North Koreans in Japan loyal to roots amid discrimination

The children, gathered in rows on a school field in Tokyo, crouch and then reach up in unison, waving red, white and blue banners to form a North Korean flag as the school band plays an emotional rendition of a song for their “motherland.”

They are third- and fourth-generation descendants of Koreans, including many who were forcibly taken from their homeland to labor in mines and factories during Japan’s colonization of the Korean Peninsula from 1910 until its 1945 defeat in World War II.

Though many have become citizens of Japan or South Korea, the students’ families remain loyal to their heritage, choosing to send their children to one of some 60 private schools that favor North Korea, teaching the culture and history.

Despite recent North Korean missile launches, including two that flew over Japan, students and graduates of the schools say they take pride in their community and view it as a haven from the discrimination they face in Japan.

“We do things together, and we help each other,” Ha Yong Na, a 16-year-old mix of giggles and poise, said as she demonstrated her Korean dance moves with a classmate.

About 450,000 ethnic Koreans live in Japan, and several thousand attend such schools.

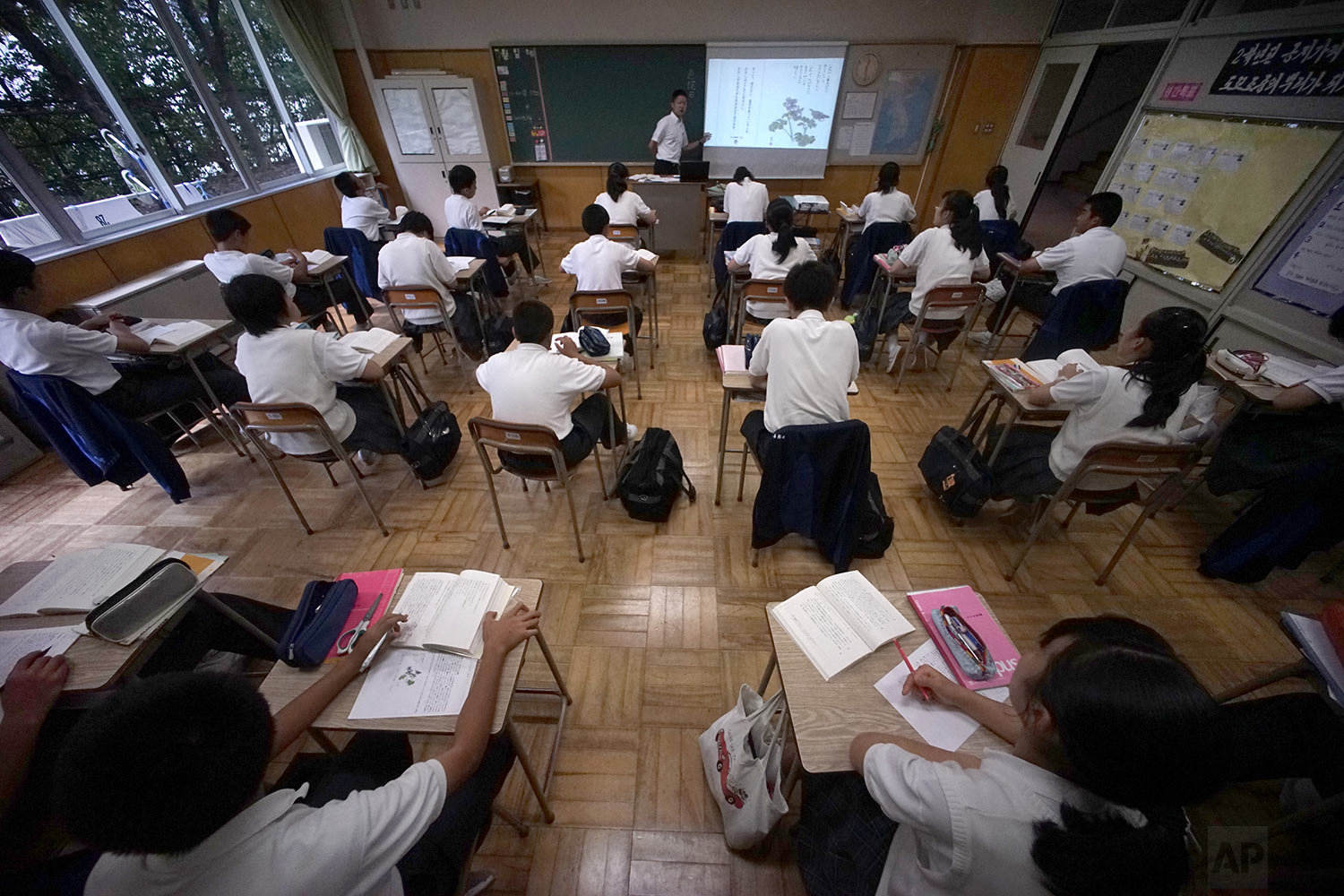

Schools like the North Korean Junior and Senior High School in Tokyo underline a deep divide in a country often portrayed as homogenous. North Korea’s missile launches and nuclear weapons tests have deepened the complexity of the situation.

