AP at 175, Part 2: Evolution, 1861-1900

The Associated Press (AP) celebrates its 175th birthday in May 2021. To mark this milestone, the AP Corporate Archives has assembled a concise visual history of the organization, offered here in an eight-part monthly blog, “AP at 175.” This is the second of eight installments.

Valerie S. Komor

Director, AP Corporate Archives

Part 2: Evolution, 1861-1900

When Abraham Lincoln assumed the presidency on March 4, 1861, Lawrence A. Gobright (1816-88) had been a Washington, D.C. journalist for nearly 30 years and the AP’s “chief correspondent” there for six. As we learn in his memoir, Gobright enjoyed remarkably easy access to the president during the Civil War, even calling on him unannounced at the White House to “learn the latest news.” The relationship was useful to both men. During the war, Lincoln needed to reach a broad audience and AP made that possible.

It is likely that Gobright hired a young Harrisburg stenographer, Joseph Ignatius Gilbert (1842-1924), to take down the president’s remarks at the dedication of the Soldiers’ National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Pennsylvania on Nov. 19, 1863, and we know from the president’s secretary, John G. Nicolay, that Lincoln relied on the AP account when making his fair copies on his return to the White House.

The war left its mark on AP governance, as it did on society at large. A group of northern Midwest papers formed the Western Associated Press at a meeting in Indianapolis on Nov. 25, 1862. This body, headquartered in Chicago, ran the AP jointly with New York until 1893. In May 1900, under Chicago Daily News publisher Melville E. Stone, it moved to New York City and incorporated under New York state law as the Associated Press.

“Associated Press Rooms,” 1877. Harper’s New Monthly Magazine, December 1877.

This illustration appeared in “The Metropolitan Newspaper,” an article by William H. Rideing, which offers a wonderfully detailed account of AP internal operations at the time.

“As the dispatches reach the general agency,” Rideing explains, “they are handed to the manager of the manifolding-room, under whose direction copies are multiplied for distribution, the manifolding process enabling one writer to make from twelve to twenty-six copies at a time, by means of a very tough oiled tissue-paper alternated with carbonized paper, and an agate or carnelian point substituted for a pen or pencil.

When a page of manifold is written, the office assistants separate and envelope the copies, which are sent to the city newspapers by messengers. Other copies are handed to agents representing sections of the papers in the North, South, East, and West, who edit them, each agent eliminating whatever will not interest his particular constituency, and adding anything of value that he can obtain from other sources.”

Letter from AP Washington Agent, Lawrence A. Gobright, to Lincoln’s private secretary John G. Nicolay, Dec. 1, 1862. Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress Manuscripts Division.

Gobright writes to Nicolay to arrange for the transfer of two copies of the president’s Second Annual Message to Congress, so that he (Gobright) can telegraph the text to the nation’s newspapers.

AP Washington Agent Lawrence A. Gobright, ca. 1865-1880. Albumen print. Brady-Handy Photograph Collections, Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

In his testimony before the House Committee on Judiciary, on Feb. 5, 1862, Gobright was asked to describe his job at the Associated Press. He replied,

“My business is merely to communicate facts. My instructions do not allow me to make any comments upon the facts which I communicate. My despatches [sic.] are sent to papers of all manner of politics, and the editors say that they are able to make their own comments about the facts which are sent to them. I therefore confine myself to what I consider legitimate news….”

AP Harrisburg correspondent Joseph Ignatius Gilbert, ca. 1860. Courtesy Brenda Molloy-Palley.

Gilbert took down President Abraham Lincoln’s address at Gettysburg, but as he became mesmerized by the flow of words, he caught only part of it. When the president had finished, Gilbert asked to borrow his delivery text, copied it in its entirety and ran to the telegraph office where he sent it to New York.

The National Cemetery at Gettysburg, Brooklyn Daily Eagle, Nov. 20, 1863.

The AP report seems to be unique among newspaper accounts in that it uses the plural “governments” instead of the collective “government” in the phrase “government of the people.” It also adds “and” before “for the people.” In his final changes, Lincoln preferred his original “government” and did not accept the conjunction “and.”

The word “poor,” as in “poor power to add or detract” occurs in both the First and Second drafts of the Address. The three later drafts all have “poor,” so Lincoln certainly liked the word and almost certainly said it. But it does not occur in Gilbert’s text. The Philadelphia Inquirer has “poor attempts,” and while the Chicago Tribune has “poor power,” it botched much of the rest. Gilbert may not have heard “poor” because of the repetition of the consonants “p” and “r”.

Military telegram from AP General Agent Daniel H. Craig to President Abraham Lincoln, March 8, 1864. Abraham Lincoln Papers, Library of Congress Manuscripts Division.

“New York City gives ninety five hundred (9,500) majority for allowing soldiers to vote,” writes Craig to the president, giving him the news that absentee Union soldiers could vote in the forthcoming November 1864 presidential election. Lincoln won 78% of the military's vote and 55% of the popular vote, soundly defeating Union Gen. George B. McClellan.

“The Press on the Field.” Colored wood engraving after Thomas Nast. Harper’s Weekly Magazine, April 30, 1864. APCA.

