36 years and five presidents: The work of J. Scott Applewhite

Before he picked up a camera, J. Scott Applewhite was first inclined to study biology during his early college years. And he points to a Darwinian idea to explain why he is in his fifth decade as a photojournalist: The species that survive are those best able to adapt to a changing environment.

“Perspective comes with some longevity and I clearly see now what has always been there: change,” says Scott, who started out shooting film developed in wet darkrooms and now shoots, edits and files digitally from any location.

“In essence, we are always in a state of transition. The business of news may have suffered, yet today more people get their information visually than ever before -- we are a big part of that.”

Scott was born in Texas and raised in small towns in Kentucky before moving to Louisville in his teens. A friend at Western Kentucky University was a photographer on the college paper, the College Heights Herald, and Scott found himself spending more and more time in the darkroom. Soon, he had a camera of his own and was shooting every day.

“We all skipped classes and worked long hours at the school newspaper,” he says. “I may have been taking college courses, but this is where I got my education.”

A highlight of Scott’s college years came with the devastating 1974 outbreak of tornadoes in Kentucky and a dozen other states. The Louisville Courier-Journal arranged for Scott to travel to a devastated area -- by helicopter. “I thought, ‘People do this for a living?’ I was hooked.”

“ In essence, we are always in a state of transition. The business of news may have suffered, yet today more people get their information visually than ever before — we are a big part of that.”

An extended internship with the Courier-Journal led to full-time jobs at the Henderson, Kentucky, Gleaner, The Palm Beach Post and The Miami Herald. He became the main Florida stringer for The Associated Press, learning the wire from Miami photo editor Phil Sandlin. When rioting broke out in May 1980 in the Liberty City section of Miami, Scott was a critical source of photos for the AP.

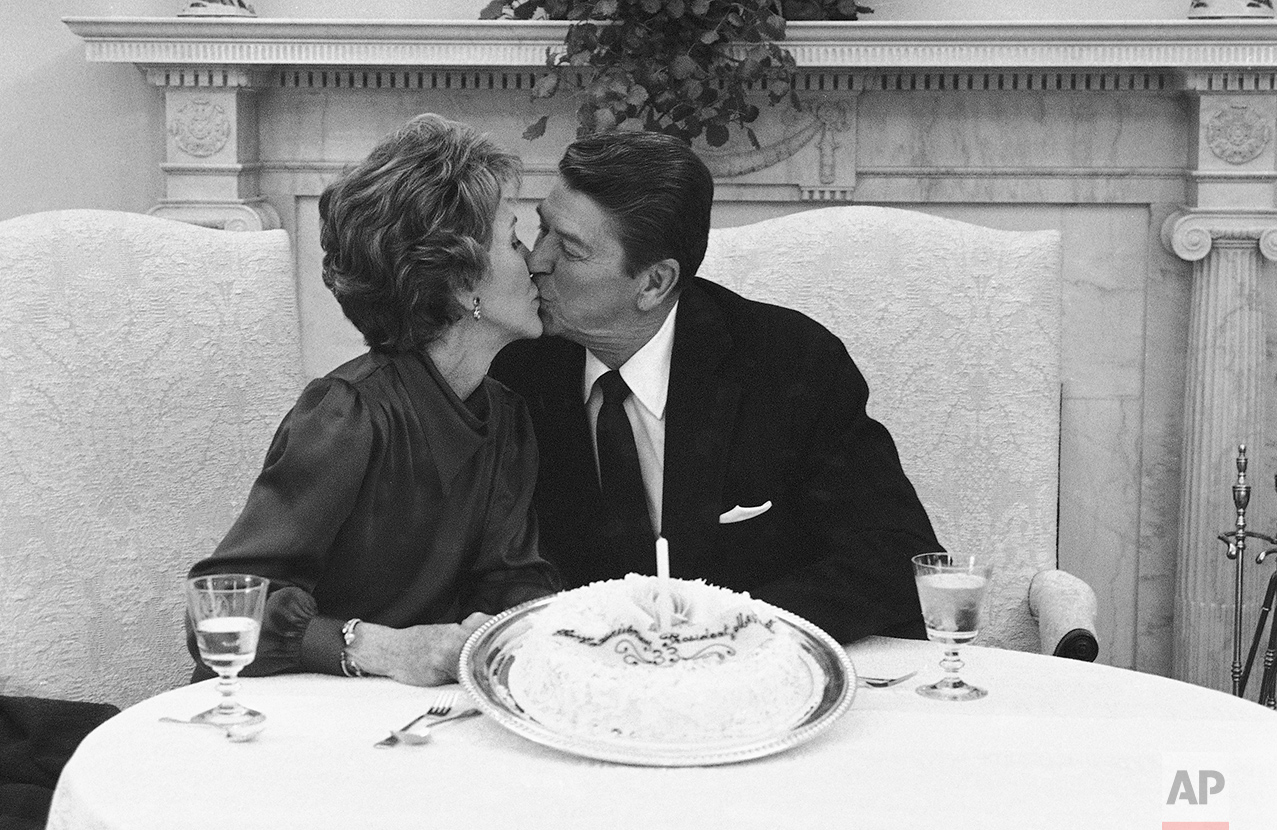

Among those taking notice was Hal Buell, AP’s photo chief, who hired Scott for the Washington bureau’s photo staff. In January 1981, Scott and Ronald Reagan went to work in the nation’s capital. Scott joined the White House and Capitol rotation and adjusted to the more regimented ways of covering government and politics in AP’s largest bureau.

“The AP was always pushing the envelope on coverage,” he says. “And it wasn’t just the cameras and the technology, it was the people I worked with who passed on their knowledge, experience, failures and triumphs. AP veterans Bob Daugherty and Charlie Tasnadi, and fellow staffers like Ron Edmonds were great teachers – about being prepared, being on time, being respectful, and being one-up on the competition.”

