San Diego’s sunny identity threatened by homeless crisis

Christine Wade found a haven in the tent she shared with six children, pitched in an asphalt parking lot.

It was, at least, far better than their previous home in the city, a shelter where rats ate through the family’s bags of clothes and chewed on 2-year-old Jaymason’s stroller. Roughly 50 of the encampment’s 200 residents were children, so Wade’s kids had plenty of playmates.

“It’s peaceful here,” Wade, 31, who is eight months pregnant, said in an October interview. “There’s coffee first thing in the morning. We can hang out here in the daytime. I mean what more could you ask for?”

A tent, of course, is not a home. But for these San Diegans, it is a blessing.

Like other major cities all along the West Coast, San Diego is struggling with a homeless crisis. In a place that bills itself as “America’s Finest City,” renowned for its sunny weather, surfing and fish tacos, spiraling real estate values have contributed to spiraling homelessness, leaving more than 3,200 people living on the streets or in their cars.

Most alarmingly, the explosive growth in the number of people living outdoors has contributed to a hepatitis A epidemic that has killed 20 people in the past year — the worst U.S. outbreak of its kind in 20 years. Deplorable sanitary conditions help spread the liver-damaging virus that lives in feces.

“Some of the most vulnerable are dying in the streets in one of the most desirable and livable regions in America,” a San Diego County grand jury wrote in its report in June — reiterating warnings it gave the city repeatedly over the past decade to better address homelessness.

San Diego has struggled to do that. Two years ago, Mayor Kevin Faulconer, a moderate Republican, closed a downtown tent shelter that operated for 29 years during winter months. He promised a “game changer” — a new, permanent facility with services to funnel people to housing.

But it wasn’t enough.

The result? Legions of Californians without shelter. A spreading contagion. Endless political disputes over what can and should be done — and mounting bills for taxpayers. Struggling schools and other institutions. And an extraordinary challenge to the city’s sunny identity that threatens its key tourism industry.

For now, San Diego again is turning to tents. The campground where the Wades lived was only temporary; this month, officials are opening three industrial-sized tents that will house a total of 700 people.

There are plans afoot to build less-makeshift housing. But to deal with the immediate emergency and operate the giant tents, the city had to take $6.5 million that had been budgeted for permanent homes.

Democrat Councilman David Alvarez cast the only vote against the plan. “Had we actually invested in a homeless strategy, we would not be here today being asked to warehouse 700 people in giant tents,” he said.

Republican Councilwoman Lorie Zapf’s mother was mentally ill and died homeless in Los Angeles. She agreed with Alvarez that the tents were not a perfect solution to San Diego’s crisis, but she could not in good conscience pass up a chance to get people off the streets.

“We need to do anything we can to stop this tsunami of people who are ending up on our sidewalks,” she said.

___

“The people of San Diego need to decide what they want the city to look like,” said Gordon Walker, who took the helm this summer of the San Diego Regional Task Force on the Homeless amid praise for his efforts in combatting chronic homelessness in Utah.

“San Francisco has essentially given up its streets to the homeless,” added Walker, who served as deputy undersecretary for the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development during the Reagan administration. “It could go either way here. The real issue is we don’t have enough housing.”

Last year, the number of people living outdoors in San Diego jumped 18 percent over the previous year, according to an annual count taken in January. More than 400 makeshift shelters sprung up downtown, covering sidewalks across from new high-rise apartment buildings that have climbed in lockstep with the booming biotech-heavy economy and soaring rents, among the nation’s highest. A studio apartment goes for around $1,500 a month, on average.

Most of the homeless, like the Wade family, did not migrate to San Diego to live on the streets but are local residents who became homeless in a city where rents increased nearly 8 percent in a year. High-rise buildings have replaced discount residential buildings that offered single rooms for rent, housing people living paycheck-to-paycheck. Nearly half of the 9,000 rooms have disappeared since 2003.

In October, as the hepatitis death toll climbed and the city declared a homeless emergency, Faulconer and the nonprofit Alpha Project opened the Balboa Park campground where the Wades found shelter. The city installed public washing stations, opened 24-hour restrooms and scrubbed streets with a bleach solution.

Police also cracked down, issuing hundreds of citations, largely for illegal lodging. Within weeks, the nearly 400 tents and tarps downtown were gone. Those who work with the homeless say they simply scattered.

“It could be like a campfire when all the embers are spread out. It either dies out or it catches other areas and makes a bigger fire than we originally had,” said Dr. Jeffrey Norris, the medical director of Father Joe’s Villages, which runs a clinic that treats 2,800 homeless annually.

The number of encampments hidden in the brush and bamboo along the banks of the San Diego River doubled.

“It’s being used as a toilet,” said Zapf, whose council district includes the river, bays and beaches.

The San Diego River Park Foundation’s mission is to preserve the river, a green ribbon that starts from snowmelt in the mountains east of San Diego and builds as it snakes through a valley of cottonwood groves and continues under freeway overpasses by shopping centers.

The foundation spent $115,000 removing 250,000 pounds of trash left by the homeless camps this year. Litter is carried by the river, which feeds into the Pacific at a popular dog beach.

