Dennis Lee Royle 1923-1971: AP Photographer

In his nearly 30-year career with AP, photographer Dennis Lee Royle (1923-1971) covered news in Europe, Africa and Asia.

On May 20, 1971, while covering naval exercises conducted by the North Atlantic Treaty Organization, the helicopter he was in crashed over the English Channel. Royle was killed in the crash as were Edward Beer of the British Press Association and Guy Blanchard who was working for the American Broadcasting Company.

“It is a tragic irony that Dennis, who had been in so many dangerous spots for The Associated Press, such as the Hungarian revolution, wars in the Middle East and in India, lost his life in such an accident – but still in the pursuit of the news, as were his colleagues who died with him,” said Wes Gallagher, AP's president and general manager.

Associated Press photographer Dennis Lee Royle is shown in Johannesburg, Feb. 14, 1963. (AP Photo)

Born in England, Royle joined the Royal Air Force (RAF) in 1939 and served as a flight engineer on board the aircraft that he serviced. He was released from the RAF in 1943 after being injured in a crash landing. Royle began his first assignment at the AP on July 12, 1943 as a photo librarian in the London bureau. He progressed to caption writer and night photo editor, all the while learning the art and science of photography from veteran AP photographers Eddie Worth and Leslie Priest.

A vital if unspectacular link in the maintenance of the Royal Air Force's contribution to the airlift into blockaded Berlin is "Operation Plumber." This is the R.A.F.'s name for the major servicing unit of transport command at Honington, Suffolk, where a fleet of six Dakotas is kept busy flying unserviceable aircraft parts back from Germany and taking out immediate replacements. Here a giant wheel for a York aircraft, grounded at Wunstorf, Germany, Nov 24, 1948 is trundled out to a waiting Dakota of "Operation Plumber." (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Holland's Fanny Blankers-Koen, left, waves goodbye to members of the Dutch team from her train at Liverpool Street Station, London, Aug. 9, 1948. Blankers-Koen won four Olympic gold medals. (AP Photo/Dennis-Lee Royle)

The British organizing committees for the Summer Olympic Games have disclosed that revolutionary equipment for track and field events is to be used. The apparatus used will set new standards in athletic measuring equipment. In this image H. Rottenburg, British inventor of starting blocks for track and field sprint events, demonstrates his blocks at Cambridge, United Kingdom, on April 7, 1948. He is using a stance that he perfected together with Jaako Mikolo from Harvard University, U.S.A., who was in this country as Olympic coach for the 1939 team at summer school, Loughborough. The blocks can be adjusted to any angle and distance from the ground. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Seen on their arrival at London airport from Africa, July 8, 1951, are from left to right, film stars Lauren Bacall, her husband Humphrey Bogart and Katherine Hepburn. Bogart and Hepburn have been filming C.S. Forester's "African Queen." (AP Photo/Dennis-Lee Royle)

Actress Elizabeth Taylor is greeted by fiance Michael Wilding on her arrival at London Airport, London, Feb. 19, 1952. The couple are due to wed in London on Feb. 20. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Former British Prime Minister Winston Churchill gives a congratulatory pat to his horse Colonist II after it had won the Winston Churchill Stakes race at Hurst Park race-course , Surrey, on May 14, 1951. (AP Photo/Dennis-Lee Royle)

In December 1951, the world’s attention turned to the fate of the Flying Enterprise, a freighter in distress on a voyage from Hamburg to New York. Hit by a storm in late December, passengers and crew were forced to abandon ship, jumping into the cold Atlantic waters, from which they were rescued. Captain Kurt Carlsen and chief mate Kenneth Dancy stayed aboard ship, hoping to guide it to a safe harbor, but on the afternoon of January 10, 1952 as the Flying Enterprise, now listing at 90 degrees and taking water down the stack began to sink, both Dancy and Carlsen jumped into the sea from off the stack and were taken aboard the Turmoil.

