughter Ivana, who she says was also slapped by nurses when she previously gave birth and is now pregnant again.

One Roma woman tearfully told the AP that when she escaped from Kezmarok hospital after giving birth to twins four years ago, she got sick and couldn’t retrieve them for 10 days. By that time, the institution had given away her baby boy and girl to an orphanage. She has not seen them since. She would not give her name, fearing the hospital would refuse to treat her family.

Maria Lumkova, a Roma health assistant, said there are usually about three such cases every year in the village where she works.

Alzbeta Siva, a spokeswoman for Kezmarok hospital, also known as the Dr. Vojtecha Alexandra Hospital, said Roma babies left in a hospital can be sent to an orphanage, but only “rarely.” She also acknowledged that nurses do strike Roma women during delivery.

“Sometimes there are cases like that, but very few,” she said.

A nurse dresses a baby at the Kezmarok hospital on Nov. 16. 2018, in Kezmarok, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

Three babies whose mothers absconded the hospital, rest in their cribs at the Kezmarok hospital on Nov. 16, 2018, in Kezmarok, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

At the Kezmarok hospital in mid-November, four out of 17 newborns were still being detained after their mothers absconded. Siva said Roma mothers fleeing the hospital after birth was “an everyday occurrence” and that mothers were charged 4 euros ($4.60) every day their baby was held in the mother’s absence.

Officials at several other hospitals in the region estimated that about 10 to 25 percent of Roma women slip out of the hospital within two days of giving birth, leaving their babies detained.

Some doctors said Roma women were taking advantage of the situation. Dr. Jozef Adam, head of gynecology and obstetrics at the J.A. Reiman University Hospital in Presov, said Roma women worry that their husbands will be unfaithful: “They run away to be with their men. They know their babies will be taken care of here so they leave them.”

In 2014, the Slovak government passed a law that penalizes women who leave the hospital after birth without permission, by withholding social benefits payments of up to 800 euros ($914). Critics say the law unfairly targets Roma women, who are disproportionately affected by the penalty, since they typically have few resources.

Even white, privileged Slovak women complain they have been imprisoned by hospitals after giving birth.

Renata Kupcova Kazimirova had her daughter Sona in early November, and was told they were both healthy. But when she informed the head of obstetrics that she wanted to leave with her baby the following day, a struggle ensued.