A turning point came when Scott discovered he had a gift for being an AP “fireman,” able to hit the ground in an unfamiliar hot spot, overcome the risks and deliver front-page news photos. An AP editor in New York remarked: “With Applewhite, we just say ‘go’ and the next day pictures start rolling in. Like a ‘fire and forget missile.’” He maintained a big bench in his garage suppliecd with essentials for any assignment: military invasions, disasters, the Mideast, and extended stories from conflict zones.

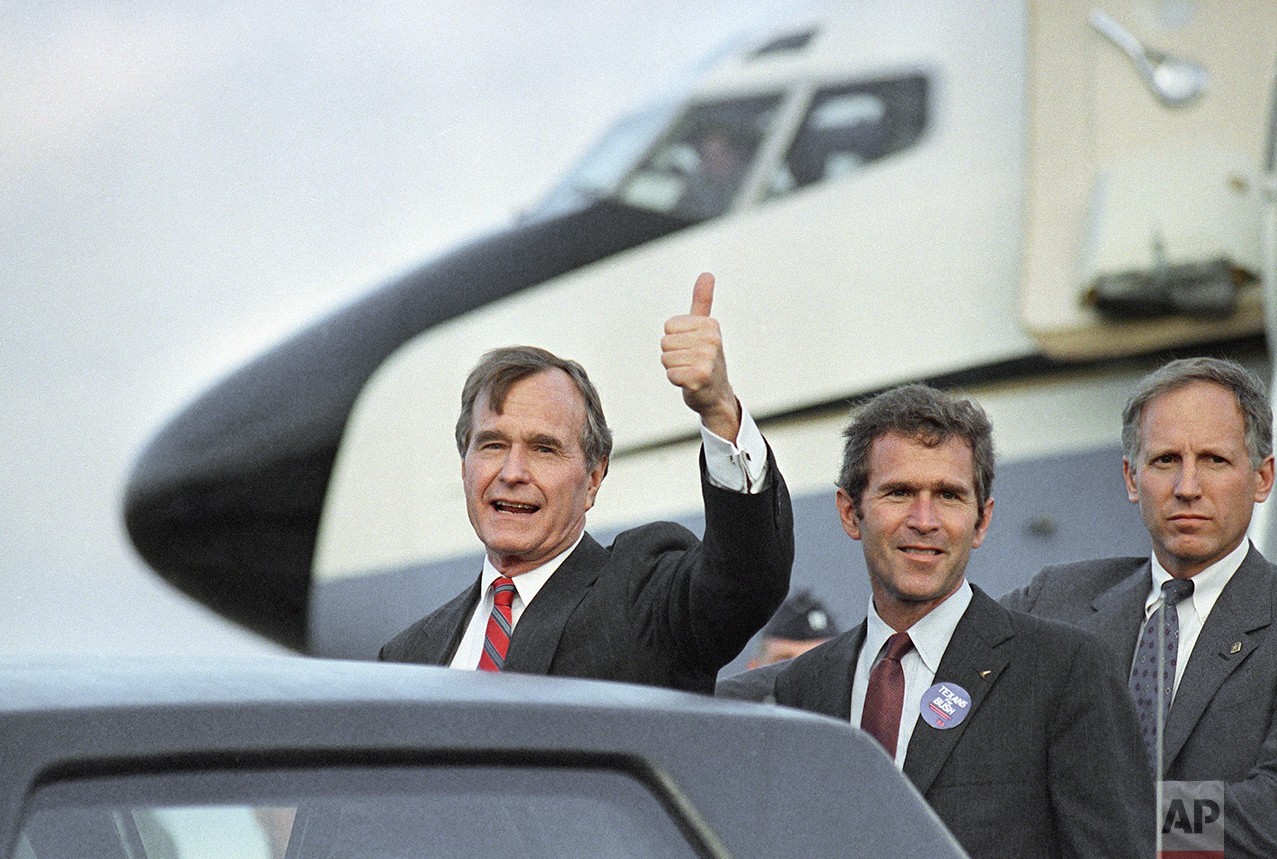

Haiti, Somalia, Iran, the Balkans, the first Gulf War -- Scott peeled off from the White House assignments as needed but still contributed to such events as Reagan’s visit to the Berlin Wall, presidential campaigns and the Monica Lewinsky scandal. In Haiti, he took pictures of deadly riots and even heard the buzz of a bullet flying past his head. Applewhite was a key member of the AP photo staff that won the Pulitzer Prize for Feature Photography in 1993 for the US. presidential campaign and again in 1999 for the Clinton impeachment.

By 2011, Scott was staying closer to home and developing a new expertise: covering a divided Congress and capturing images that reveal the drama of the Hill.

Today, 36 years and five presidents after moving to Washington, he offers his advice and expertise when the newest photojournalists face their own challenges in a digital age.

And Scott isn’t done yet, never mind the WHNPA’s lifetime achievement award.

“I feel more complete as a journalist than I ever have before. The tools are better -- the best cameras I’ve ever had -- and I’m a better news photographer than I’ve ever been. And this is the single best staff that we’ve had in the 36 years I’ve been here -- the most balanced, energetic, smartest, sophisticated photojournalism staff now.”

“I guess I don’t feel like I’ve peaked. I feel like I’m better understood, maybe better known, and certainly taking better pictures. I feel like a valuable part of the AP. For me,” he says, “the payoff is now.”

Below is a selection of Applewhite's work through the years.

Follow AP photographers on Twitter

Written content on this site is not created by the editorial department of AP, unless otherwise noted.

Visual artist and Journalist