The AP was there, with three staffers aboard the tug Englishman, from which they reported the sinking of the Enterprise and the final expolits of Captain Carlsen who refused to abandon ship until the last possible moment. Royle boarded the Englishman with three cameras, a Speed Graphic with a 5 1/4 inch lens, a 13-inch telephoto on a Graphic, and an 18-inch telephoto on a Graflex. The 13-inch telephoto made the final shots, the other two cameras having been knocked out by bumping agains the bulkheads.

As the Flying Enterprise (top photo) nears its end, Alvin Steinkopf (left) and Dennis Royle confer aboard the Associated Press tug Englishman on a detail of coverage. The fate of the Flying Enterprise and its captain captured the headlines for a week.

AP Wirephoto graphic showing the route of the Flying Enterprise.

Associated Press staff photographer Dennis Lee Royle of London, crosses on bosun's chair from the light carrier Vengeance to the destroyer Vanguard, to dine with the First Lord of the Admiralty, in Espichel Bay, south of Lisbon, Portugal, Sept. 1950. (AP Photo)

Bandleader Louis Armstrong is shown at London Airport, May 3, 1956 after arriving from New York. Watching Armstrong is a young unidentified admirer. Armstrong is scheduled to open at the Express Hall in London on May. 4. (AP Photo/Dennis-Lee Royle)

Twenty-seven year old Seretse Khama, heir apparent to the throne of Bechuanaland, pictured on Oct. 18, 1948 with his 24 year old bride, formally Miss Ruth Williams, who worked in a London office. Seretse Khama, who came to London to study law before taking over the reins of state next year leaves alone for home on Thursday, just over two weeks after his wedding. He will either be back for his bride or will send for her, he says, "Whatever happens". (AP Photo/Dennis-Lee Royle)

The British, bowing to pressure from apartheid South Africa, banished Seretse Khama and his wife from Bechuanaland for 5 years. After returning to Bechulanaland in 1956, Khama became active in politics, advocating for independence. Bechuanaland was renamed Botswana upon gaining independence in 1966, with Seretse Khama as the first president.

Evangelist Billy Graham sits in meditation in a jungle clearing a few miles from Ibadan, Western Nigeria, Feb. 1, 1960. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

