El Salvador violence

Word on the street is that only the girlfriends of gang members are allowed to be redheads or blondes. So in this violent place, women are scurrying to salons to give up their blond hair and highlights, to dye it all black — not out of fashion sense, but out of fear.

"They also say you can't wear yellow or red clothing," said Claudia Castellanos, a beautician at an upscale salon. "Can you believe it? They've already attacked a woman on a bus for wearing yellow."

There's no evidence the rumors are true. The gangs, sophisticated criminal organizations, even issued a statement to deny the hair-color decree.

But with violence in El Salvador reaching levels rivaling those of the civil war that ended more than two decades ago, few are willing to take risks.

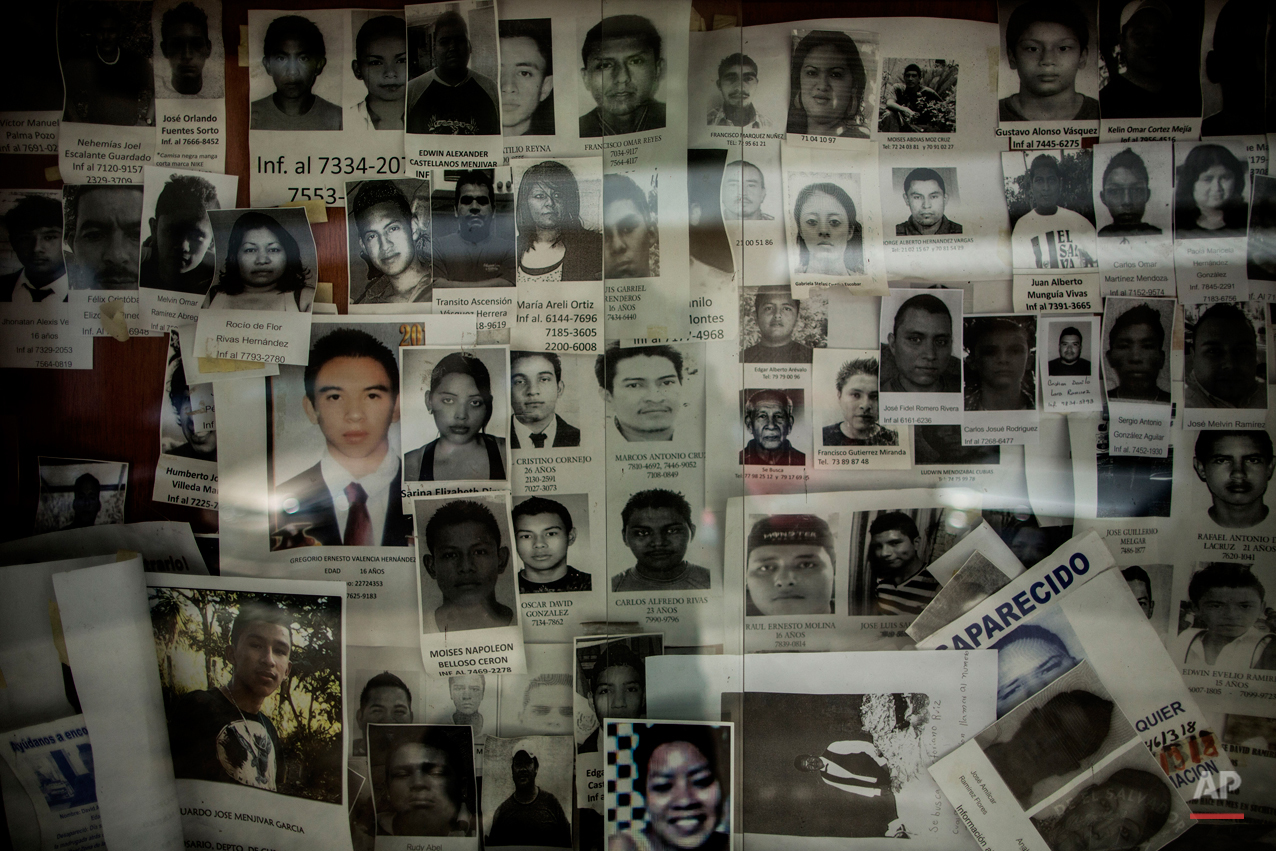

El Salvador has just experienced one of its most violent months since the end of the civil war in 1992, with 635 homicides reported in May for the country of just over 6 million people. June is on track to break that mark, with the latest bloodshed coming Sunday when suspected gang members killed two soldiers guarding a bus terminal in the capital.

