Bangladesh failing to spare millions from arsenic poisoning

For more than two decades, Nasima Begum and her family have been drawing water from a well painted red to warn Bangladeshi villagers that it's tainted by arsenic. They know they're slowly poisoning themselves.

"We use this water for washing, bathing and drinking," she said. There simply is no other option. Taking loans from neighbors to care for her ailing husband and four children, Begum, 45, has nothing left to invest toward digging a new well that goes deeper to reach safe water.

But she shouldn't have to, according to a government program aimed at establishing safe tube wells in poor villages.

An estimated 20 million people in Bangladesh are still being poisoned by arsenic-tainted water — a number that has remained unchanged from 10 years ago despite years of action to dig new wells at safer depths, according to a new report released Wednesday by Human Rights Watch.

The New York-based rights group blames nepotism and neglect by Bangladeshi officials, saying they're deliberately having new wells dug in areas convenient for friends, family members and political supporters and allies, rather than in places where arsenic contamination is highest or large numbers of poor villagers are being exposed.

Government officials refused requests by The Associated Press for comment on the findings.

Human Rights Watch based its report on a survey of about 125,000 government wells dug from 2006 to 2012 specifically to give villagers safer options, after an earlier survey of 5 million wells found millions exposed to water that exceeded Bangladesh's arsenic contamination limit of 50 parts per billion. Bangladesh's limit, which is the same as in neighboring India, is far higher than the World Health Organization's recommended limit of 10 ppb.

"What we found was basically poor governance," said Human Rights Watch senior researcher Richard Pearshouse, who authored the report. "There is no technical problem that can't be solved if the political will is there. But what we see is that the government is using many of its valuable resources in areas where there is no need for deep tube wells from the government."

A tube well consists of a long pipe sunk deep into the earth, with a hand pump attached at the top. As surface waters including rivers and lakes became polluted with sewage, industrial effluents and agricultural runoff, millions of tube wells were dug by the government and international aid groups.

But they inadvertently tapped into arsenic, a naturally occurring and toxic element found in the soil and groundwater of some areas of the world, including vast delta regions like Bangladesh and eastern India.

Arsenic also kills about 45,000 Bangladeshis every year, and is known to be in the groundwater of at least 30 countries, including the U.S., Canada and China.

Scientists first discovered arsenic in Bangladesh's groundwater in 1993, sounding alarm bells worldwide about a massive public health crisis pouring from the millions of hand-cranked tube wells tapping water from underground.

The government took action and began testing many of the wells, painting them green if they were safe, or red if unsafe. International aid groups, including the World Bank and UNICEF, also invested money to help the government dig more wells at safer depths.

For years, there was a perception that the problem had been solved. But scientists studying arsenic-tainted tube wells in Bangladesh began noticing a pattern in where the wells were placed.

"We had found that the deep wells the government had installed were clustered, with some villages being very much privileged and others not at all," said geochemist Alexander Van Geen from Columbia University in New York. "We sensed there might be some elite capture of a public good."

Human Rights Watch interviewed 134 people for its report, from villagers at risk to government engineers and officials, some of whom tacitly acknowledged that officials were ignoring the science of which areas were high risk.

The problem is partly rooted in the government's own rules for a program to supply water to rural areas from 2010 to 2015. Those rules say that the poorest and neediest communities should be given priority, but also that members of the national parliament should decide where to allocate 50 percent of those placements.

"There is widespread and systematic diversion of government tube wells," said Pearshouse, the report's author. "These people are not putting them in the right places."

Compounding the problem, there are also wells presumed to be safe that are in fact not safe at all. Around 5 percent of the government's wells turn out to be contaminated above 50 pbb. They might have just been poorly installed, or perhaps a leak has developed in the pipe. Or it may just simply have hit a rare, deep deposit of arsenic.

That's less of a risk than the typical contamination of private wells, which are usually shallow. Experts estimate up to 20 percent are tainted.