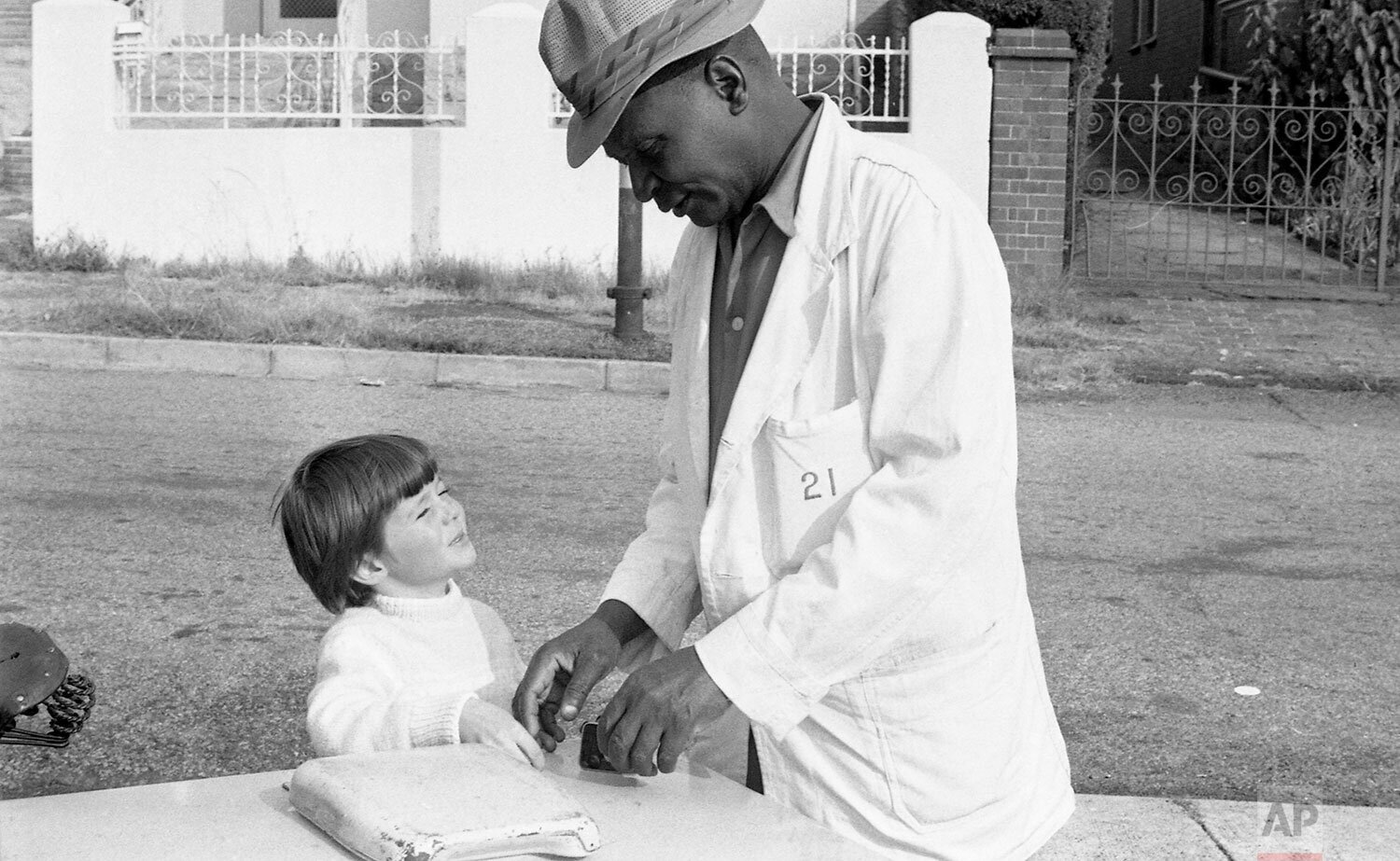

Assigned to Africa in 1961, Royle covered African independence movements, the Congo war, the Biafran war, and the struggle against apartheid in South Africa, from his home base in Johannesburg. In his first four years in Africa he went on 58 long distance assignments on the continent. Royle was a talented writer whose bylined stories often accompanied his photos. When the South African government refused to renew his visa in 1967 he re-located to Salisbury, Rhodesia, now known as Harare, Zimbabwe, until authorities there proclaimed him a prohibited immigrant. His photos of starving children in Biafra during the Nigerian Civil War were credited with prompting relief efforts.

Britain's Prince Philip, the Duke of Edinburgh, hands the Instruments of Independence to Kenya's Prime Minister Jomo Kenyatta during the independence ceremony at Uhuru Stadium, Nairobi, Dec. 12, 1963. The ceremony ended 68 years of British rule in Kenya. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

