Operation Dynamo: The Dunkirk Spirit

When Operation Dynamo ended on June 7, 1940, more than 300,000 Allied troops had been rescued from the harbor and beaches of Dunkirk, France from the encircling German war machine.

The vast majority of the British Expeditionary Force (BEF) that had battled alongside the French and Belgians in trying to stop the Nazi advance in Europe was saved and in being saved the course of World War II was surely altered.

The BEF lost most of its equipment and armor but the fighting force survived to battle again and in time, four years later, the Allies with the United States now in the war, once more crossed the English Channel in June 1944 on D-Day.

Soldiers of the British Expeditionary Force wade out to some of the little ships that are attempting to evacuate them from Dunkirk, France, on June 1, 1940. (AP Photo)

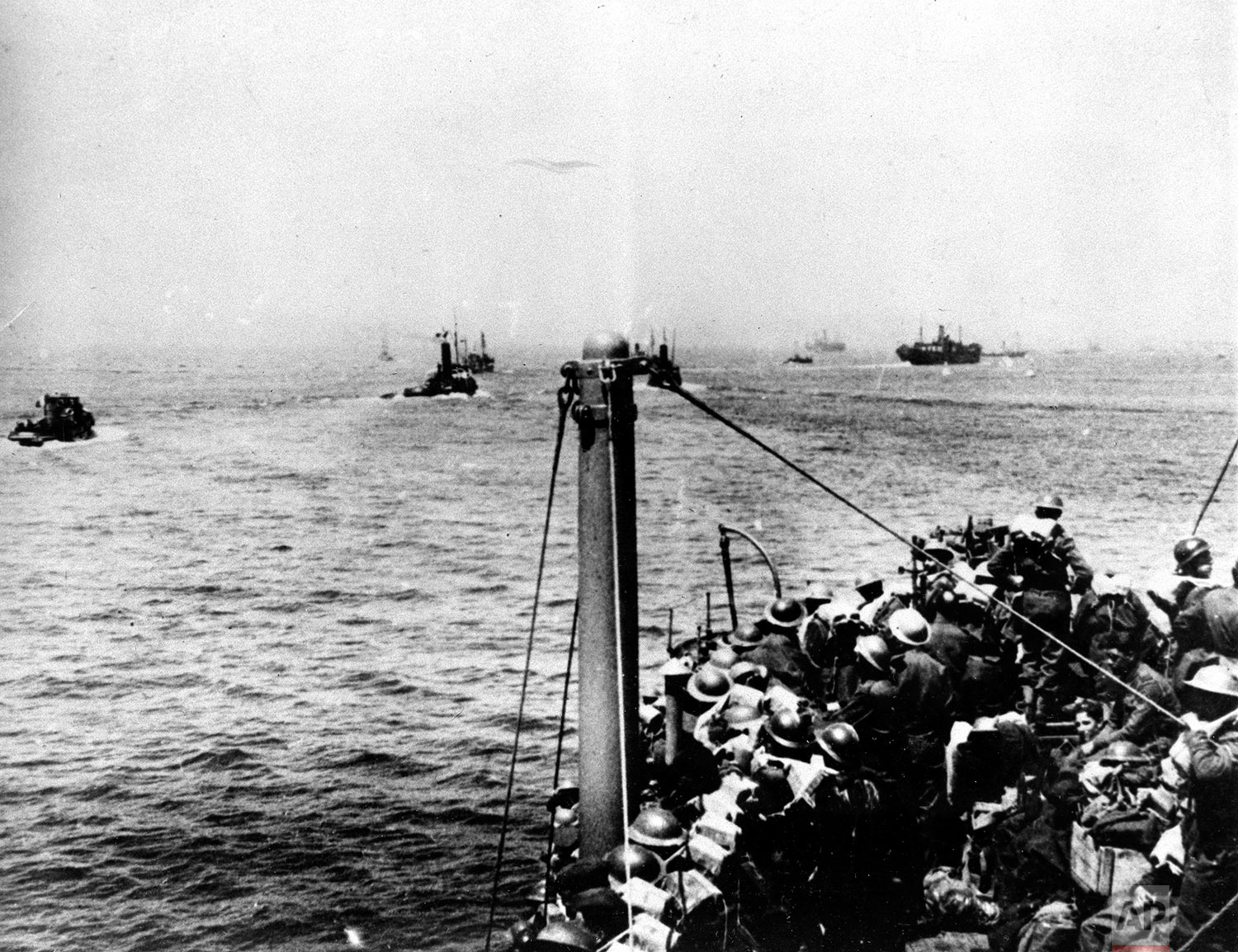

Hundreds of men of the British Expeditionary Force withdrawn from Dunkirk and Northern France are arriving back in England in a continuous stream. A destroyer’s deck loaded with men of the B.E.F., May 31, 1940, somewhere in England. (AP Photo)