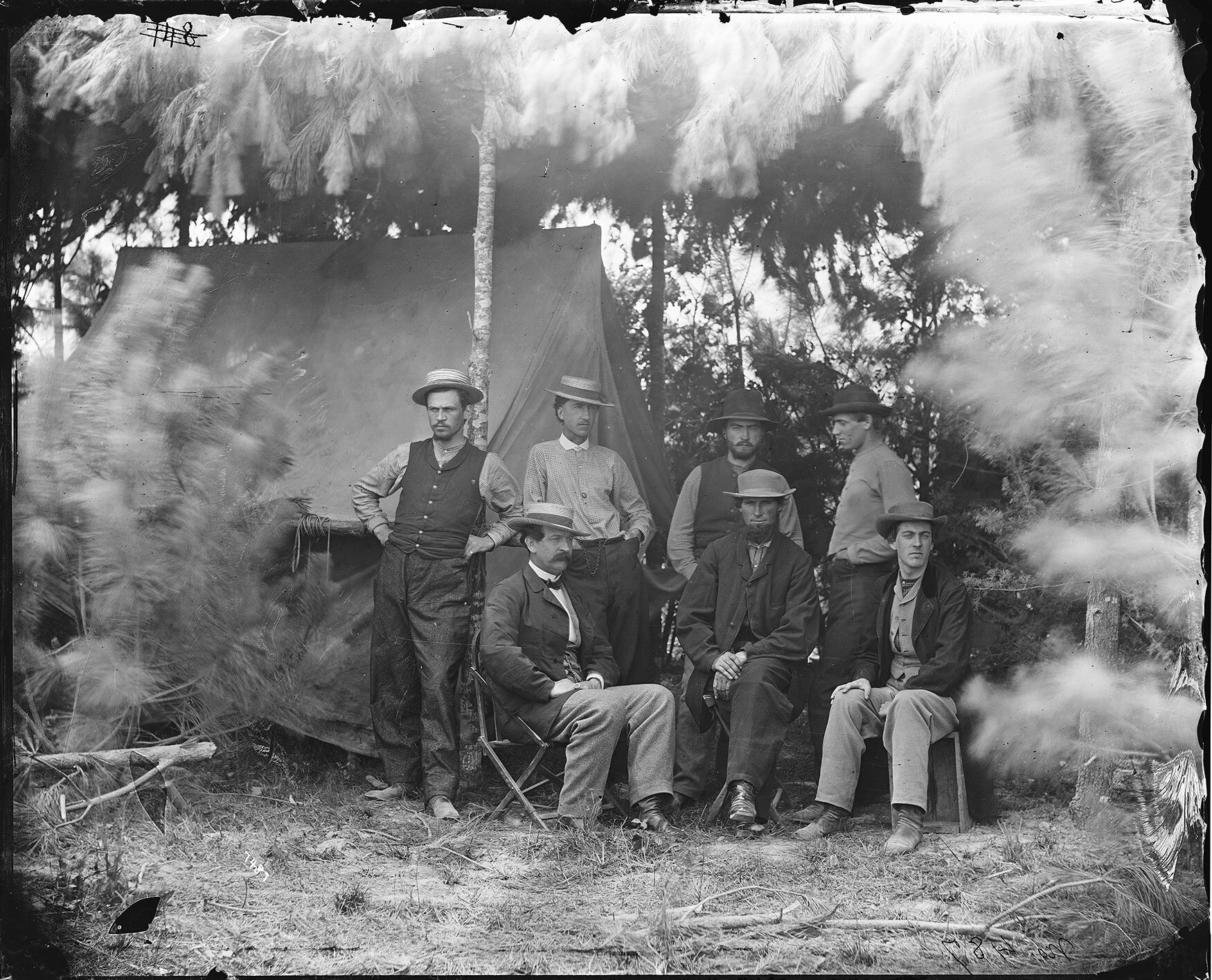

Members of the U.S. Military Telegraph Corps at Petersburg, Va., with Superintendent Thomas Eckert (seated, left). Library of Congress Prints and Photographs Division.

The Corps accompanied every unit into battle to repair severed lines or put up new ones. During the war, it laid 15,389 miles of line. Ingenious methods were used to ensure important messages got through. In June 1862, the corps attached to General George B. McClellan telegraphed enemy movements to Fortress Monroe from a balloon high over the battlefield. “Incessant firing of musketry and artillery was kept up until noon,” recalled the telegrapher, “when I had the extreme pleasure to announce by telegraph from the balloon, that we could see the enemy retreating rapidly toward Richmond.”

“The Atlantic Telegraph Cable,” 1865. Wood engraving after Edwin Forbes, Harper’s Weekly Magazine,

Aug. 12, 1865. APCA.

Occupying the central roundel is the SS Great Eastern, the iron steamship designed by British engineer Isambard Kingdom Brunel and built at Millwall Iron Works on the River Thames in London. It was the largest ship in the world at launching in 1858. The ship achieved instant fame when it completed the almost unimaginable feat, the first successful laying of the Atlantic Cable over the ocean floor, linking Valentia Bay, Ireland to Heart’s Content, Newfoundland on Sept. 7, 1866. The cable was immediately crowned “the eighth wonder of the world.”

Western Associated Press Stock Certificate, 1899. APCA.

On Nov. 25, 1862, “the leading papers of the West,” formed the Western Associated Press (WAP) at a meeting in Indianapolis. They had become unhappy with the quality of dispatches provided by the New York Associated Press but were eager to maintain its cooperative structure. The two organizations were administered by an Executive Committee until 1893, when the AP of Illinois was incorporated. That body moved to New York City in May 1900 and incorporated as the Associated Press.

Associated Press logotype, 1900. APCA.

This is the first logotype created for the modern Associated Press following its incorporation in New York state (May 22, 1900) and its move to New York City. Using the leather belt as a border (which may reference what pony express riders wore), it features the steam engine and the telegraph as examples of technological progress and sets them before the skyline of a thriving metropolis.