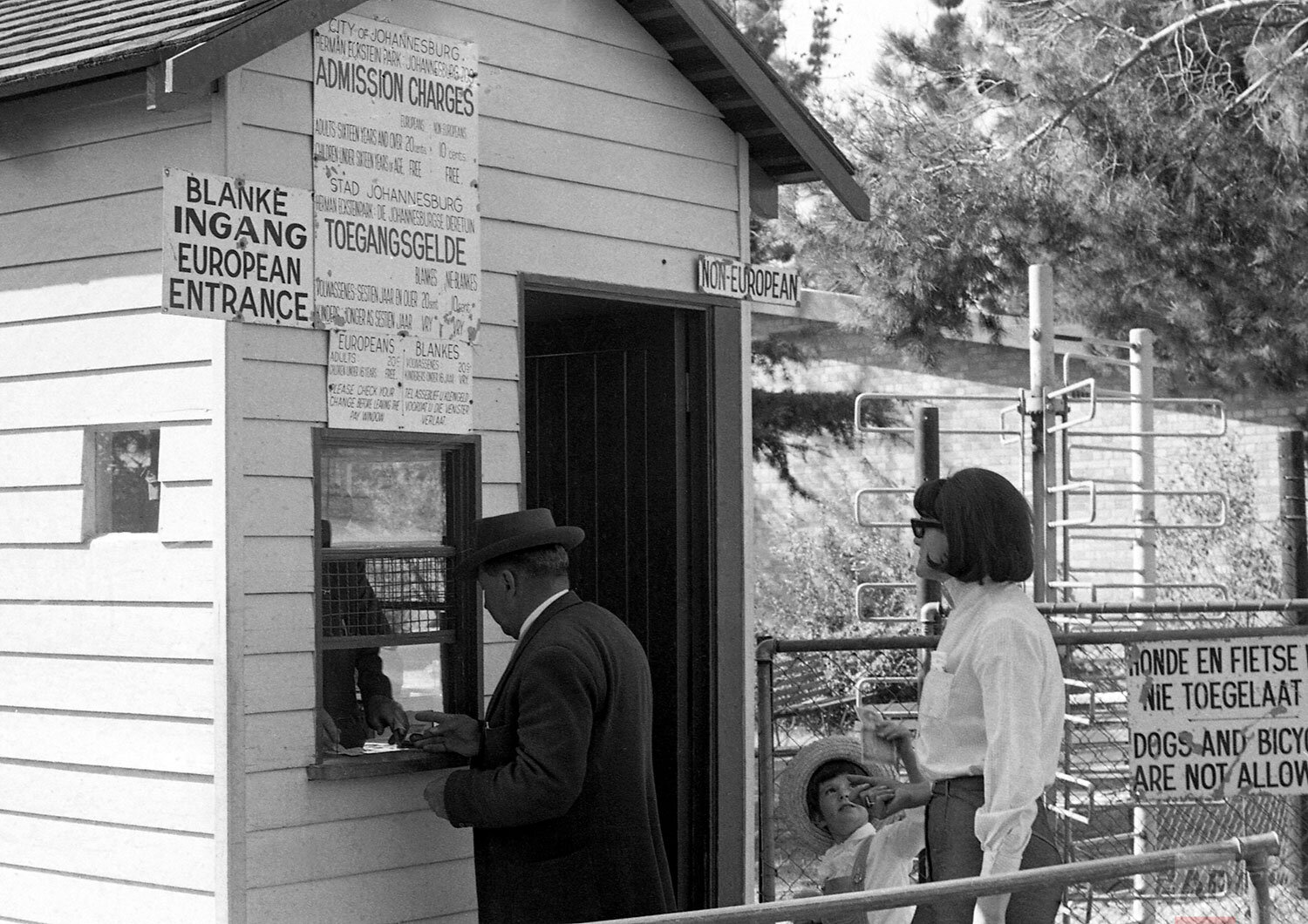

Royle’s work in South Africa captured both the inhumanity and absurdity of the apartheid regime. Many of the photos in this gallery focus on the ubiquitous labels that mark public spaces. In his book “House of Bondage,” the South African photographer Ernest Cole writes: “The infectious spread of apartheid into the smallest detail of daily living has made South Africa a land of signs. They are everywhere, written in English or Afrikaans… But always their purpose is the same: to spell out the almost total separation of facilities on the basis of race.”