The story of Dunkirk is told in Christopher Nolan’s new film of the same name. The Associated Press’ Lindsey Bahr writes in her review that “Dunkirk” is “a stunningly immersive survival film” and “a stone cold masterpiece.” She goes on to write “the screen and images envelope you with urgency, dread and moments of breathtaking beauty and grace as you wait with the soldiers, as the title card at the beginning says, for deliverance.”

Actors wait on the beach before filming a scene for the film, "Dunkirk," in Dunkirk, northern France, Thursday, May 26, 2016. The film, directed by Christopher Nolan, tells the story of the Dunkirk evacuation. (AP Photo/Michel Spingler)

Operation Dynamo, as the rescue operation was called, began on May 27, 1940, after a German pincer advance forced the BEF into retreat and cut off all ports except for Dunkirk. Under heavy shelling and air attack from the German Luftwaffe, the British soldiers, known as Tommies, as well as French and Belgian troops were evacuated. British destroyers sent to perform the rescue couldn’t get close enough to shore due to the shallow waters, so smaller vessels had to act as ferries to bring men off the beach.

A member of the German Wehrmacht looks through a pair of binoculars on French and British prisoners of war in the harbor of Dunkirk on the Western Front in France, June 1940. (AP Photo/DPA)

An AP story from 1940 reported on the operation:

A SOUTHEAST COAST PORT IN ENGLAND, June 1.—Britons claimed the biggest rescue in military history as it was estimated unofficially today that between 75 and 80 per cent of the British Expeditionary Force in Flanders had been extricated by the Allied navies from the death trap laid by the Nazis.

Since the original strength of the B. E. F. sent into Belgium at the beginning of the wide-open war in the west was placed at 175,000 men, this meant that from 130,000 to 140,000 Tommies had been brought to the safety of English shores by the mighty armada of war-ships, merchantmen, fishing boats, yachts, barges and other craft of every size and description.

Two of the many small boats which helped to bring the Allied troops in the emergency evacuation across the English Channel from Dunkirk, France, are shown on June 4, 1940 in World War II. (AP Photo)

"The Salvation Navy" fisherman, longshoreman, full-time and part-time seafaring folk and yachtsmen all did their bit in the transference of B.E.F. and French troops from Dunkirk to England. Many thrilling tales will eventually be told of "The Salvation Navy" shown June 24, 1940, with a scratch crew captained the cabin cruiser "Mimosa" from Shoreham Harbor to Dunkirk to assist in the work. He is seen coming ashore followed by Mr. Clark, who organized left Shoreham to assist in the work. (AP Photo)

In another report dated June 2, the crewman of a motor boat described the conditions:

“Explosions kept going on around us all the time,” the coxswain said. “The motor boat was nearly blown out of the water time and again. Every trip the small boats were loaded to the thwarts and soldiers baled water with their tin hats. Once we carried fifty Highlanders. We kept on until all troops in that and other parts of the beach had been removed.”

Troops of the British Expeditionary Force view the Nazi bombardment of Dunkirk from a transport after their evacuation from the French coast during World War II. (AP Photo)

Photographs from the AP Images archive show the scene of the evacuation often in blurry images of the beaches and with more clarity when depicting the rescued men aboard ship: Soldiers wade out into the surf to what became known collectively as the Little Ships; scores of smiling faces appear under the steel helmets of the Tommies as they arrive in England; men wait in long, curving queues on the beach of Dunkirk; black smoke billows from nearby burning oil tanks; the beach is dotted with greatcoats abandoned by departing troops; a fleet of ships large and small, seen in grainy black and white, make the journey back to the English coast.

Thousands of British and French troops massed on the beach of Channel port in Dunkirk, France on June 4, 1940 awaiting ships to return them to England. (AP Photo)

Called “the greatest rescue in military history” by the AP in 1940, the rescue at Dunkirk was pivotal in shaping the course of the war. Without the bravery of soldiers, sailors, airmen and civilians alike the evacuation would not have succeeded:

The coxswain said the first words they heard when they reached the Flanders coast was the exclamation of an infantry officer: “Thank God, there are such men as you!”

Now that’s the Dunkirk spirit.

Written content on this site is not created by the editorial department of AP, unless otherwise noted.

Visual artist and Journalist