Human Rights Watch found that some wells set up by the World Bank and UNICEF were contaminated. Out of 20,000 wells dug from 2007 to 2012 by UNICEF, 1,700 were unsafe. The U.N. charity's chief of water and sanitation in Dhaka said the wells had either been improved or replaced by September. "The problem has been fixed," Hrachya Sargsyan told the AP.

Meanwhile, the World Bank has said that it does not know whether any of the 13,000 wells it supported from 2007 to 2012 were contaminated, but that it will check, according to the report.

Experts estimate that some 20 percent of Bangladesh's 10 million tube wells, most of which are private and shallow, are likely to be contaminated.

Wells that go to depths of about 150 meters (164 yards) or deeper are usually considered safe, but even that is not certain. Scientists say the only way to be sure is to test every well. The government's last testing survey was conducted 10 years ago, and scientists say it's time for another.

But digging deeper wells is expensive. A shallow well can be dug for about $60, while a well dug to 150 meters can run up to $900.

Many people in Bangladesh, an impoverished South Asian country, simply don't have the means.

"We are poor people," said Hazrat Ali, a farmer who has not found safe water despite setting up three tube wells. "There are no rivers and canals close by. From where shall we collect water? For this reason we drink this arsenic mixed water."

Text from the AP news story, Bangladesh failing to spare millions from arsenic poisoning, by Katy Daigle and Julhas Alam.

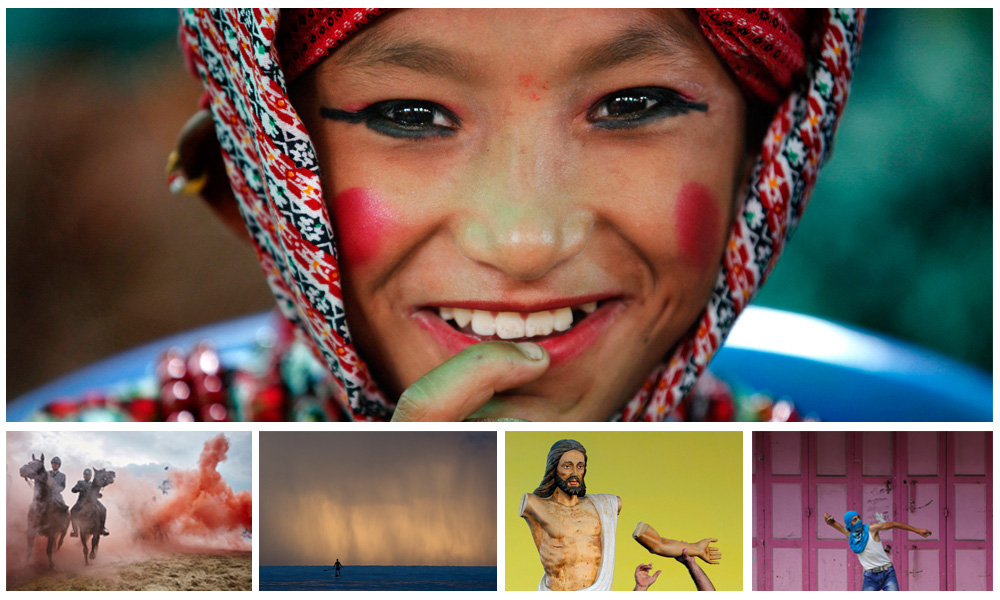

See these photos on APImages.com

Follow A.M. Ahad | Twitter | Instagram

Spotlight is the blog of AP Images, the world’s largest collection of historical and contemporary photos. AP Images provides instant access to AP’s iconic photos and adds new content every minute of every day from every corner of the world, making it an essential source of photos and graphics for professional image buyers and commercial customers. Whether your needs are for editorial, commercial, or personal use, AP Images has the content and the expert sales team to fulfill your image requirements. Visit apimages.com to learn more.

Written content on this site is not created by the editorial department of AP, unless otherwise noted.

AP Images on Twitter | AP Images on Facebook | AP Images on Instagram