Fear is pervasive across San Salvador. As daylight fades, stores close early and streets empty. At night, roadblocks go up to thwart possible grenade attacks on police stations, where officers sleep rather than risk being attacked while riding buses home.

Taxi drivers memorize signals to give gang lookouts who guard neighborhoods, flashing codes with their high beams and rolling down their windows to make themselves visible.

Castellanos counts the number of women who've come to her salon recently seeking to color their hair dark: One, two, three, four ...

"You don't wait for clarifications," said Maria Jose Estrada, a former blonde who lives on the outskirts of San Salvador. "These people are crazy and they will kill you."

Police officials and others blame the worsening insecurity on the breakdown of a truce made between the gangs and the government in 2013. While the homicide rate plunged, critics say the truce gave the gangs time to strengthen, train and acquire heavier arms than they had in the past.

Jailed gang leaders were moved from maximum-security prisons to more lax facilities where they were able to run their criminal operations remotely.

But in January, the 6-month-old government of President Salvador Sanchez Ceren publicly rejected any truce and launched an aggressive crackdown, putting gang leaders back in maximum-security cells. The change has meant the streets now are controlled by younger, better-armed criminals who are willing to be reckless.

"You take away the mature leadership, and you get a structure that is made up of younger, fanatical people who want to make a name for themselves," said Raul Mijango, a former guerrilla and a facilitator of the truce. "They want war."

The police say they are ready for battle.

"Things have to get worse before they get better," said a police official, who agreed to comment only if not quoted by name for fear of reprisals. "When I see one (gang member) on the street, I'm going to shoot him before he shoots me."

Police say the crackdown on gang strongholds in the cities has caused members to flee to surrounding rural areas, bringing violence with them.

On a warm, muggy May night in Olocuitla, a town about 20 miles (30 kilometers) south of San Salvador, the bodies of two teens were found in a steep gully after a shootout with police near an old cattle stable, which gang members had turned into a shooting range. One of the dead was the leader of the cell, a 16-year-old who had a grenade in his hand.

Such evidence of crime's spread has rural residents taking new precautions.

Carlos Treminio, a street vendor who lives on the north edge of the capital, now accompanies his teenage son and daughter on their walk to school rather than leave them vulnerable to gang recruiters.

"These jerks lurk around the schools and offer everything to join the gang. If you refuse, they kill you," Treminio said. "I will do everything to protect my children."

Howard Cotto, assistant national police chief and a former guerrilla commander, said the gangs will not find the sort of rural support enjoyed by rebels in the 1980s because they have no ideology.

"They are much more vulnerable," he said.

But, he believes, nothing will change unless the country addresses problems of poverty and a lack of opportunity for young people. The government has arrested 12,000 gang members in the last year with little to show for it, he said.

"We can go in and arrest 50 gang members and 50 more will take their places," Cotto said. "With just arrests, we won't accomplish anything."

Mijango, who helped negotiate the last truce, sees negotiation as the path to avoid the sort of bloodshed the country saw when his Farabundo Marti National Liberation was fighting conservative governments in the 1980s.