African women join in a demonstration in South Africa, Aug. 16, 1962, demanding the release of Nelson Mandela, former secretary of the banned African National Congress, who appeared in court on a charge of incitement. The women, together with Winnie Mandela chanted "down with Verwoerd on the steps of the Johannesburg City Hall. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Placards referring to apartheid are held up by African demonstrators who greeted two delegates of the United Nations committee on South West Africa, on their arrival at Windhoek, May 9, 1962. The delegates are on a fact-finding mission to investigate allegations that racial oppression exists in the mandated territory under the supervision of South Africa. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Led by the reverend Leslie Stradling, leaders of Methodist and Congregational churches held a protest rally in the Johannesburg Town Hall, May 20, 1964, to protest against South Africa's ninety-day law which enables police to detain and question suspects for up to 90 days without trial and be held in solitary confinement. Methodist churchman Ian Hughes seen addressing Africans outside the Town Hall. They are not allowed inside under apartheid laws. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Johannesburg housewives fire .22 pistols at a target during one of the weekly "pistol parties" in the capital of jittery white supremacist South Africa, Aug. 30, 1963. These housewives belong to a pistol-packers' club of women aged 25 to 61, all top marksmen. It's all part of South Africa's defense build-up against attacks which the country's leaders say they expect from other African countries. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Sen. Robert F. Kennedy (D-N.Y.), is surrounded by South African students and newsmen as he tours Stellenbosch, near Cape Town, South Africa on June 7, 1966. Kennedy is on a five-day visit to South Africa as the guest of the multiracial National Union of South African students. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Col. Don Davis, United States military attache in Pretoria, South Africa, plays a tune on the piano for his pet cheetah, Sandy, who appears to have a musical ear, on Nov. 12, 1963. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

The Union Jack is hauled down for the last time when Northern Rhodesia became the independent African Republic of Zambia during a ceremony in Lusaka on Oct. 24, 1964. (AP Photo/Dennis-Lee Royle)

Kenneth Kaunda, the President of Zambia, in London for talks with British Prime Minister Harold Wilson, in August 1965. (AP Photo/Dennis-Lee Royle)

Overcoats and blankets keep electors warm as they queue to vote for Basutoland's first internal self-governing parliament, in Maseru, the capital, on April 29, 1965. The British protectoratte enclave in South Africa will eventually become fully independent as the Kingdom of Lesotho. (AP Photo/Royle)

King Sobhuza II of Swaziland is shown, 1966. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Ibo refugees from the breakaway Nigerian state of Biafra carry household goods on their heads as they flee advancing federal Nigerian troops near Owerri, Sept. 1968. Youngster at right carries another child. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Three hungry young Ibo refugees, two carrying pots on their heads, are seen near Owerri, Biafra, Sept. 22, 1968. Owerri, the Ibo heartland town, fell to federal Nigerian forces last week. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

Coffins can be made to order while the customer watches in Lagos, Nigeria, where the kerbside coffin-maker does a brisk trade with cheap caskets built mainly from old packing cases. The craftsman works in the busy city centre, advertising his wares prominently with a large cut-out poster. (AP-Photo/Royle/stf/R.) 12.03.1965

Jubilant Nigerians in the capital city of Lagos cheer as they read of the surrender of the rebel Biafran forces, Jan. 12, 1970. Nigerian leader Maj. Gen. Yakubu Gowon accepted the Biafran surrender and asked all Nigerians to greet the former rebels as brothers. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

England's Geoff Hurst, centre in white, attempts to head the ball during the World Cup Group C match against Romania, in Estadio Jalisco, Guadalajara, Mexico, on June 2, 1970. England defeated Romania by 1-0, the goal was scored by Hurst. (AP Photo/Stf/ Royle)

Catholic people demonstrate with Royal Engineers of the British Army and sit atop their barricades in Cupar Street, Belfast, Northern Ireland on Sept. 10, 1969. (AP Photo/Royle)

Children of Britain's Royal family pose for a family group photo at Windsor Castle on Christmas morning, in 1969, after they had attended divine service at St George's Chapel. With Prince Charles and Princess Anne are, from left to right; James Ogilvy, five year old son of Princess Alexandra and Angus Ogilvy, Lady Sarah Armstrong-Jones, five year old daughter of Princess Margaret and the Earl of Snowdon, seven year old son of the Duke and Duchess of Kent, Lady Helen Windsor, five year old daughter of the Kent's, Prince Andrew (at rear) and Prince Edward, Viscount Linley, Princess Margaret's eight year old son, and Marina Ogilvy, Princess Alexandra's three year old daughter. (AP Photo/Dennis Lee Royle)

A young boy sits on a burnt out car in Belfast, Northern Ireland during disorders in September 1969. (AP Photo/Royle)

Photo editing and text by Francesca Pitaro, AP Corporate Archives.