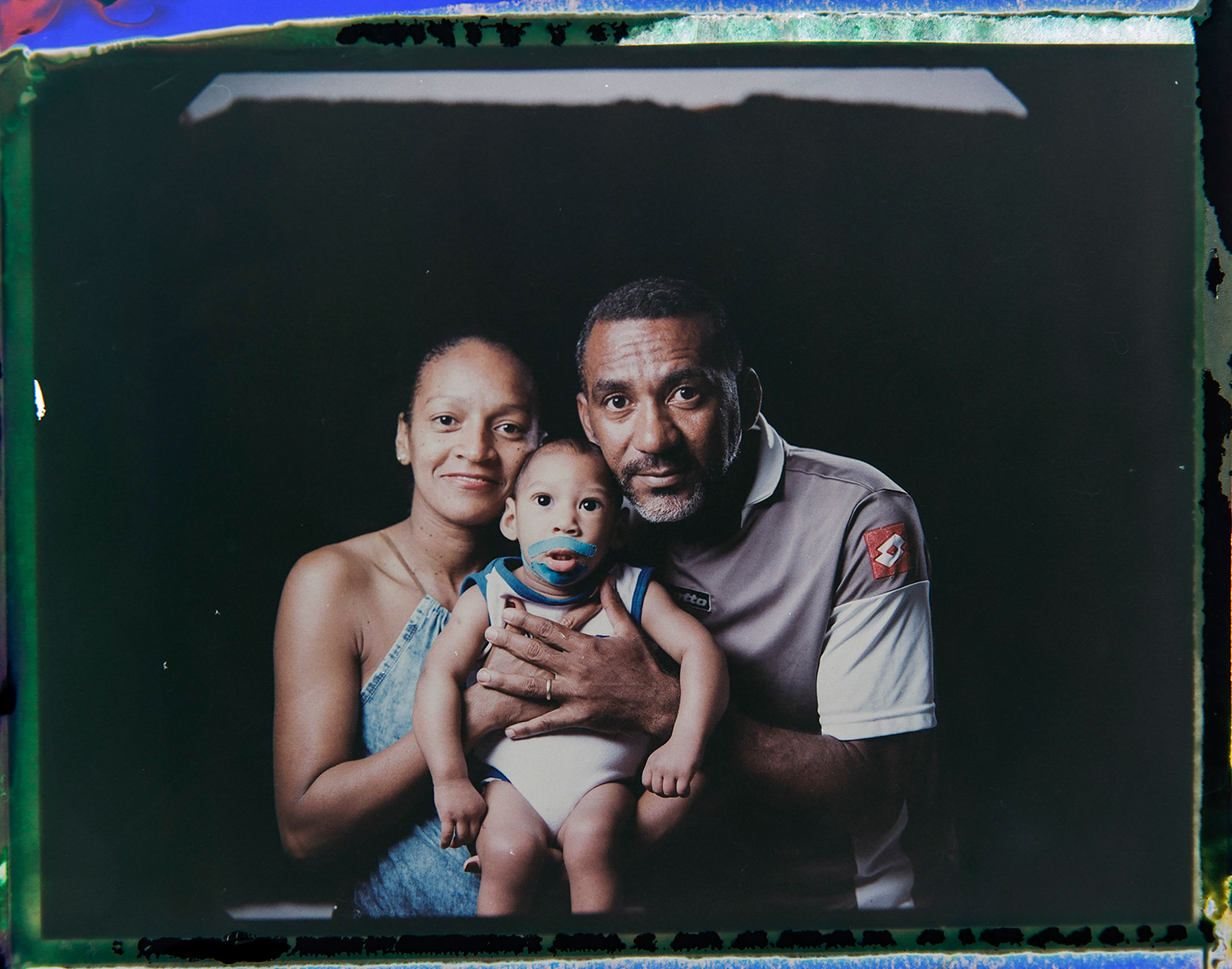

Renata Kupcova Kazimirova holds her daughter Sona next to her son Vladko, right, as she sits with her husband Vladimir on Nov. 11, 2018, in their home in Hlohovec, Slovakia. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

“They told me that a woman after birth does not have the capacity to make this decision,” Kazimirova said. “And they told my husband: ‘There is no way this baby is leaving.’” During the next three days, Kazimirova and her husband clashed repeatedly with doctors, who threatened to call the police and social services if the couple left with their newborn.

“I was crying constantly,” Kazimirova said. “I didn’t have the ability to protect my daughter and bring her home.”

Theoretically, women who want to leave the hospital before obtaining doctors’ approval are to be given a legal form to sign, acknowledging they are leaving the hospital against medical advice.

“If a woman keeps insisting that she wants to leave, that’s when the psychological terror starts,” said Zuzana Kostkova, a midwife at a Bratislava university hospital. “They will play on a mother’s fears, and say things like, ‘what if there’s a problem with the baby’s heart?’ and they will refuse to bring the (legal) form she has to sign.”

In practice, Kostkova said, it was impossible for any woman to leave the hospital before doctors agreed. To avoid Slovakia’s obligatory hospital detention period after birth, Kostkova simply had her baby across the border in Austria.

Most Roma women, however, lack the finances for such options.

Jarmila Noskova, 33, stands at the entrance of her house with her daughter on Nov. 14, 2018, in Podhorany village near Kezmarok, Slovakia. Noskova, a Roma woman now pregnant with her seventh child, said she cried for days every time she was forced to remain in the hospital after birth, terrified the hospital would alert the police if she left. (AP Photo/Felipe Dana)

Jarmila Noskova, a Roma woman now pregnant with her seventh child, said she cried for days every time she was forced to remain in the hospital after birth, terrified the hospital would alert the police if she left.

“I was told to stay in the hospital,” she said, “and so I endured it for my baby.”

Text from the AP news story, Slovak hospitals hold new Roma mothers against their will, by Maria Cheng.

Photos by Felipe Dana