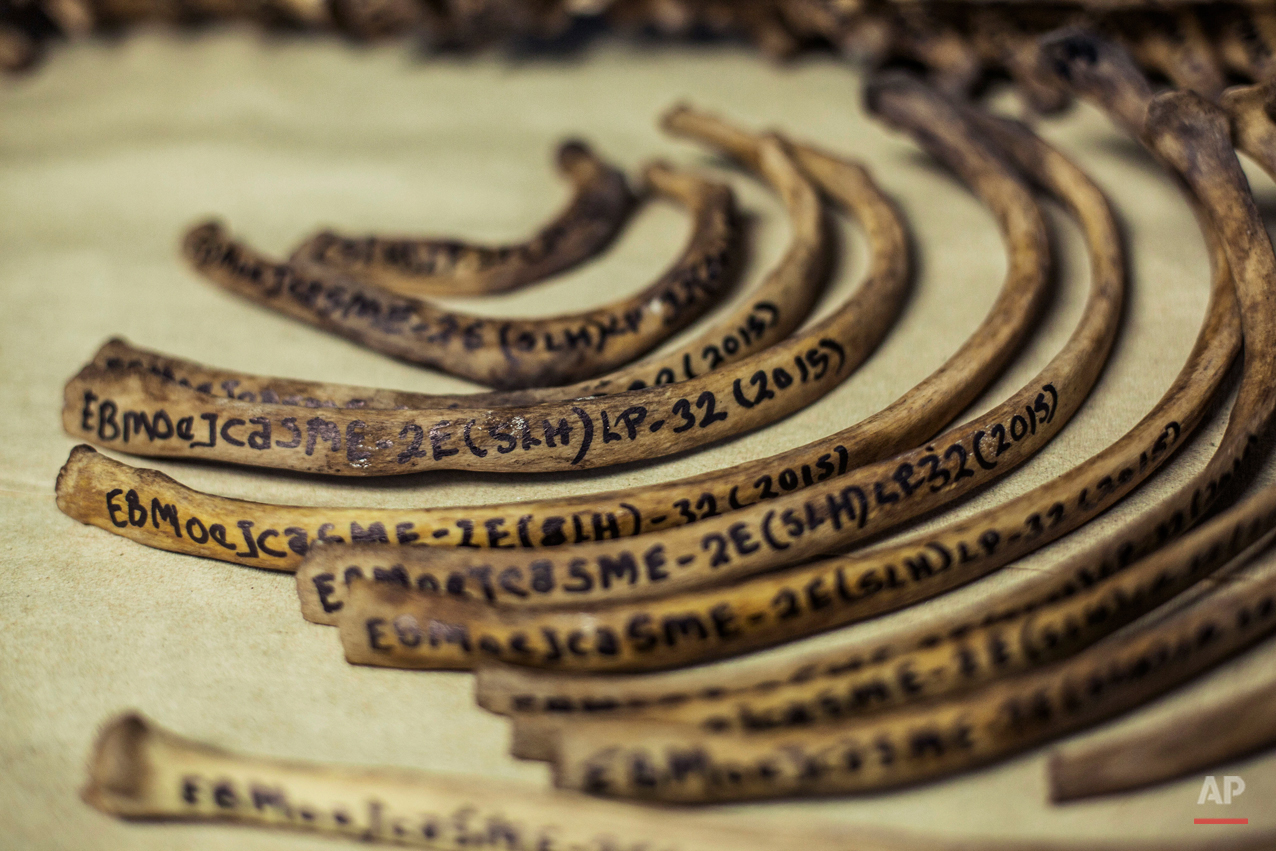

Now the former rebel movement is the governing party and it is the gangs who control territories where 90 percent of El Salvador's people live, noted Miguel Fortin Magana, the chief forensics officer for the country's Supreme Court.

"This is like a virus that has spread throughout the country," he said.

Text from the AP news story, Bloodshed in El Salvador reaching levels of 1980s civil war, by Alberto Arce.

Spotlight is the blog of AP Images, the world’s largest collection of historical and contemporary photos. AP Images provides instant access to AP’s iconic photos and adds new content every minute of every day from every corner of the world, making it an essential source of photos and graphics for professional image buyers and commercial customers. Whether your needs are for editorial, commercial, or personal use, AP Images has the content and the expert sales team to fulfill your image requirements. Visit apimages.com to learn more.

Written content on this site is not created by the editorial department of AP, unless otherwise noted.

AP Images on Twitter | AP Images on Facebook | AP Images on Instagram

Visual artist and Journalist