Director Rob Hutsel said he gets asked by potential donors about the foundation’s plans to create a 52-mile-long river park and trail system: “What about the homeless? Don’t build a park. It’ll just bring in more.”

“Gosh, parks are good,” he said. “There shouldn’t be any thought about building a park. That’s so unfortunate.”

___

Laurie Britton operates an organic coffee roasting business and coffee shop, Cafe Virtuoso, in the Barrio Logan neighborhood. The winter shelter was nearby, and Britton was among those who supported its closure two years ago because it drew throngs of homeless people to the area.

But when it closed, the problem exploded. Tents, tarps, shopping carts, needles and trash spilled into the street, making it difficult to drive to her cafe.

Her customers’ cars would get bashed by bottles or sprayed with urine. People locked themselves in the bathroom to do drugs. One Saturday, Britton dressed up to give a tour but had to scrape piles of human feces off the sidewalk first. Another morning, a man flashed a knife and glared when she asked him not to put a tarp next to her cafe’s parking fence.

She issued pepper spray to her 14 employees.

“If it gets out of hand, the girls know to grab the pepper spray and do what you have to do,” she said. “The reality is I am here to protect my customers and employees. It’s not my job to give you a bathroom and free water. And clean up when you just peed on my door. Really? This is hard enough. I don’t need to be doing that.”

Since the city started cleaning up the streets, business has increased by 20 percent. She now welcomes the giant tents — two of which are within a block of her business — if people eventually end up in permanent housing.

She’s also trying to help. Her coffee roasting lab offers job training and works with a school exclusively for homeless students.

“But if it gets as bad as it was again, I’d probably move,” she said.

John Long did relocate his Halcyon coffee bar and lounge in October to San Marcos, a town north of San Diego. Three years ago, the hip Austin-based chain opened to much fanfare as a sign of downtown’s gentrification, with floor-to-ceiling windows and a patio that looked onto a new park.

But espresso-drinking customers ended up with a view of people sleeping on the grass.

“One had to hope that with that much investments going into the area downtown, the city would keep the sidewalk clean — especially the park — but that didn’t happen,” Long said.

Long kept his lease and may someday reopen a business there. First, though, “There needs to be a dramatic change and action.”

___

Father Joe’s Villages is working on a $531 million plan to take about 2,700 people off the streets through new construction or by refurbishing motels over the next five years. Federal, state and local funds will cover most of the cost, but the charity still must raise $120 million.

“That’s truly what we need just to make a dent,” said Deacon Jim Vargas, the group’s president.

The mayor has earmarked more than $80 million to reduce homelessness over the next three years. The plan includes incentives for landlords and $30 million for developers to create 300 affordable units. The goal is for 65 percent of tent occupants to be moved into housing.

“Ultimately the goal is to put everyone in a home who wants to be,” Faulconer told The Associated Press. “We need to get people off the streets now and then move forward on constructing units.”

But the temporary solution is expensive. At a cost of $1,700 per person per month, $6.5 million will cover seven months, but the tents may need to remain open for up to two years, depending on the housing market, according to the San Diego Housing Commission’s head, Rick Gentry.

Meanwhile, San Diego County has spent more than $4 million to cope with the hepatitis outbreak. Public health nurses carting coolers of the vaccine have administered more than 100,000 shots, including outside restrooms and libraries and under freeway overpasses.

It didn’t have to come to this, said Michael McConnell, a retired businessman-turned-activist who prods the city to stop arresting the homeless.

“The slogan ‘America’s Finest City’ is being tarnished day by day because the city has been turning a blind eye to its most vulnerable,” McConnell said, as crews sprayed a bleach solution along 17th Street in September after people moved bags, bicycles and overflowing grocery carts.

In 2005 and in 2015, the grand jury recommended the city provide more public restrooms to its homeless population. But city officials feared they would attract drug dealers. They also balked at the $250,000 estimated installation cost and the hundreds of thousands of dollars believed needed to operate them.

Then hepatitis A made it everyone’s problem.

With more than 560 cases and more than 360 people hospitalized, doctors recommended vaccinations to anyone who regularly goes downtown. Members of one fire crew were inoculated after stomping through human feces.

___

At Perkins Elementary School, staffers have found excrement and urine outside classrooms before the school opened for the day, and some worry the hepatitis virus may be brought into the school on shoes. Perkins has a playground with a panoramic view of sleek high-rises and the shiny dome of the city’s new central library; it also has a student body that is more than a quarter homeless, up from 4 percent three years ago.