Ha and her classmates said they cherish their shared heritage and friendships and are happy they don’t have to worry about being picked on for not being Japanese.

“We want graduates of our school to go out into Japanese society, and the world, with pride, as Koreans in Japan, and be able to confidently express themselves,” said Kim Seng Fa, a graduate, teacher and academic affairs director at the 7-decade-old school.

___

In the U.S., being born there makes one an American. In Japan, citizenship must be acquired for immigrants through a government system. Some have complained the process forces people to give up their loyalties to the cultures of their origin.

Many Koreans seek to avoid hassles by taking on Japanese names and blending in. But others like Myoung-joo Boo, a 45-year-old actor, prefer to embrace their ethnic heritage, although he stresses he never tries to get into an argument on cultural pride.

“People who don’t like Koreans don’t have to come near me. And I will live with those who don’t care about such things,” said Boo, a graduate of the North Korean schools.

“In America, people who may have been historically forcibly brought in see themselves as American. But for Koreans, I am born in Japan, but I see myself as Korean,” Boo said.

The schools, founded by the first generation of Koreans in Japan, are privately run and financed by tuition and donations. The graduates and students are fighting several court battles to get the schools recognized as private schools to win the same government subsidies.

The rulings have varied depending on the courts, and the fight is expected to eventually go all the way to the Supreme Court. None of the schools now get such subsidies. Attendance has been shrinking with each generation because of Japan’s overall declining birthrate, and more people choose to assimilate into Japanese society or take South Korean citizenship.

___

One of the worst atrocities against Koreans in Japan came after the Sept. 1, 1923, Great Kanto Earthquake, when thousands were lynched by vigilante mobs and police after false rumors spread that they were poisoning wells.

Today, the antagonisms are less violent, but they remain. Koreans have been traditionally shunned by some mainstream employers. That’s changing, partly because Japanese companies are becoming more global, and employment from multinationals is increasingly available. In the past, the stereotype jobs have been in restaurants and pachinko parlors, and in entertainment.

This year, Tokyo Gov. Yuriko Koike declined to send a customary annual eulogy message to the Korean victims of the 1923 earthquake, which left more than 140,000 people dead or missing in Tokyo and surrounding areas, angering civil rights advocates. She gave no reason, but Koike has won support from nationalist-leaning factions that question accounts of atrocities committed against Koreans and other Asians before and during World War II.

Extremist groups sometimes take to Tokyo streets, waving militarist rising-sun flags and chanting anti-Korean slogans.

Online hate speech remains rampant, with trolls stalking people known to have Korean ancestry, such as actress Kiko Mizuhara. Students of North Korean schools are sometimes harassed on commuter trains, and some have had their clothing slashed with knives.

Hwaji Shin, a sociology professor at the University of San Francisco, who grew up as a third-generation Korean in Japan, believes the harassment has worsened, becoming more systematic and threatening as worries mount over North Korea’s missile and nuclear programs.

Resentment toward immigrant communities and other minorities, apparent in many countries, also reflects insecurities over globalization and widening inequality, Shin said.

“When people are increasingly competing over a smaller pie and when someone whispers in your ear, those are the people who are taking the slice of pie away from you. It is very easy to harbor hatred against that group,” she said.

The myth persists that Japan has no problem with discrimination, and the country’s mainstream media rarely mention such issues, Shin said.

As in most immigrant experiences, successive generations of Koreans in Japan, including those at the North Korean schools, speak Japanese at home. Like their Japanese peers, they enjoy Japanese pop music and American rock, and watch local and American TV shows and Hollywood movies.

Yet Yeong-I Park, a 42-year-old filmmaker who attended North Korean schools from kindergarten through college, still considers himself “a foreigner.”

He is married to a Korean born in Japan and his children attend North Korean schools. He has visited North Korea 17 times, and says the country is changing.

Like others of his background, he empathizes with North Korea’s historical view that it is their own country that suffered a brutal war of invasion by the U.S. — a narrative contrary to the Western view that North Korea was the aggressor in the 1950-53 Korean War.

Park views North Koreans as misunderstood victims.

“I feel news about North Korea is really exaggerated, especially in Japan,” he said. “They depict it as though it’s hell on Earth.”

Kum Son Gyun, 17, a student at a North Korean school, visited North Korea on a school trip this year and found the place anything but hellish.

“It was a fantastic place,” said Kum, whose father works as an editor of a publication for the North Korean community in Japan. “They had cows.”

When asked about the recent North Korean news dominating coverage in Japan — the missile and nuclear threat — his eyes started to brim with tears.

“I want to believe my country is right, and I have believed in my country since I was a child, and that isn’t going to waver,” he said. “I believe my country is right.”

Text from the AP news story, North Koreans in Japan loyal to roots amid discrimination, by Yuri Kageyama.

Photos by Eugene Hoshiko, Shuji Kajiyama, Shizuo Kambayashi and Yuri Kageyama

Visual artist and Journalist