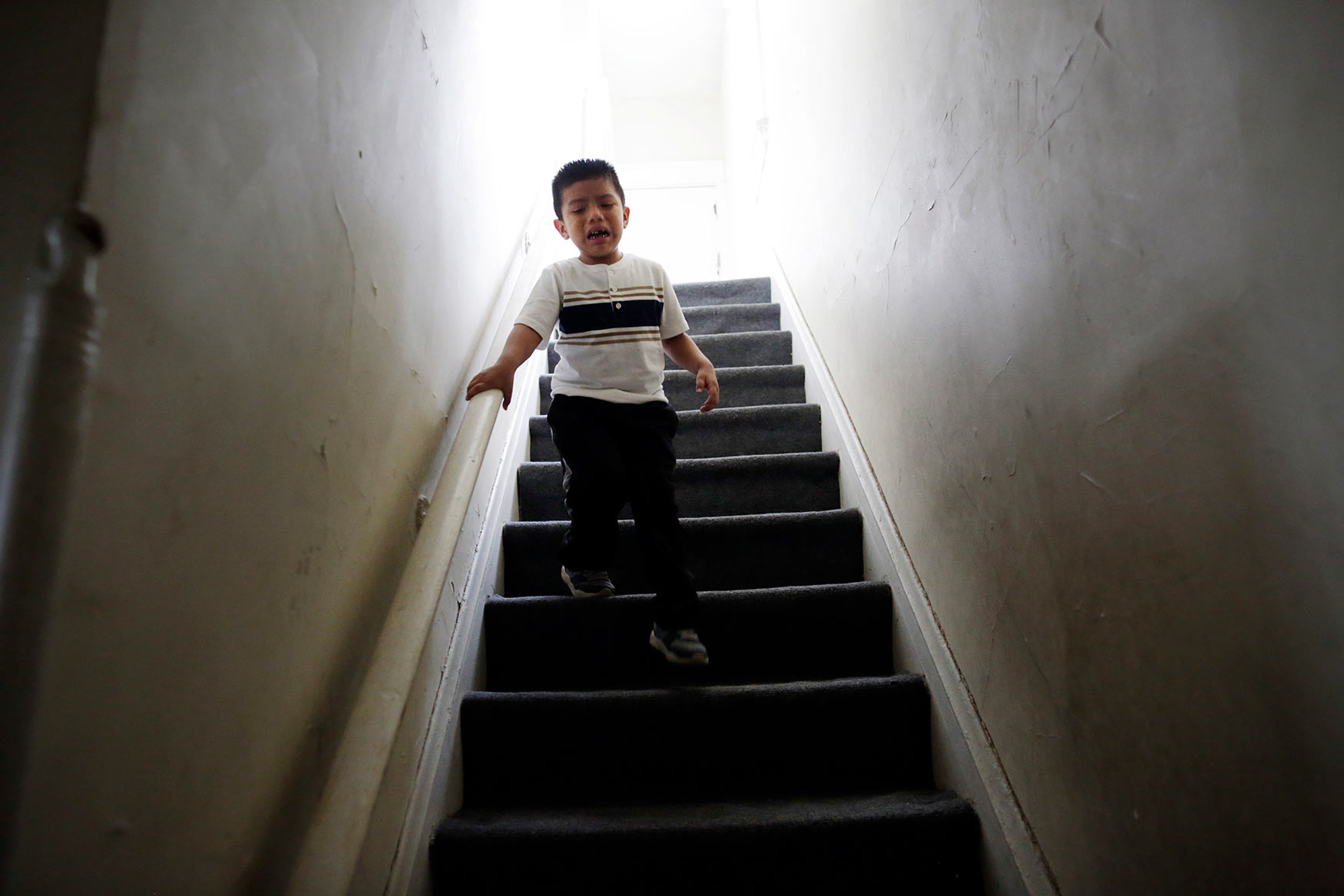

Homelessness takes a particular toll on the young. Fernando Hernandez, Perkins’ principal, said many of the homeless students are far below grade levels. Some have not attended school in years.

“We have first graders who get out of bed and get to school on their own,” Hernandez said. “Some come to school after sleeping on a floor and don’t sleep well. That may be why they are not learning. So we have to recalibrate our expectations.”

Shawnni Wade was a straight-A student as a third grader before her family’s troubles escalated. In all the upheaval, she left the school; now, she’s returned as a seventh grader.

“It’s weird to be back,” said the girl with bright green eyes and a sly smile.

But then, little about this 12-year-old girl’s life has been normal.

Christine Wade’s ex-husband’s drug addiction got them booted from apartments and then a shelter. After they divorced, he let Wade care for his two daughters, whom she had raised for eight years. She moved the six children to a residential hotel, where she paid $1,200 a month for a kitchenette with two queen beds.

But Wade, who is in poor health, often called in sick. She lost her job cleaning hospital rooms.

A month later, she discovered she was pregnant, despite birth control. A doctor talked to her about abortion. “I didn’t have the heart to do that,” she said.

Without her income, she lost the kitchenette last spring.

“There’s so little help for a big family,” Wade said.

She could find space only in a rat-infested shelter, where the family lived before landing in the Balboa Park campground. As the sun set on their second night there, Shawnni — oblivious to nearby freeway traffic — looked to the sky and said she liked camping. Wade smiled.

Then, a few weeks ago, Wade fell ill again and was hospitalized. She could not return to the campground in her condition, so the family moved into yet another shelter.

A caseworker is now helping her find a home. She hopes to have one before next month, when she expects to give birth to a son.

Text from the AP news story, San Diego’s sunny identity threatened by homeless crisis, by Julie Watson.

Follow AP’s complete coverage of the West Coast homeless crisis here: https://apnews.com/tag/HomelessCrisis

Photos by Gregory Bull

Visual artist and Journalist